Red Ticket: My Arrival

“America,” said the man like it was a ribald joke. “Let me ask you, how is the sex with your husband?” “What?” I said, hoping I’d misunderstood him.

Every weekend we serialize Red Ticket, Robin Whetstone’s memoir of her time in Moscow in the early ‘90s. Today, Robin finds out she’s a published writer and is finally accepted by her boyfriend’s family. If you need to catch up, go back and read chapters 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 8-9, 10-11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18.

Chapter 19: My Arrival

by Robin Whetstone

Finally, after a week and a half of daily calls, somebody who knew something answered the phone at the Moscow Guardian.

“Robin?” said Dave, an editor at the magazine. “Yeah, where are you? When’re you coming in here?”

“Am I supposed to come in there?”

“Well, yeah. You’re the writer.”

“Oh,” I said, trying to sound like of course I was the writer. “So, that means you’re going to run my article?”

“It’s running right now.” I heard the sound of pages flipping. “Here it is; page 23. Home cures, right?”

“Right,” I said. It felt like my head was full of warm lint. Six weeks ago I was nothing. But now, my name was in a magazine, and not because I’d gotten arrested or accidentally injured a lot of people, but because I was the writer. I tried to focus as I got the details about the upcoming staff meeting, where I’d get my next assignment. Then I hung up the phone and burst into tears. I had to get out of this apartment before Alexander came of out the bathroom. He was the last person I wanted to share this moment with. I had to find someone to talk to, had to find a copy of this magazine, the one my story was in. I hurried into my room and grabbed my coat, then pulled on my hunting boots and slipped out the door. I spent all morning checking the usual places: Rosie O’Grady’s, the Irish House Bar and Supermarket, Jacko’s Bar, the Hotel Metropole. Nothing.

In my coat pocket was a matchbook someone had given me, from a dollar restaurant called Tren-Mos. Maybe they’d have a copy of the Guardian. I walked up to the metro and took the train to a neighborhood I’d never been in. I knew the restaurant was near this metro stop, but not exactly where. A passerby recognized the street name on the matchbook, telling me to get on sorok pyat, the stop over there. I walked across the street and waited in the falling snow for the bus. After a long time, it arrived. I punched my ticket and sat down in one of the last empty seats as we lumbered into traffic. After a block and a half, the driver pulled over in front of a signless stone building, turned off the engine, and got off the bus. I watched through the window as she walked into the building. Was it time for her 15-minute pererive? Did she have to use the bathroom? Had her shift just ended? There was no way to tell, no way to know when or if she’d come back. Too bad if there was someplace we had to be. We were on our own.

“What do we do?” said a lady with a fur coat and honey-colored hair. “Should we just sit here?”

“Let’s wait,” said an older man, “She’s sure to come back soon.” We sat in silence for another five minutes.

“Well, I’m not waiting anymore,” said a man in a suit, standing up and folding his newspaper. He walked toward the bus’ open door and a handful of people followed him. The rest of us just sat there. I wondered why.

After another five minutes, the driver came back and started the bus. Problem solved, the remaining passengers became strangers to each other once again. We’d been driving for no time when an urgent, rubbery smell filled the bus. The driver pulled the bus over again, and turned it off. Then she stood up and addressed us.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” she said, “The bus is on fire. You must please leave the bus.”

None of the Russians on the bus seemed surprised or upset. Now that the State had collapsed, there was no government money for infrastructure, which meant most things in Moscow were broken. We got to our feet and shuffled off the bus.

Sighing at the heavy sleet that was falling around me, I turned my back on the bus, which was now indisputably on fire, and started walking toward what I hoped was the center of town. The unshoveled sidewalk was icy and hard to navigate. I moved to the curb and stuck out my arm. A man in a Lada immediately pulled over. He said he knew where Tren-Mos was, we negotiated a 500-ruble fare, and I got in the backseat.

“What are you doing in Moscow?” asked the man, who appeared to be in his mid-40s.

“Well, my husband’s Russian,” I said. This was the first answer I gave to every Russian man who asked me a question, regardless of what the question was.

