Red Ticket: Rude Awakenings

“Get up,” she said in a flat voice that scared me. “Get up right now and cook this chicken.”

Every weekend we serialize Red Ticket, Robin Whetstone’s memoir of her time in Moscow in the early ‘90s. Today, Robin moves in with Lyosha’s family because he’s in jail. It does not go swimmingly. If you need to catch up, go back and read chapters 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 8-9, 10-11, 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16.

Chapter 17:

by Robin Whetstone

Not long ago, Lyosha would have gotten a year of hard labor for breaking a window to get in his own apartment. (“The way it should be,” the dejournayas would have said.) Instead, he bribed his way out of jail with 500 American dollars and a carton of Marlboro Reds. He went straight from jail to his best friend Alex’s apartment, where he stayed. I moved in with Lyosha’s parents and sister. Just imagine how excited his mom and dad were to see me, the American with the fried hair and the fake job and no place to live because her boyfriend, who was also their son, was in jail.

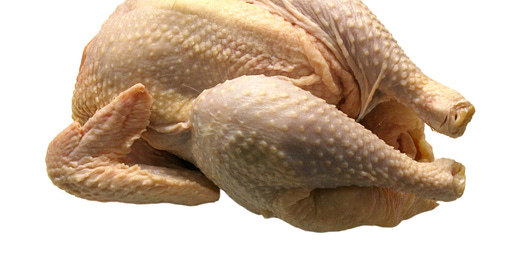

Lyosha’s dad, Alexander, had knocked on the door 15 minutes after the landlady left. He did not speak to me as he loaded our few possessions into his Lada, then pointed for me to get in the back. When I’d settled myself among Lyosha’s dress shirts and my suitcase, Alexander handed me two more things: a big mesh bag of dates, and a whole, unwrapped chicken that had been in the refrigerator. I put the dates on the floor by my feet and held the naked chicken on my lap, like an infant.

We rode in silence through the city, the buildings and people a late February gray. Wet, sloppy snow pelted down. I wasn’t expecting Alexander to speak to me, so I wasn’t paying attention when he did.

“Could you repeat that, please?” I asked him in Russian.

“I said,” he said loudly and slowly, looking back at me and scowling, “I hope you two are using birth control, because we don’t want any American grandchildren.”

***

They put me in Lyosha’s room and did not say anything at all to me for several days. I barely left the room during this period and had run out of spiral notebooks. The only book I had with me was Cold Sassy Tree, which I’d found in a bar and read twice already. I had time to reflect.

I’d been in Moscow for 35 days, and already I had been attacked by ruthless gangsters, gotten a job as a writer, shacked up with my Russian boyfriend who was also possibly a mobster, and moved three times. I thought about these events and felt very unhappy. Things had been going so well, but now I was stuck in this domestic Soviet backwater. And what about Lyosha? Did this mean we were broken up? I wasn’t mad at him for leaving me here. Maybe the lady who wouldn’t let us rent the apartment had been right. Maybe Americans were trouble. Maybe he didn’t want to see me after what had probably happened to him in jail. I was going to have to find my own way out of here, and that meant getting a job. I’d submitted my article about Russian superstitions to the Moscow Guardian, but they hadn’t called. Then again, I was sort of hard to get in touch with.

“You’ve only been in Moscow for five weeks,” I told myself. “You’ve barely gotten started. Don’t worry.” There were nowhere near enough journalists in Moscow to cover the wars that were breaking out all over the former Soviet Union. If the Guardian fell through, I could go to Chechnya, or South Ossetia, and write about that. I didn’t care where I went. Any place was better than here.

Lyosha’s parents were crazy, sinister people. Just that morning, at 5 a.m., the door to Lyosha’s room had flown open and Lyosha’s father had burst in, already shouting. The family had decided what to do with me and had sent Alexander to do it.

“Devushka!” he shouted, “How many kilograms in a bushel?”

“Shto?” I said blearily, sitting up. Was this a test? What would happen if I passed? “What?”

“What’s the matter? Don’t they teach you math in America?” He sneered and stepped back into the hall, slamming the door.

