Red Ticket, chapters 2-3

Robin Whetstone is back with more from her Moscow memoir

In the first chapter of her Moscow memoir, Robin Whetstone, a Georgia-based writer I’ve known since we worked in Moscow together, explained why she came to Russia. Today, Robin is gifted an egg and a pot.

Hussein

In America in 1993, we’d won the Cold War and had a president who played the saxophone on TV. We were on the cusp of the dot-com bubble, and on the kind of world where everyone knows what a “dot-com bubble” is. Everybody was drunk on victory, heading off into a golden future of Nirvana albums and internet pet stores. Journalists wrote articles about the end of history. September 11 was just a normal day. Columbine was still six years away.

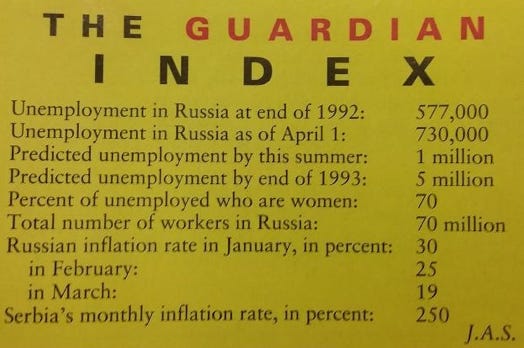

But in Russia, the ostensible loser of the Cold War, 1993 was the most brutal of the post-collapse years. The country was two years into Yeltsin’s disastrous “shock therapy” approach to insta-Capitalism. The State, which had meddled in the most minute details of people’s lives for the past 75 years, threw up its hands and said, “Y’all are on your own now; sorry about that.”

The subsidies that had propped up food production, housing, healthcare, and education ended immediately. State control over how much things cost, which had kept prices artificially low, ceased all at once. Industries and infrastructure that had been owned by the government were instantly privatized, sold to anyone who had the money to pay. Where once the city’s water treatment plant belonged to the Soviet government, now it was owned by some guy named Boris.

Who were these people, Russians asked each other in 1993, as a handful of men bought up nearly all of Russia’s assets. They used money and connections to become billionaires overnight, and the papers were full of their names: Berezovsky, Potanin, Malkin. The city was seized with violence as oligarchs and lesser gangsters consolidated their power and fought over their turf.

I was a 22-year-old with a brand-new Russian degree, so I thought I knew a lot about the country. But I didn’t know any of this. I just knew I was hungry. I looked at the Khrushchev-era desk in my dorm room, upon which I’d arranged the items from my carry-on bag. Three spiral notebooks, three ballpoint pens, my big red Katzner’s dictionary. Five hundred Trojan-brand condoms in a mesh bag. A photograph of my mother and grandparents, vivid under the live oaks. Three small cans of tuna. That was it.

I cursed the fate of the one big suitcase I’d checked on my flight, which my driver said had “disappeared.” Inside it, I had packed mostly food: ramen, peanut butter, granola bars, raisins. I’d even packed a small camping pot. I’d been to Russia before, in 1991, and knew better than to come here without a pot.

“Disappeared where?” I wondered now, staring at a tuna can. There was really no telling.

There was a knock on the outside door to the hallway. I opened my room door and stepped out into a small shared foyer. The room next to mine was empty, locked. The small rooms housing the shower and toilet sat in deep shadow, their doors half-open. I padded across the foyer and opened the outside door a crack.

A very short man stood in the corridor. His hands were cupped in front of him, obscuring something. “Yes?” I said.

He uncovered his hand and held it out to me. In his palm rested an egg. “Welcome,” he said in English. He did not smile.

“Thank you,” I said, looking from the egg to his somber face.

“I don’t speak English,” he said in English. We switched to Russian. His name was Hussein, from Morocco. He’d brought me a hard-boiled egg as a housewarming present.

“Are you a student here?” I asked him.

“Yes,” he said, “I study philology.”

“Stamp collecting?” I squinted at him, trying to decode the unfamiliar word.

“No,” he said, “Philology. If you are in this building, you also study philology. This is Moscow State’s philology dorm.”

“Oh,” I said, “OK. Philology.” We stared at each other in silence.

“Well,” he said finally, “Enjoy your stay.”

