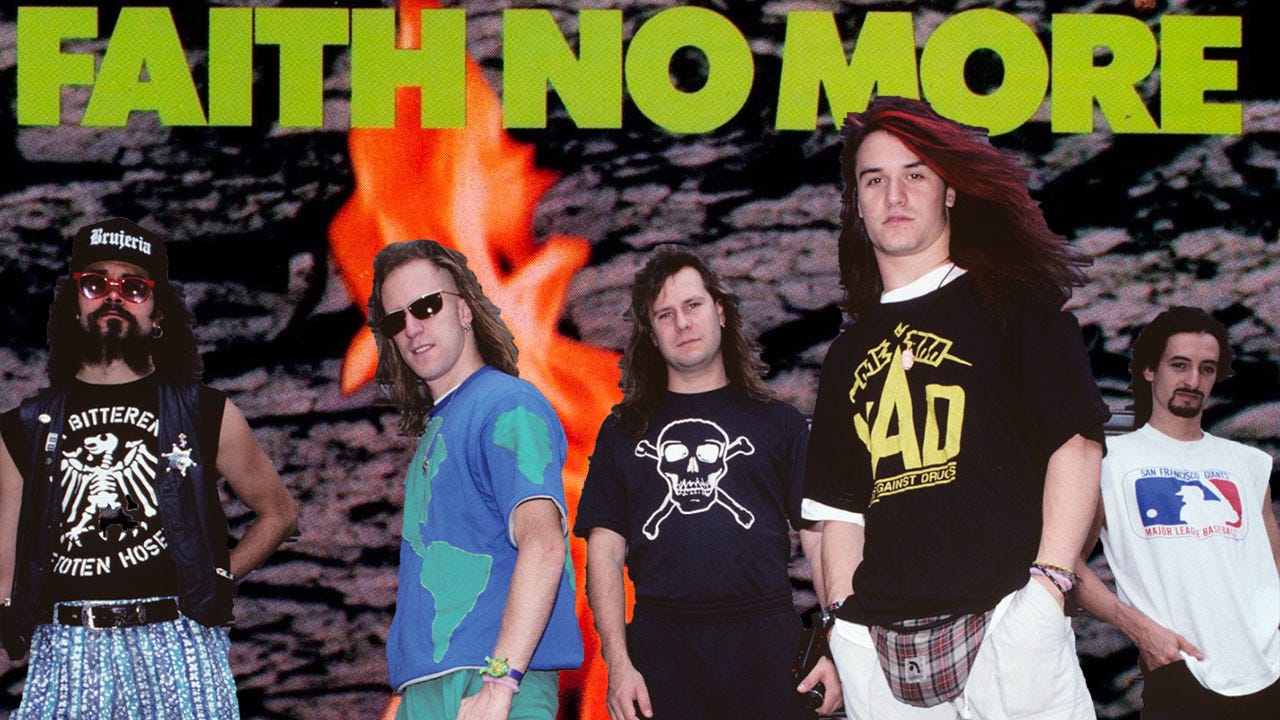

Red Ticket: Faith No More

This weekend in Red Ticket, Robin tries to resurrect her journalism career by interviewing Faith No More after their concert in Moscow. And because this is Robin, she does this by sneaking onto their tour bus.

If you need to catch up, go back and read chapters 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 8-9, 10-11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31.

Chapter 32: Faith No More

by Robin Whetstone

There comes a moment in every person’s life when they realize that their only recourse is to stow away on the tour bus of a moderately famous thrash-rock/hip hop band and hope for the best. For me, that moment came four weeks after the Guardian fired me and six weeks before my big mistake. I was standing in some mid-sized arena in the suburbs of the city, waiting with Betsy and Stu for Faith No More to start playing. A band like Faith No More was big news in Moscow and worth leaving my apartment for, something I rarely did these days.

I spent most of my time lying on the couch drinking vodka and reading and re-reading the spiral notebooks I’d filled since coming to Russia. I read them over and over, like I was looking for clues. Moscow would fill up a 150-page spiral notebook in a week, if you were lucky. That’s why I’d come here. And things had been going so well. But now, where had it gone? Why had it dried up? Could I make it come back?

