Happily Ever Now

Here is what it's like for a boy to love something for so long, and then for that love to be returned to him as a man publicly, ecstatically, and joyfully. With mooing.

This is the always free, reader-supported weekend edition of The Experiment, your official hopepunk newsletter. If you’d like to support my work, become a paid subscriber or check out the options below. But even if you don’t, this bugga free. Thanks for reading!

I’m going to tell you right off the bat—no pun intended—this is a love story. It began when Jason Benowitz was a little boy, about three or four. His dad would snag the company seats along the third baseline to see the Baltimore Orioles and their star Cal Ripken Jr. Every time he came up to bat, the stadium would erupt in flashes going off. Under the lights, a ballpark can look pretty grand to anyone, but to little Jason, those flashes made it seem magical.

Cal retired when Jason was in elementary school, but Jason kept it up, watching games on the television with his grandma and mom. He wore an Orioles jersey every year for school pictures even though the Orioles spent a lost decade in mediocrity. He kept the faith when the Washington Nationals started up down the road when he was 12, stealing away many of his friends in Gaithersburg, Maryland. “When the Nationals came to town, it felt like I was on the sinking ship by myself,” he says.

His metaphor was apt. In 2001, Sports Illustrated ran a headline saying the “once-proud Orioles have become the laughingstock of baseball—the worst may be yet to come.” And come it did in the form of a federal investigation that found the Orioles cheated more in the steroid era than any other team—and still lost. A lot. It was a rebuilding phase that lasted a decade.

Jason kept the faith. It sounds like a religious practice when he explains his routine. He crammed his high school schedule with as much band credits as possible, and after school he’d come home and watch the Orioles play. He says the whole thing taught him patience. “Baseball had become the thing I did to enjoy and escape,” he says. “All that to say, it makes it a little tough when the thing you enjoy the most is not the most enjoyable to watch.”

Towards the end of that decade, the Orioles traded away their best pitcher to the Mariners for three players one of whom was a hotshot prospect named Adam Jones. Right away he was different. He moved to Baltimore and embraced the community and injected a playful joy into a dour clubhouse. Most of all, though, he made it clear he expected to win. I remember how much that shocked me, and I realized how much I had internalized losing as a lifelong Orioles fan.

The Orioles were good then, briefly. From 2012-2016, the Orioles had the highest winning percentage in baseball. By now Jason Benowitz was old enough to buy a beer at the ballpark, so that was pretty great. But the Orioles were always playing way above their projections. They were ignoring the data revolution taking over the sport and not scouting in Latin America at all. It felt like the Orioles were getting lucky. “As much as I loved it, you knew it was finite. It was gonna end,” says Jason.

And then it did. The Orioles started the 2018 season hoping to make the playoffs, but they played so badly so often that after only 35 games Sports Illustrated was calling them the “saddest team in sports” in what did not to me seem exaggerated at all. Something about the Orioles seemed to inspire the magazine’s headline writers: “God Help the Baltimore Orioles, Who Must Trade Manny Machado and Blow It All Up.”

“saddest team in sports”

Jason kept the faith, telling friends when the Orioles traded Machado, “In today's baseball, if you don't have a $300 million payroll, you have to be bad to be good.” And by that he meant that the more games you lost, the better draft picks you got. And if you invested in scouting and developing players using data and modern training techniques—and making long-overdue forays into Latin America, then maybe a smaller-market team like the Orioles could compete with the likes of the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees.

But blowing it all up left a lot of rubble. “You were gonna lose for awhile,” says Jason, “but I just didn't know it was gonna be this bad.” From 2018-2021, no team in baseball lost as many games. In fact, no team had ever lost that many games over that many years. And as the losses piled up, Jason kept vigil, watching every game he could. “Oh, yeah. Religiously,” he says, adding, “I'll do you one better. The year that they blew it up is the year I got season tickets.”

