Red Ticket: Once in a Lifetime

“I am so sorry,” she said, “We would never annihilate you.”

This weekend in Red Ticket, Robin gets invited to a dinner party, which is not as fun as it sounds. Being an American in a Russian’s home means you’re in for a long night. This starts out like all the others with questions, zakuski, and lots and lots of vodka. Then it takes a turn.

If you need to catch up, go back and read chapters 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 8-9, 10-11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28.

Chapter 29: Once in a Lifetime

by Robin Whetstone

I was arranging the flowers I’d purchased at the metro stop in a glass on the kitchen windowsill when there was a loud banging on the door, as if someone were kicking at it. I padded down the hall in my house slippers and opened it a crack. In the lobby stood my landlady, Nina, who lived with her extended family in the building next door. She was struggling to hold a large brown bag of something. Was it dog food? Potting soil? I opened the door and she peeked around the unwieldy bag.

“Good afternoon,” huffed tiny Nina. “I have brought salt.”

“Oh,” I said. Had I asked for salt? I took the bag, which weighed 25 pounds, and set it behind me in the hall. I knew that the traditional Russian welcoming gifts were bread and salt. Maybe Nina was out of bread and had decided to double-down on the sodium. “Spaceebo bolshoi, Nina. I can always use salt.”

“Yes,” she agreed. Then she stood there without saying anything else.

“Would you like to come in?” I asked her.

“Oh no no,” she said, waving her hands. “It is just that, I would like to invite you to our home tonight for dinner.”

“Oh no,” I thought, “dinner.” Russians were forever inviting you to dinners that, though wonderfully hospitable, tended to go on for hours and hours and involved highly formalized rituals of gift-giving and toast-making. You, the guest, were the honored visitor and could not escape scrutiny. You either answered every question that was asked of you, ate everything that was set in front of you, and accepted every lavish gift your hosts could not afford to give you, or else you dishonored your hosts and risked a blood feud that would last generations and inspire epic poems. It was exhausting.

“Oh, Nina, that’s very kind of you. But I have so much work to do, and I’m still unpacking, and –“

“Nonsense,” said Nina. “You are odnokaya devushka, so you will come and eat with us.” That phrase, “odnokaya devushka,” meant both “lonely girl” and “girl who is alone.” I was unsure in which sense she meant it, and this bothered me. Everyone on this small street knew I lived here by myself – it was big news when the American girl moved in. But did they think I was lonely?

I sighed. “Okay, Nina. Thank you.” Avoiding a six-hour dinner with Nina and her family wasn’t worth insulting her, so a few hours later I grabbed the flowers out of their glass and walked to the building next door.

Like my apartment, Nina’s was on the first floor. And also like mine, it had a huge, screenless window in the living room that took up most of one wall. In my apartment, the window swung open to let in the air and the smell of the lilacs outside. But in Nina’s apartment, the windows were all covered up; blocked off by multiple tall shelves that crowded the walls. There was stuff – furniture, piles of clothes, books, knick-knacks — covering every inch of the room, which was made even more claustrophobic by the number of people in it. Sitting on various divans and chairs were the seven people who lived here: Nina, her husband, their 17-year-old son Marat, Nina’s brother Vitya and his wife, and Nina’s sister and her husband. It was clear by the scowl Marat gave me when he opened the door that Nina and her family had moved in with Nina’s siblings in order to rent their two-bedroom apartment to me, the lonely girl. I stood in the entryway to the living room while the family stared at me. I felt exposed, like I wanted to run away.

“Sit down, sit down!” said Nina, leaping to her feet and gesturing at an empty place in the middle of the couch. “We have zakuski! You must eat!” I did as I was told, awkwardly balancing a plate of cucumbers and kielbasa and potato salad on my knees. The family made no move to join me in eating; they just sat there and watched me as I chewed. It was hot in here, stuffed on the couch next to Uncle Vitya, and the sausage I was chewing tasted oily and tough.