“Maybe going somewhere will help,” I thought, as I splashed my face with freezing water and ate some toothpaste.

At the arena, I slouched in between Stu and Betsy. I was drunk, too drunk to be out, and miserable. “What am I going to do, Betsy?” I said.

“You’ve got to find a job,” said Betsy.

That was easy for Betsy to say, because Betsy had mysterious powers. Betsy was so obviously capable that Caterpillar’s Moscow office asked her to manage it despite her knowing nothing about bulldozers, or managing. She spent her days speaking Russian to Siberian site bosses, telling them how to work their new machinery. At night she hung out with friends, or played with her cat, Monster. She even went to aerobics. Betsy was managing to keep not just herself, but also a pet, alive in spite of all this violence and craziness. I, on the other hand, could barely manage to live like a normal person in Gainesville, Florida. This was terrible, I was terrible. I was never going to get to have a pet.

“I can’t,” I said. “I can’t! I can’t write anything and if I can’t write anything I can’t get a job, because I don’t have any skills!” I started to cry.

“Robin,” she said, shaking me by the shoulder, “Get a grip on yourself. Look, you want to write something? Write about this!”

“What do you mean?”

“Write an article about Faith No More playing in Moscow. You could interview some of the fans, ask them about why they’re here. You could even interview the band. You could write about the blossoming of Western music in post-Communist Russia. That would be so interesting!”

I squinted at Betsy. “That would be interesting.”

“I bet you could even get it published in Rolling Stone.”

“You think?” My brain began clicking to life, considering the possibilities. In my fuzzy, disordered state of mind, the gulf between Betsy’s idle suggestion and a monthly “Rock in Russia” column for me at Rolling Stone was easily bridgeable. The more I thought about it the more I warmed to the idea. Holy cow, I realized, feeling vaguely energetic for the first time in weeks, Betsy was right! I’d interview Faith No More that very night and they would be so shocked to see me, a fellow American, asking them questions that they’d have no choice but to take me under their wing. They’d call the editors of all the music magazines back home and say “You won’t believe who we met here in Moscow! And best of all, she needs a job!” This was it, I decided, the transition I was looking for that would help dig me out of the hole I was in. The opportunity had taken its time in coming, but now that it was here, I was ready for it.

My utter conviction that rock and roll would save my life had some basis in reality. Music was what kept me afloat in a town where examples of the life I wanted were scarce. I knew the basic values my mother taught me, like working hard, were good, but they never seemed like ends in and of themselves. We were all supposed to work hard so we could …what? Sit at a cubicle at the call center? Get our ears pierced at the mall? Watch Laverne and Shirley in our dens? Even as a kid I’d realized that I could do all of these things without working very hard at all.

My utter conviction that rock and roll would save my life had some basis in reality.

Most of the people I went to high school with were no help, either. Examining them closely for clues about how to navigate teenagerdom, I realized that my obvious choices were limited to four. I could be a football player or a Christian (these two groups sometimes overlapped), or a Future Farmer of America or a heavy metal fan (these two groups never did). As a pudgy agnostic with no interest in agriculture, by default I found myself hanging out in the Burger King parking lot across from the high school, listening to Motley Crue.

Some of the kids in that parking lot were interesting, though. They had older brothers and sisters who had gone somewhere else once and brought some stuff back. Record albums. My friends and I would sneak into their bedrooms and listen. This was not anything like the music we heard on Rock 105, but it was not the music that got my attention. It was the lyrics. Suddenly here was someone saying out loud "This is not my beautiful house, dammit." Here's somebody saying “Though we keep piling up the building blocks, the structure never seems to get any higher.” I was so unsatisfied, and this music reassured me that it was okay to feel this way. Whatever else I was, at least I wasn’t alone.

The gods of the universe noticed my worship at the altar of the LP and decided to reward my devotion. I’d attend shows that came to my town and Henry Rollins would give me dating advice, or I’d become pen pals with Berlin’s synth player, or end up singing Knoxville Girl to Michael Stipe. Often when I went to see a show I would come to school the next day with some strange story, and my peers began to ask me to go with them to see bands they liked. My powers reached their apex when one of the most popular girls in school approached me at PE one day and told me she’d pay for me to go see .38 Special if I would go with her.