Imagine Jason, then 25, sitting in his seat along with a few thousand others in a ballpark built to hold almost 46,000, watching a team intentionally designed to lose as many games as possible. “Their outfield was DJ Stewart, Keon Broxton, and Dwight Smith Jr.,” says Jason. “I mean, that was the outfield.” Don’t know who those players are? Exactly. Those players were so bad that when they called their dads after the game, their calls got sent to voice mail. But Jason kept showing up, getting his hot dog, fries, and a pretzel, watching his favorite team suck out loud, and on purpose.

“Biiiiiig Cowser guy”

The Orioles were building for the future, so that’s where Jason put his energy. If the beat writers reported that the Orioles were thinking about drafting a certain player, Jason poured over anything he could find. And that’s how, in 2021, he first encountered a 5-tool player for Sam Houston State University named Colton Cowser. Jason watched enough game tape to tell that Cowser could flat-out hit, but he didn’t really attach to the player until he learned that he, like Jason, loved building Legos. Once Colton started tearing up pitchers in the minors, Jason thought he’d make it official by adding this to his Twitter bio: “Biiiiiig Cowser guy.”

Colton quickly revealed himself as a bit of a goof. He didn’t pick up when the general manager called to tell him he’d been drafted. “I was told not to answer if I don’t know the number,” he said. While in the minors, he started a Lego-building competition with a teammate that is now in year three. His biggest regret as a professional baseball player? That was in AAA when Star Wars Day was rained out and he didn’t get to wear the cool Darth Vader-themed jersey. In the old days, we would have called him a flake.

In 2022, the Orioles held a fan event where people could take batting practice, shag fly balls, throw pitches, or get autographs from minor league players no one has ever heard of, one of whom, of course, was Colton Cowser. Jason, of course, got there early before the crowds and made a beeline for Colton. “I talked to him about Lego,” says Jason, “and showed him some pictures of mine, the stuff I've built.”

I feel an urge to condescend at this point. How cute, I say. What a nerd, says my less-generous self. I know that voice. It protected me a long time when it wasn’t safe to show my open heart to other people, to love unashamed. I am learning to reassure that voice that while I appreciate all it has done for me I am safe now. How great is it that Jason went up to this brilliant athlete and said, in effect, I’m like you are in this other, fun way that makes you interesting to me. I am trying to be more like this Jason. I thought about making this paragraph a footnote, but this essay isn’t about baseball, remember. It’s a love story.

In Spring Training last season, Colton established himself as the team’s chaos muppet. He heckled players when they posed for publicity shots. He interrupted an interview of Adley Rutschman, the team’s highest-profile player, by asking about his date with a starlet that, of course, never happened. At one point, he bought jewel-toned velour jumpsuits and ‘80s New Wave sunglasses in hopes that he could convince his teammates to wear them to work one day.

On August 24, 2023, he did. Unfortunately, that was the high point of his season. He played, badly, in 26 games before he was sent back down to the Minor Leagues, and no one thought it was a bad idea. If his body language spoke English, it would have gotten in trouble for swearing.

And as Colton’s self-appointed hype man, Jason got tagged online every time Colton failed, which happened a lot in 2023. Jason doesn’t want to admit that Colton’s lack of success and the resulting online harassment hurt, but “being publicly out for this guy, you have to live and die with it, because there were a lot of people who were willing to let me die with it.” Mainly, though, Jason felt bad for Colton.

Still, Jason worked hard to stay positive, especially online. A production manager for a church, Jason sees his fandom as an extension of his Christianity. “I feel like my job is, especially online with everything, to love people. When it comes to baseball, my job is to love people through 280 characters,” says Jason.

In March of this year, Jason went down to Sarasota to visit his grandmother and catch some Orioles spring training games. Right away he saw a change in Colton. He’d made a mechanical change to his batting stance, but the biggest change he saw was his confidence. Colton hit a home run in the first game Jason attended. As Colton rounded third, Jason could see he was laughing. Colton was having fun again.