“Your husband. Will he be joining you from America?”

“I don’t have a husband,” I said. “I’m not married.”

This was the wrong answer.

“Tak,” said Nina at last. “When will your husband be joining you?”

“What?” I had said nothing to Nina about a husband when she’d rented the place to me.

“Your husband. Will he be joining you from America?”

“I don’t have a husband,” I said. “I’m not married.”

This was the wrong answer. Nina and her family looked at each other with expressions that said they were sure I was lying. “You mean to say,” said Vitya, “You came to Russia alone?”

“She has family here,” said Nina, frowning at Vitya. “Your family is from Russia?”

“No,” I said. “We’re originally from Scotland.”

“Well then,” said Vitya, “why are you here?”

“Because I think Russia is interesting,” I said.

Vitya’s eyes widened and the rest of the family looked uncomfortable, like I might be dangerous. “So, you mean to say you meant to come here?”

“Da,” I said.

“Why?” said Nina. She didn’t have to say what she was really thinking. I could see it right there on her face. You had the luxury of choosing anything, and you chose this?

I sat in the silence, trying to come up with an answer that wasn’t insulting. I came here to have a holiday in your misery? So I’d have something to write about? I couldn’t think of anything to say. Finally, Vitya stood up. “Never mind,” he said, picking up an unopened bottle of vodka and unscrewing the top. “Let’s have a toast to our American guest.” He poured the bottle into eight shot glasses and raised one of them high above his head. “To our American guest!” To lovely women!”

“To our American guest,” said Nina, “Let’s drink to health for those who have it!”

“To our American guest,” said Nina’s sister, and then also Nina’s husband, and her sister-in-law, and also her brother-in-law. When it was Marat’s turn to toast, he simply held up his glass. “To health,” he said, not specifying whose he meant. He drank his shot and left the room.

Then it was my turn. Toasting, which was almost never done in America unless someone was getting married or out of prison, was very important in Russia. I was the last toaster, the guest of honor, and the pressure was really on. I stood up, very drunk after seven consecutive shots of vodka, and shouted, “Bu zdorove!” which is what you say after someone sneezes.

“Sit down, sit down,” said Vitya. He patted a thick book on the coffee table. “Let us show you our family photos.”

“Oh no,” I thought, as Vitya opened the binder and another bottle of vodka. “Strangers getting married.” The room was airless and cramped and I was feeling too hot again.

“This,” said Vitya, pointing to a sepia-toned picture of a pre-teen boy in a uniform, “Is Max, our cousin. You see he is wearing a uniform? This is because he fought in the Great Patriotic War. He was in the advance guard of youths that protected the towns outside of Moscow from the Nazis. His job was to put on a grenade and throw himself on the tanks.”

I was certain I’d misunderstood him. “You mean, to throw grenades at the tanks.”

“No,” said Vitya. “He strapped a grenade to his chest and blew up a German tank. We are very proud of him.”

“His job was to put on a grenade and throw himself on the tanks.”

I was certain I’d misunderstood him. “You mean, to throw grenades at the tanks.”

“No,” said Vitya. “He strapped a grenade to his chest and blew up a German tank. We are very proud of him.”

Clearly I had underestimated this photo album. I leaned forward as Vitya continued. “This is Nina on the civil defense brigade.” He pointed at a much younger Nina, wearing a red scarf and laughing with her friends as they hefted metal buckets of what looked like sand.

“Was this during the war?” I was confused. Nina was my mother’s age. What was she doing in WWII?

“No, this was after. In the late ‘50s, during the Cold War. On our subotniks” — mandatory volunteer Saturdays when neighbors came together for civic projects — “we practiced drills for nuclear war.”

“Really?” I was excited by this news, because I finally had a story of my own to share. “My mother told me about those drills. They used to have to hide under their school desks to protect themselves.” My hosts looked at me in confusion so I jumped up and demonstrated, crouching under the leaf of the coffee table and covering my head like the kids I’d seen in those grainy films. “They used to have to go to the train station and practice evacuating. She told me about that. She said she was terrified.”

