Red Ticket: 66 Sykharevskaya

"On a telephone table in the foyer, there was a gun."

Every weekend we serialize Red Ticket, Robin Whetstone’s memoir of her time in Moscow in the early ‘90s. Today, she moves into her new apartment and manages to avoid getting deported in the process. If you need to catch up, go back and read chapters 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 8-9, 10-11 and 12.

Chapter 13. 66 Sykharevskaya

by Robin Whetstone

The deal was this: Lyosha would show me Moscow and keep me from getting killed, and I would be his American girlfriend. We’d split the rent. The only thing standing in between me and this plan was Sasha. Sasha worked for the language school I’d enrolled in, and which had provided me with a dorm room and a visa to enter the country, which the school kept at its office. I had asked the language school to give it back to me, but they’d refused.

“You have entered country to be student,” the director told me when I called. “If you are not student, there is no legal reason for you to be in Moscow.”

We argued back and forth for a while, me explaining that the dorms were not safe, and that I had a reputable job, him protesting the illegality of it all, until finally I wore the man down. He agreed to send his assistant Sasha around to drive me to my new apartment to check things out. If Sasha saw that everything was legit, he’d give me my visa and I would be free. Otherwise, the school would revoke my visa and I’d be deported.

I was not happy with this compromise, because I myself had not yet been to the apartment. I had only an address, and the key Lyosha had given me the day before. I had no idea what or who would be there when Sasha and I arrived. I stood outside the dorm building with my suitcase, looking up and down the empty boulevard for a car that might be Sasha’s and stomping my boots to keep warm. I felt sick, but not from nervousness. I felt sick because I had just drunk six shots of vodka, something I was not used to doing at 10 a.m. on a Thursday.

The drinking had happened when I crashed a meeting with Moscow State University’s Folklore Department to ask them about Russian superstitions for an article I was working on. Apparently no one wanted to talk to the folklorists about anything, ever, so a surprise visit by an American was big news. They’d snagged me like one of those bird-eating spiders on the Discovery Channel and broken out the pastries and vodka. Soon I was very drunk, so it was easy to talk about how the Russian state, starting with Prince Vladimir in 988, used religion to consolidate power. The Soviets killed the church for a while, we all agreed, but they applied its religious rituals and esthetic to Stalin’s regime. He was the new Jesus, the benevolent father leader. The imminent arrival of the true Communist state was the replacement heaven on Earth, the principle that ordered everything. It was what gave big things and small things their meaning. What will happen now that it’s gone, we all wondered. What were they all supposed to believe in?

After a few minutes of standing in the cold, trying to sober up, I saw a Lada round the corner. I climbed into Sasha’s car and said how do you do, hoping to give off an air of mature professionalism. If I came off as someone who spent her mornings drinking vodka with folklorists, it could jeopardize my future in Moscow. Sasha was in his 40s and spoke excellent English. The first thing he asked me when I got in the car, even before asking where we were going, was whether I had any American music we could listen to on our drive.

“I certainly do!” I said, opening the suitcase that lay on the backseat next to me. I had brought my entire cassette collection with me from America, and was as excited as he was to finally be able to listen to them. We drove through town toward the address Lyosha had given me as Tom Waits and The Replacements and Al Green sang about diners and boners and loneliness. At a stoplight, Sasha turned to me and got down to business. “So,” he said, “Who are you moving in with?”

The news that I had a new apartment had come the night before. I’d found out this morning, right before the folklorist interview, that I might get deported. There was too much going on; I hadn’t thought at all about what I was going to say to Sasha. And now it was hard to think very clearly about anything.

“Akh,” I said, “I’m moving in with a very old lady named Natasha.”

“Horrosho,” said Sasha, “I will look forward to meeting her.”

“Oh no,” I thought. “The chances that Natasha will be there are slim. But what if Lyosha is there? How will you explain this?”

“Well,” I said, “She works as a telephone operator, so she probably won’t be there. But her son might be there. He’s there all the time. It’s sort of like his second home, you see.”

