Red Ticket: The Eponymous Chapter

“You want to know what is main difference between you and me? I will tell you story."

Every weekend we serialize Red Ticket, Robin Whetstone’s memoir of her time in Moscow in the early ‘90s. Today, Lyosha explains what a Soviet passport means in post-Soviet Moscow. If you need to catch up, go back and read chapters 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6, 7, 8-9, 10-11, 12, 13, and 14.

Chapter 15: Red Ticket

by Robin Whetstone

“Wake up, please.” Lyosha stood over me, poking at my shoulder. “Robin, please. Wake up.”

I sat up on the couch bed and shielded my face from the overhead light. “What time is it?”

“Two-thirty in morning.” Lyosha shrugged out of his suit jacket and sat down on the edge of the bed. He leaned forward, untying his shoes. “We have four hours.”

“OK,” I said. “I’ll get ready.”

***

Lyosha and I were bound to each other by decades of mistrust, by the intensity of feeling being afraid of someone can bring. I grew up in Jacksonville, a military town. Communist Cuba was right over there. We all remembered the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Khrushchev and Kennedy came this close to nuclear war. Our house sat across the main highway from an important naval base; 50 miles north was a nest of nuclear submarines.

“Oh yeah, we’re toast,” the residents would brag. “One of the first to go.”

Everybody saw The Day After, and Threads. Everybody read On the Beach and cheered the democracy-saving hotties in Red Dawn.

Alas Babylon, a story about Florida getting mostly obliterated in a nuclear war, was required reading in the tenth grade. Rita, the Hispanic sexpot, was the character who troubled me the most. She was not only trashy, but greedy. She spent the apocalypse robbing dead people of their jewelry, and this led to a skin-melting, fingernail-peeling, multi-paragraph death by radiation poisoning. Metal of any kind attracts radiation, the handsome protagonist explained while standing over Rita’s carcass. Sucks it right up and holds it there, up against your skin.

I was 15 when they made us read this. Nuclear war seemed pretty imminent, and I knew if there was one I would never get my braces off. All the orthodontists would be dead; there’d be bigger things to worry about. The same thing would happen to me that happened to Rita. Weeks after the bomb dropped, my mouth would be a shredded, dripping hole. There’d be nothing anyone could do.

But then a miracle occurred. My braces came off, Communism collapsed, and now, seven years later, I was sitting with this man in a Moscow kitchen, a bottle of whiskey and a bag of walnuts on the table between us. Lyosha finished the soup I’d made earlier in the day, pushed the bowl aside, and lit a Dunhill. I took out my notebook as he started to sing.

***

“Broad and yellow is the evening light,” Lyosha smoked and sang while I transcribed his words. I’d asked him to tell me about the songs he’d learned as a child, and he told me he’d sing me his if I’d sing him mine. He continued:

“The coolness of April is dear.

You, of course, are several years late,

Even so, I'm happy you're here.

Sit close at hand and look at me,

With those eyes, so cheerful and mild:

This blue notebook is full, you see,

Full of poems I wrote as a child.

Forgive me, forgive me, for having grieved

For ignoring the sunlight, too.

And especially for having believed

That so many others were you.”

“Hang on,” I said, as I wrote down the last few words. I put my pen down and looked across the table at him.

“Anna Akhmatova,” he said, stubbing out his cigarette. “Now you.”

***

The year Lyosha finished high school, 1991, the world fell apart. His classmates graduated into a society no one had prepared them for, and most were left rudderless and drifting. But not Lyosha. The minute Communism collapsed, Lyosha got to work.

“Learning computers,” was the vague answer Lyosha gave strangers when they asked what he did. This answer was true, but it left out some important details. Why would a British telecom company hire a 19-year-old boy who had never even seen a computer to work on their computers? Why would they pay him ninety American dollars a week and spend time teaching him basic computer skills? What were they getting out of it?

Lyosha didn’t know computers, but he did know Moscow. He got his start at 15, selling trinkets to tourists on the Arbat, and moved up the black-market ladder as his experience grew. By the time he got hired by his company as a “computer engineer,” Lyosha had the contacts the company needed to survive in Russia. He knew whom to call, how to bribe, and when to ask a favor. Without this knowledge, nothing got done.

Lyosha worked at this company every day from eight to five. Then at 6 p.m., he went to his real job, the one that kept him in fancy suits. Lyosha bartended every night at the Olympic Penta, a dollar hotel for foreigners. He poured drinks and cracked jokes and made friends with the bankers and oil executives and criminals who packed the bar each night. The Olympic Penta bar was where Lyosha learned about the new world he lived in. It was his college, and he was determined to make it pay off. Lyosha was going somewhere, it was very clear. Lyosha was going to get out.

***

It was another 3 a.m. kitchen conversation, but this time it wasn’t going well. I was sitting at the table taking notes while Lyosha paced in front of the sink, telling me the story of his friend Serge.

Serge was 19 when the State threw him in the jolty dom, Russian slang for the madhouse. His black-market postcard empire had become too lucrative, too threatening. He was disappeared into an insane asylum for years and released only after the USSR collapsed. The first thing he did when he got out was buy himself an apartment. He was one of the first private landowners in the country and was famous among his friends for his wit and resilience, but it came at a cost.

“Look at you, sitting there, thinking about article you will write.” Lyosha stopped pacing and looked at me with disgust. “You think this is interesting, but to me, to us…

“You want to know what is main difference between you and me? I will tell you story. Back before Revolution, during Tsar, Russians went hunting for wolves. Teams of men going into forest, walking for days to find the places where wolves live. They mark it with red flag, so everyone will know. So they will find it later.

“They call this flag ‘red ticket,’ the signal to hunters that wolves can be shot here. They return and hide themselves behind snow bank, at edge of trees. The men call like wounded animals, and wolves run out of forest toward them. The wolves are fooled, running straight into guns of hunters. They have no chance to escape.”

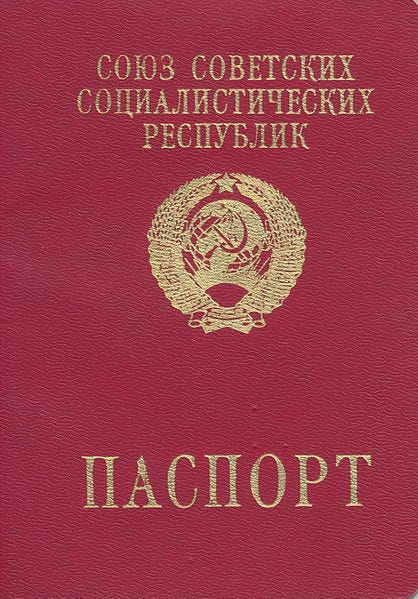

Lyosha yanked open a drawer in the kitchen counter. He pulled out his Soviet passport with its dark maroon cover, and shook it at me. “Today, Russians call this ‘red ticket’.” He threw the passport on the table in front of me. “Just like with wolves.”

Lyosha turned on his heel and left the kitchen, closing himself up in the bathroom. I looked at the table, sticky with the rings left by our glasses. The passport lay there among the ashtrays and walnut shells. I heard the shower go on, a signal that our conversation was over for the night. I got up from the kitchen table and put Lyosha’s red ticket back in the drawer, then sat down and opened my spiral notebook.

To read the next chapter, click here.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Want a way to send gifts and support local restaurants? Goldbelly’s got you hooked up.

I used this to order scotch delivered right to my door. Recommend.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.