Colton made the team out of spring training, which meant he was going to get to be introduced running down a big orange carpet through the outfield on opening day. Online, fans started to get excited about “mooing” for him. You know, Cowser-cow-moo. Others worried that he would mistake the moos for boos and get his feelings hurt. (Let me pause here to note how sweet the Orioles Twitter community is on the whole.) As the acknowledged Biiiiiig Cowser guy, Jason got Cowser’s permission through an intermediary, and when he jogged down that carpet, the moos rained down on a smiling Colton.

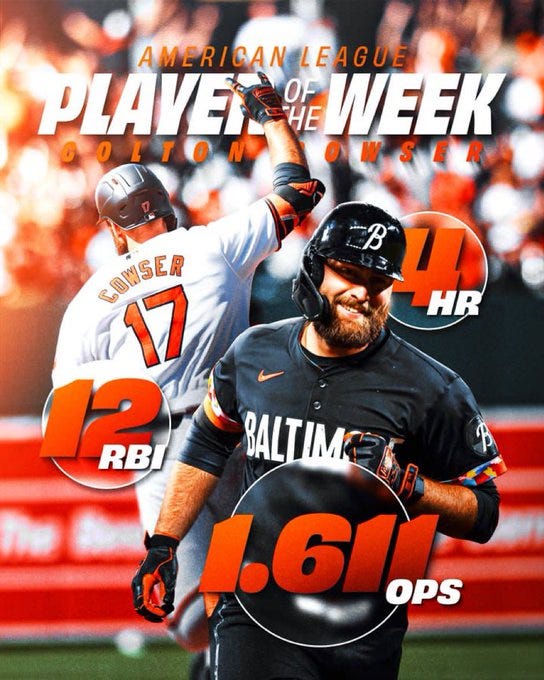

After delivering four home runs in four games, Colton had won both a nickname—the Milkman (he delivers, get it?)—and the American League Player of the Week award.

And every time Colton did anything good, which by now was all the time, Jason would get tagged online. All of a sudden, Twitter had become too positive for Jason, who was tagged so much he had to turn off his mentions. “It was quite literally draining my phone battery,” he says. But still, it felt kinda good. “It was one of the coolest things for people to say, we know this is your guy, so let's celebrate that.”

A late-April game against the Kansas City Royals was interrupted by a five-hour rain delay. Most of the crowd left. Not Jason. This guy sat through the 2000s. He has the patience of a monk, so he was still there when James McCann hit a walk-off home run to win it. Jason posted a video of him wordlessly gesturing at the fireworks in disbelief, and that tweet earned him a new follower, former Oriole centerfielder Adam Jones.

“Keep being positive my guy. Too much negativity around and on social media” messaged Jones, who suggested they get together for a beer when he was in town. Jason didn’t take it seriously. “I didn't think anything of it,” said Jason, but in early May Jones reached out again, suggesting they meet up at Boog’s BBQ, the barbecue stand at Camden Yards run by Boog Powell, the former Oriole first baseman.

Jason figures he’s just grabbing barbecue with his new Twitter buddy, which would have been great. But after a couple of other friends meet them, Jones says to Jason, “We're gonna hang out” and starts walking.

“I had no clue where we were going, and we get on this elevator and find ourselves in the suite,” says Jason, still dazed at the experience of drinking Simply AJ Ballpark IPAs with their namesake. He even got caught on the game broadcast.