“I am so sorry,” she said, “We would never annihilate you.”

“Me neither,” I said.

The family was silent, looking around uncomfortably. “You terrified my mother, Nina,” I might as well have said. I cleared my throat, embarrassed, and sat back down. Vitya poured us all another vodka.

“You are interested in history?” said Vitya. “Ladno, maybe you will like these.” Vitya flipped to a section of the book showing pictures of a younger version of himself, dressed in uniform and standing on a beach next to palm trees. “I am in Cuba, here.”

“What year was this?” I asked him, though I already knew.

“1962.” The family was quiet, watching me.

“Boje moy,” I tugged at Vitya’s sleeve. “This was during the Cuban Missile Crisis, right?”

“Yes,” said Vitya, “But how do you know about this? You are young.”

“We live in Florida,” I said. “Cuba’s only 90 miles away. People still talk about it. Mom was absolutely certain they were all about to be annihilated.”

“So was I,” said Vitya.

We all looked at each other for a couple of silent moments. Finally, Nina spoke up. “I am so sorry,” she said, “We would never annihilate you.”

“Me neither,” I said.

***

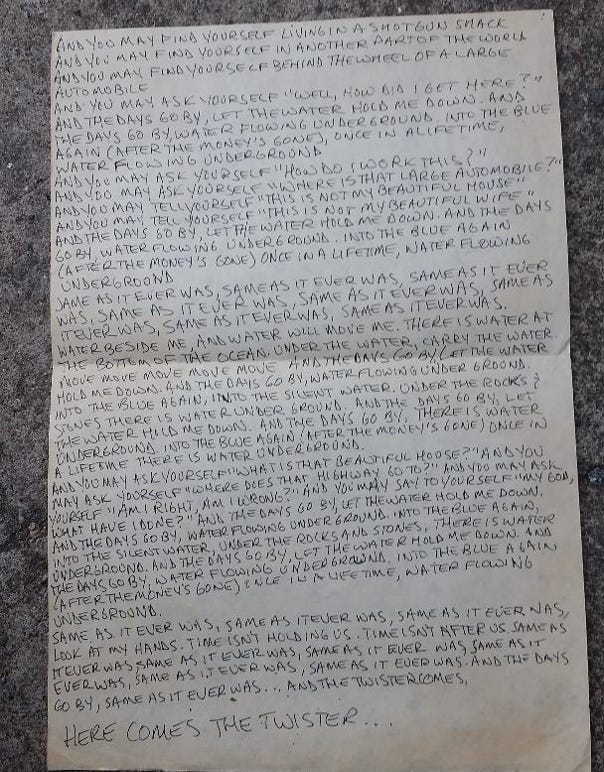

Later that night, after the plates were cleared and the vodka was drunk and the dinner was over, I sat in my apartment, looking at the 1950s-era curtains that hung in my living room window, and which always made me think about Dave Brubeck. I looked around in the quiet at the blonde wooden end tables, the red Bakelite telephone, and the velvety orange wallpaper. Somehow I had landed in some alternate universe where people as friendly and solicitous as my own mother spent their youths hauling buckets of sand and guarding missile bases while she spent hers hiding under desks and getting elected homecoming queen. I felt sick from the vodka, but mainly I felt acutely confused by everything, not sure what to think. I needed something to help me get grounded again. I went over to my spiral notebook on the table and took my time writing out the words I needed to remember. I worked slowly, because I was drunk, and this was important. When I finished, I got up and went into the small bathroom. I taped what I’d written on the wall directly in front of the toilet, which is where I put the things I needed to remember.

To read the next chapter, click here.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Want a way to send gifts and support local restaurants? Goldbelly’s got you hooked up.

I used this to order scotch delivered right to my door. Recommend.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

Headspace, a guided meditation app, was a useful tool for my late-stage maturation has been a godsend to me during the pandemic. Click here for a free trial.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.