Feeling like I’d failed a test, I closed the door, went back in my room, and opened my dictionary. “Philology, philology.” I flipped through the pages, curious to know what I was doing in this building. There it was: филология. The Cyrillic characters spidered across the page. And next to it, the English equivalent: philology.

“So,” I thought, “enrolling in that language class means I’m a philologist. A Russian philologist.” That sounded like something I’d enjoy telling people. Buoyed by this, and by the gift of the egg, I returned to the window and looked down at the pond. The swimmers were gone, the rectangle they’d cut crusting over with snow.

Pay Stove

I took one of the condoms out of the bag on my desk and slipped it into the pocket of my jeans. This building had 28 stories and four colossal wings. It was huge; the Death Star of dormitories. There had to be a place here to at least find tea.

I tied my boots and stepped out into the dark hallway. Hussein’s footprints were visible in the dust on the wooden floor. I followed them right across the hall to his door. Afraid to disturb him, I listened. Nothing. No sound at all. I turned away and headed down the long brown corridor. I was looking for a cafeteria, or a vending machine. Anything.

I turned a corner and stopped as a door ahead of me opened and an old woman stepped out into the gloom of the corridor. She closed the door behind her quietly and walked in the opposite direction. She was holding a pot, so I followed her. I shadowed her around another corner and halfway down the next corridor, where she turned left into an open doorway. I waited a few moments and followed her in.

The kitchen was a long, narrow room, lined on one side with a row of big windows that provided the only light. On the other side were two decrepit gas stoves. They listed together, holding each other up like drunks. A utility sink sat against the back wall. The old woman stood at the sink, scrubbing her pot. She looked over her shoulder at me, startled, as I stepped in the room.

“Excuse me,” I said, smiling a big friendly smile, “Is there anywhere in this building to find tea?”

She looked at me like she thought I might be deranged. “If you want tea, you’ll have to boil water.”

“Oh,” I said, “Right.”

“Do you have a pot?”

“No.” I felt accused; defensive. “It’s not my fault my suitcase disappeared,” I wanted to say. “I brought a pot to Moscow with me; of course I did. I’m not an idiot.”

“Ladno,” said the old lady, “you can use mine.”

She stepped toward me, holding out the dented aluminum pot. I took it and moved around her to the sink. She was really quite old, I noticed. Eighty, maybe even older. And she was wearing an apron, and slippers. What was she doing in Moscow State’s dormitory? Was she a philology student too?

I decided not to ask, and put the pot on a burner. The stove was so lopsided that I had to hold the pot level to keep water from spilling over the lip. The knobs to turn on the gas were missing from both stoves. I tried to turn the notched metal stem where the dial controlling my burner had been, but it wouldn’t move. I pressed it into the stove and tried again, still with no luck. I tried the other three stems, then moved to the other stove. None of them would turn. I held the pot out in front of me, staring at the stoves.

“You need a kopeck.” The old woman spoke up from behind me. “Do you not have a kopeck?”

“Well, no.”

“No pot and no kopeck. Where are you from, devushka?”

“Florida,” I said.

“Of course!” she replied, satisfied. She reached into the pocket of her apron and withdrew a tiny coin. I took it from her, ashamed, and turned back to the stoves.

“Where do you put it in?” I asked.

“What?” she stepped up beside me, frowning.

“This is a pay stove?”

“A pay stove!” she cackled, “Girl, give me the kopeck.” She plucked the coin from my fingers and deftly inserted it into the groove in one of the stems on the front of the stove. Turned it to the right, and one of the burners flared to life.

“It’s a Russian invention,” she said, “A pay stove.” The kopeck disappeared back into her pocket and she turned to go.

“What room are you in?” I called out. “So I can return your pot.”

“Keep the pot. This is my gift to you.”

I thanked her and turned back to the stove. I held the pot level over the burner, relieved to have a project underway. Only then did I remember that I had no tea. Or cup. I decided to forge ahead anyway. I’d worked so hard to get to this point. I looked into the water, which hadn’t started boiling yet. The handle of the aluminum pot was getting uncomfortably warm. I opened and closed my fingers around the handle, shifting around the pot and trying to work my other hand under my shirt so I could use it as a potholder. The pot wobbled on the burner, spilling half of the water and extinguishing the flame. The gas continued to hiss out. Without a kopeck, there was no way to turn it off.