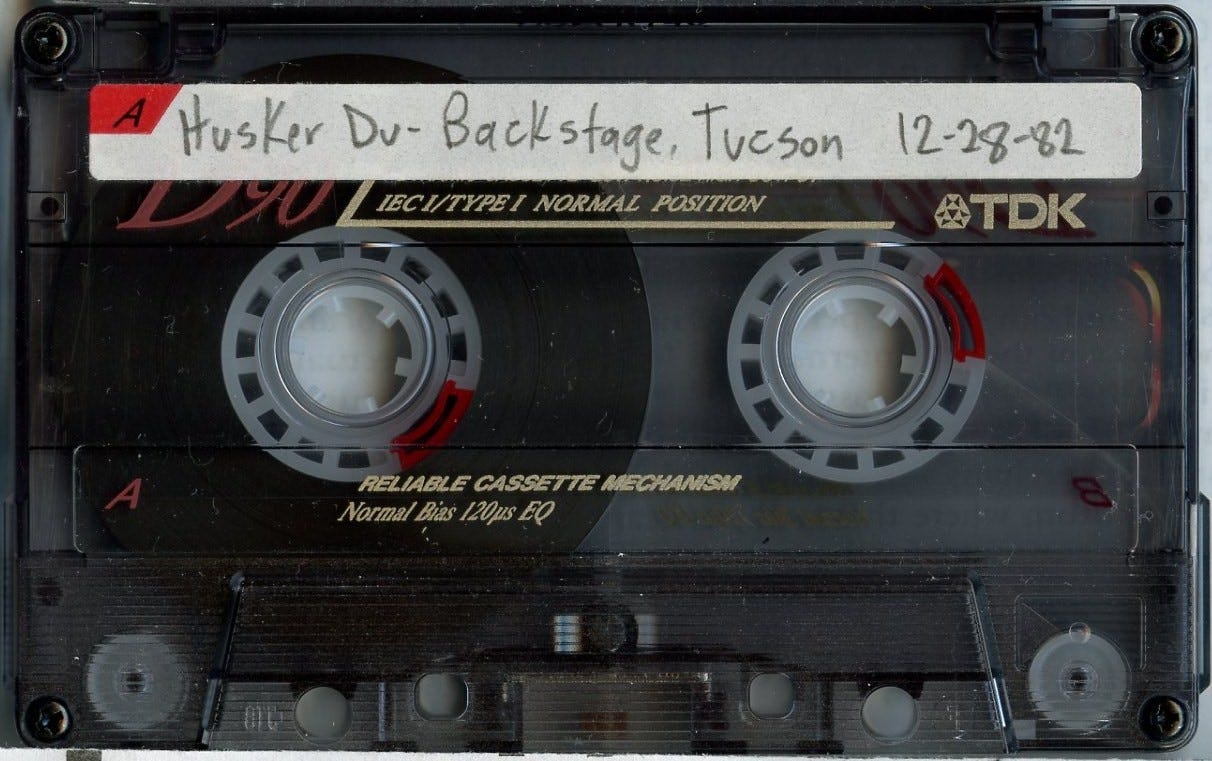

“I do see,” said Sasha, and I could see that he really did. But for now, at least, it seemed like he wasn’t going to say anything. One further question would have exposed my obvious lies, but instead, Sasha drummed his fingers on the steering wheel and bobbed his head to Husker Du. “This is great music,” he said. “I love music!”

We pulled up in front of a cream-yellow, 12-story building that had probably been built in the ‘50s, and took the elevator up to the 6th floor. I was in an agony of nervousness as I turned the key in the lock. What would my new home look like? What might Sasha see?

I opened the door and we walked into an unlived-in 2-room apartment. It was furnished with a couch in the living room that folded down into a bed, a wall unit of shelves, and a table and chairs pushed into the corner of the bright and cheerful kitchen. There was even a TV. What there wasn’t was any sign at all of habitation. No pictures hanging on the walls, or dishes in the sink, or towels in the bathroom. No clothes in the closet or knickknacks on the shelves. This Natasha, she sure was a minimalist.

There was only one thing besides furniture in the apartment, and both of us saw it as soon as we opened the door. On a telephone table in the foyer, there was a gun. A big black 9mm gun, brooding there on the blonde wood like a malevolent beetle. Underneath it was a slip of paper bearing Lyosha’s masculine handwriting. “Take this gun,” is what it said.

I turned to Sasha, who was staring at the gun and the note underneath it. “Ha ha,” I said, “Looks like no one is home.”

“Robin,” he started, and I reached out and grabbed his wrist and stared into his eyes.

“Thank you so much for driving me here, Sasha,” I said. “I am very relieved to get out of the dorms. They were not safe for me. And now that I have a job working at a magazine and a decent place to live, I’m sure I will be fine. I want to give you this as a token of my thanks.” I held out the mix tape we’d been listening to in the car.

“Really?” Sasha tried to hide his excitement, and failed.

“Yes, absolutely. Please take it.” I put my hand over my heart. “From your American friend.”

“Thank you,” he said, “Thank you so much!” Sasha took my folded-up visa out of his shirt pocket and handed it to me, replacing it with the tape I’d just given him. We shook hands, he wished me good luck, and then I was alone in the apartment with my suitcase and my gun. I went into the living room and lay down on the couch, and fell immediately into a deep and dreamless sleep.

Read the next chapter here.

Don’t miss any chapters in Red Ticket by subscribing here.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Want a way to send gifts and support local restaurants? Goldbelly’s got you hooked up.

I used this to order scotch delivered right to my door. Recommend.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.