“Akh!” said the Russian man. “Very good. And you are from?”

“America,” I said.

“America,” said the man like it was a ribald joke. “Let me ask you, how is the sex with your husband?”

“What?” I said, hoping I’d misunderstood him.

“The sex! The sex!” cried the man, taking both hands off the wheel and slapping his palms together like a lady patting out a tortilla. He looked over his shoulder at me, raising his eyebrows.

“Watch out,” I said. “Watch where you’re driving.” I decided to pretend I didn’t understand the man’s question. I shrugged and stared out the window as we crawled through the afternoon traffic. Mercifully, he didn’t ask me any more questions. We rode in silence for not very long before there was a thunk outside, and the car pitched and limped.

“Sykha,” swore the man, turning onto a side street. He got out of the car. “Flat tire!” he yelled at me. I got out, too, and stood there watching while the man pulled a jack from the car and squatted down by the tire. “I’ll have this fixed soon.”

“OK,” I said. And then: Wait. Why am I standing here? “Actually,” I said, “I’ll walk.”

“Devushka!” the man yelled at my back. “Come back! I am your ride!”

I was walking down the side street, further away from the main boulevard, deeper into the unfamiliar neighborhood. I was lost, and wet from the sleet. It was 20 degrees outside. I’d been roaming the city by foot and metro for five hours, searching for the Guardian, but had found nothing. Not at Nightflight, the Penta Bar, or Casino Moscow. “This is either a really popular or really unpopular magazine,” I thought. I took a left on another lane, and a different man in a different car pulled up beside me.

“Akh!” said the Russian man. “Very good. And you are from?”

“America,” I said.

“America,” said the man like it was a ribald joke. “Let me ask you, how is the sex with your husband?”

“What?” I said, hoping I’d misunderstood him.

“The sex! The sex!”

“Where are you going?” he said through a crack in his window.

“You won’t know it,” I said, still walking. “Tren-Mos restaurant.”

“I know just where that is,” he said, braking the car. “It’s right over there.”

“Four hundred?” I said.

“Nyet, nyet, I can’t take your money. It’s snowing, and it’s right over there.”

I got in and we rode down the side street and turned right onto a bigger avenue. A few blocks ahead of us, I could see the Tren-Mos sign.

“You are American?” said the man as we waited for the light to change.

“No,” I said. “I’m from Canada.”

***

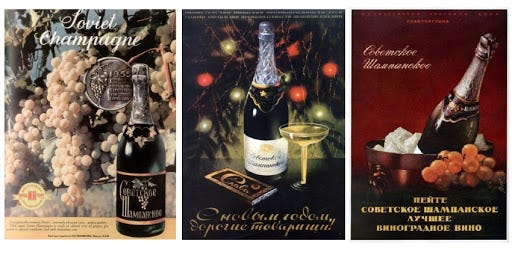

Many, many hours later, the taxi I’d fallen into pulled up outside of my apartment building. I let myself in silently and was taking off my boots in the hall when Lyosha appeared from around the corner. He was holding a bottle of Soviet champagne in one hand and wearing a sharp black suit. “Congratulations,” he said. “Now you are writer.”

He held me by my perfectly healed wrist and pulled me into the kitchen. His mother, sister, and even Alexander were standing beside a table that was laid with fancy pastry.

“Oor-aaaahhhhhh!” they all shouted at me, waving their arms over their heads.

“Robinkaya!” cried Valentina, who seemed to be near tears, “We are proud of you!” She threw herself on me like I was on fire and she was trying to put me out. It was one in the morning. People had been handing me drinks and yelling oorah for the last six hours.

“This is the happiest you have ever been,” I realized. I was grateful to be able to recognize it while it was happening, instead of in retrospect. Lyosha handed me a champagne glass.

“Spaceebo bolshoi,” I said. “Thank you so much.”

To read the next chapter, click here.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Want a way to send gifts and support local restaurants? Goldbelly’s got you hooked up.

I used this to order scotch delivered right to my door. Recommend.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.