I remembered the night before, when I’d arrived in Moscow. In the middle of the night, unable to sleep from jet lag, I’d opened the window that took up most of one wall and sat on the sill with my legs dangling out. I sat and smoked, watching Moscow appear and disappear behind blowing sheets of snow. Twenty-three stories below, a van crept through the empty streets, gray megaphones bristling from its roof. A cloud of noise traveled with the van, a man’s voice repeating something as it progressed from street to street. When it finally passed by my building, the message floated up to me.

“Emergency!” said the man in the van, “There is a gas leak! Everyone must extinguish their cigarettes now!”

“Is that what happened last night?” I wondered now, as the gas shushed out of the stove and sweetened the air around me. “Some girl without a kopeck blew up a building?”

I opened one of the windows and went to find the old lady.

***

Her own dusty footprints led me straight to her door. I knocked and it was immediately opened by a boy about four years old. “Um, do you have a kopeck?” I asked him.

“Baba!” he yelled over his shoulder, “The American girl wants another kopeck!”

“Sasha! Close the door!” a young woman yelled back in a sharp voice.

“But Mom!” he said, turning all the way around and letting the door swing wide open. Inside, six pairs of different-sized shoes lined a short entry hall. In the small room beyond a young man and woman sat together on a brown couch, both of them staring at me. A card table and two folding chairs were pushed against the window, and on a corner of the bed sat the old woman, a toddler perched on her lap.

“Sasha!” The young woman sprang to her feet. She dashed toward us, pushing the boy behind her as she backed me into the hallway. She closed the door and looked at me, breathing hard. “Yes, yes, okay!” She jammed her hand into her jeans pocket and yanked out a coin, which she thrust towards me. “Now leave us alone!”

She stood in the hallway watching me as I hurried back to the kitchen.

I turned off the gas, my face burning. My ineptitude had cost money for a family so desperate they had to live in a dorm room. It was humiliating for everybody. I poured the water into the sink and closed the window.

I walked back down the hall the way I’d come. When I reached the family’s door, closed now against the outside, I stopped and put down the pot. The kopeck stayed in my pocket.

Read the next chapter here, and subscribe so you don’t miss out.

RIP

I would like to pay respect to those we lose along the way. If there is someone you would like to be remembered in future newsletters, please post links to their obituaries in the comments section or email me. Thank you.

How we’re getting through this

Making this.

Learning Deborah Roberts’ name.

Taking leadership lessons from Jacinda Arden.

Learning which TV ads are performing better now.

Valuing how stores treat employees as much as whether they’re fully stocked.

What I’m reading

E.B.’s excellent look at why Texas wasn’t better prepared despite being warned.

Polling on what people think should be prioritized right now, health or economy.

Dan Zak’s lovely review of Alec Baldwin’s memoir.

C.T. explaining the oil crisis.

Got some reading suggestions? Post them in the comments section, and I might include them in the next newsletter. Have a book to promote? Let me know in the comments or email me.

What I’m watching

Phoebe Waller-Bridge is airing her one-woman stage version of Fleabag on Amazon Prime to raise money for COVID-19. She’s winning and charismatic, but it’s clearly an early iteration. The television show—and the second season in particular—is still up there with the best storytelling I’ve ever seen.

S.N.V. is rewatching Scrubs. The musical episode holds up.

Got suggestions? Post them in the comments section, and I might include them in the next newsletter.

What I’m listening to

Tears for Fears’ Curt Smith and daughter play the Donnie Darko version “Mad World.”

Have you joined Walker Lukens’ Monthly Record Subscription Club yet? I would like to build an entire industry to elevate Walker’s talent, largely but not solely because of my deep love for his song, “Don’t Wanna Be Lonely (Don’t Wanna Leave You Alone,” which the FDA has classified as a sanctioned mood elevator. Fun fact, in the video below, the long-haired guitar player is Walker’s drummer and best friend, Zac, and the girl he’s not getting along with his Walker’s backup singer and keyboardist and girlfriend, McKenzie.

Got suggestions? Post them in the comments section, and I might include them in the next newsletter.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.