Now it was the evening of my third day here, and I had only left the room to use the bathroom and fill up my camping pot. But tomorrow morning would be different, I decided. Tomorrow morning I’d sneak out of Lyosha’s room and use the phone. I knew they had one in the kitchen; I’d seen it the day that Lyosha’s mother had looked at my burn. I’d wait until Lyosha’s mother (whose name I still didn’t know) left for work and Alexander went in the bathroom. Then, I’d call the Guardian, and also, my mother.

It felt good to have a plan. I lay down on Lyosha’s cot, which was a thin pad on top of a plywood board, and waited to fall asleep.

***

I was sleeping soundly when the door once again banged open. In the doorway, backlit by the hall light, was Lyosha’s mother. In one hand she held the chicken I’d brought with me from 66 Sukharevskaya. She held it by its neck stub, its legs dangling. In her other hand was a very long knife.

“Get up,” she said in a flat voice that scared me. “Get up right now and cook this chicken.”

I scrambled out of bed and followed her into the kitchen. The clock on the stove said it was midnight. Lyosha’s mom set the chicken down on the counter and herself down at the small dinette table. She picked up a newspaper and began flipping through it. I turned to the chicken. The only parts of a chicken I’d had experience with were the tenders parts and the nuggets area. I had never seen a chicken with so much stuff still stuck on it. If I could somehow split it in two, I decided, I could sauté or something the two breast halves. Behind me, the newspaper rattled. Lyosha’s mom was sitting there, waiting. I had to do something. The knife Lyosha’s mom had held lay next to the chicken. I picked it up and poked the chicken in the chest. The blade sunk half an inch and then hit bone.

“Get up,” she said in a flat voice that scared me. “Get up right now and cook this chicken.”

“I’m sorry,” I thought as I poked it again just a little harder and in a different place. I stabbed the chicken again, harder this time. I tried to tell myself as I continued stabbing that this was a necessary part of the preparation. Tenderizing. But as my frustration and anxiety grew so did the arc of my arm until finally I was not just stabbing the carcass in front of me, but murdering it all over again. I saw myself holding the knife handle in my fist, wild-haired and sweaty, thinking nothing, blindly plunging the blade into the naked chicken as it shielded itself behind the shower curtain. No, wait. Get a hold of yourself.

The knife wasn’t working; the chicken was still intact. “I’ll just rip it apart with my hands!” I decided. I grabbed the chicken by the clavicle and pulled as hard as I could. The tiny bones at the top of the breast splintered, but the bird stayed in one piece. I threw the chicken back down on the counter and then grabbed it up again like a football, sinking my fingers into its flesh, pulling and twisting and pushing. I was getting scared, desperate. This was taking too long, and involved audible grunting noises. I knew that soon Lyosha’s mom would look up from her newspaper and see me wrestling with this chicken. When this happened, she would punish me. She’d hang the bird around my neck and make me sit outside where the neighbors could see me, a chicken stockade. I had to get this done, right now.

I looked around the kitchen for something I could use as a cudgel. A rolling pin? A cast-iron skillet? Ah, there it is: a Pepsi bottle! I grabbed the glass bottle and whammed the chicken with it as hard as I could. Dimly I was aware that I had lost all reason and had given up trying to prepare this chicken and was now just assaulting it, but I couldn’t stop. The thick bottom of the Pepsi bottle thudded against the bird’s flesh and I was panting as I raised the bottle and brought it down again, up and down, over and over.

There was a sharp rustle of newspaper as Lyosha’s mother leaped up from the table and ran up behind me. “What are you doing? What are you doing?”

“Bones!” I yelled, bringing the bottle down, “This chicken has bones!”

“Yes!” said Lyosha’s mother, who was visibly frightened, “Chickens have bones!”

“Not in America,” I said. “American chickens don’t have bones.”

Finally, hours after I started, I had scraped together a stringy pile of meat big enough to feed a very small child. I sautéed the scraps with sour cream and paprika, hoping the sauce would cover the evidence of my crime. Lyosha’s mother surveyed my creation and nodded.

“Ladno,” she said, “You may go to bed now.”

I tottered off to my room and lay on top of the bed, afraid of what would happen if I let myself sleep.

To read Chapter 18, click here.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Want a way to send gifts and support local restaurants? Goldbelly’s got you hooked up.

I used this to order scotch delivered right to my door. Recommend.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.