The experiences I had with the people I admired the most – the writers of the lyrics and music that help me hang on – left me with a sense that the closer I got to music, the more interesting and meaningful my life would be. And so it really wasn’t a surprise when I stood up in the stadium bleachers and, swaying slightly, declared, “I’ll do it, Betsy. I’ll go interview Faith No More right now!”

I pushed my way through hundreds of acid-washed-denim-clad Muscovites to the soundboard, which was in the middle of the arena and was surrounded by a six-foot chain-link fence. Not stopping to wonder what might happen, not wavering one bit from the task that lay before me, I hooked my fingers and the tips of my shoes in the fence and climbed over it, dropping to the ground next to the surprised Russian soundman.

“I am a journalist,” I said in an official-sounding voice, pulling my sweater back down over my stomach, “I am here to interview Faith No More.”

“Their bus is out back,” said the man, pointing to a door at the back of the large room.

I was surprised. Wasn’t I supposed to have credentials, or something? Wasn’t I supposed to have my people call their people? But the soundman was not radioing security; instead, he was opening the gate in the fence for me and instructing me to “go through that door and down the hall, and there you’ll find their bus.”

I followed his instructions, and there sat the tour bus, engine idling. What would happen if I tried to get on it? Wouldn’t I need some kind of laminated pass, wouldn’t my name need to be on a clipboard somewhere? No. The Russian driver welcomed me onto the bus and motioned for me to sit down, then launched into a lengthy description of his entire family. This was way too easy, I thought. Clearly, this was meant to be. I had gotten this far – onto the bus! – and now all I’d have to do would be to interview the band as we drove to the hotel. I excused myself to the driver and went to the very back of the bus, where I busied myself trying to think of questions to ask.

After several hours, people began to trickle onto the bus. Russian-looking people and American-looking people, music-looking people and business-looking people; all of them saw me sitting back there and either smiled and nodded or ignored me as they took their seats. I began to relax. I was in. A group of very hairy, tired-looking men boarded the bus. As they walked toward me I could see from the other passengers’ reactions that this must be them. They looked friendly enough. Best of all, they were heading right for me! I clutched the small notebook I always carried with me, ready to go.

“Excuse me,” said one of them, “Who are you?”

“I’m Robin!” I said, “I am an American journalist living in Moscow!”

“Well, you’ll have to get off this bus now.”

“No. What? No. Really? I have to get off the bus? But…why?”

“Because we have to leave,” said the man.

“Oh, man. Really? But, wouldn’t you like to be interviewed by an American journalist living in Moscow?” These people didn’t seem to find my presence in this country or on this bus nearly as novel as I did.

“No,” said the man, gesturing to the bus’s door.

“Okay, but, don’t you need help getting around Moscow? Finding your hotel? Wouldn’t you like a guide?”

“We have a bus,” said the man, “which you need to get off of right now.”

The entire busload of passengers was turned around watching us, their faces hovering moon-like over the backs of their seats. Still sitting down, I looked up at the band as they waited for me to get out of their seats and off their bus. Silent seconds ticked by as I waited for what always happened in movies and what should be happening right now to, in fact, go on and happen. One of them would say, “Just let her ride to the hotel.” Or one of the passengers would recognize me and stand up and say “Wait! I know her! Really, she’s cool,” and then someone would start a slow-clap.

But of course none of this happened. The band stood there, exhausted after their show and annoyed by – face it, there was no one else to blame – me, and the man who had spoken to me pointed again at the door. Shamefaced, not even bothering to work up some kind of huff, I hung my head and walked toward the door. The actual cool people – the people waiting for me to leave so they could ride with the band to the after-party at the hotel – those people snickered and tisked as I passed them.

I stood in the back of the now-empty arena and watched my last chance at a story puff away into the darkness. If I didn’t have a story, what did I have?

Click here to read the next chapter.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

Headspace, a guided meditation app, was a useful tool for my late-stage maturation has been a godsend to me during the pandemic. Click here for a free trial.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.