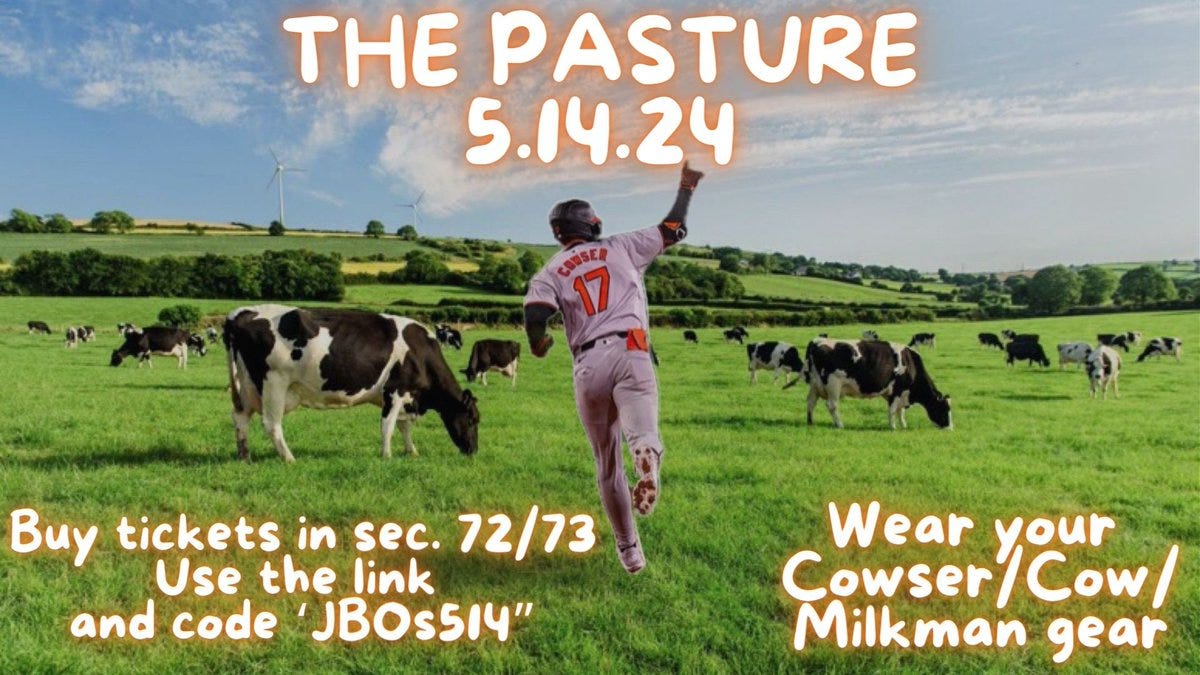

That same day, Jason announced a big project he and a few others had cooked up: The Pasture. By then, Colton had won the American League Rookie of the Month and become the Orioles’ everyday left-fielder while winning over fans with his impish humor. More and more fans were showing up every day dressed as milkmen and as cows.

“Cowmania has swept Camden Yards,” declared the Baltimore Banner.

Wouldn’t it be cool, Jason thought, if all of Cowser’s fans could all sit together in a section in left field? His season-ticket representative agreed, and on Tuesday there will be a lot of mooing in Section 72 at the ballpark.

His role in all this is bringing him a lot more attention than he’s used to. Orioles radio play-by-play announcer Melanie Newman mentioned him on a broadcast. MLB did a whole story about him the other day. And yes, in case you’re wondering, Cowser knows about the Pasture and that it was organized by the fan who talked to him about Legos way back then.

After so long in the wilderness, Jason feels the moment. “I truly love this community & everything it’s building. I am genuinely overwhelmed and don’t have many other words,” he posted online.

But this isn’t about him, Jason wants to add. This is about arriving at this moment when a team you have loved starts loving you back in earnest. This is about feeling secure that it’s not going to go away in an instant. This is about Jason trying to allow himself to enjoy this moment to its fullest potential.

“Being 30 years old, I’ve been shaking a soda bottle for 27, 28 years, and now I can finally let the cap off. You don't know what’s gonna come out, but you know there’s going to be an explosion,” he says. “That’s what it feels like. I’ve waited so long for this. I’ve been patient, I’ve been trying to keep other people patient. The thing that has brought me the most joy, even through their dark days, now is just pure joy.”

This is a love story about allowing yourself to feel all of that fizzy, explosive love and live happily ever now. Moo.

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Threads at @jasonstanford, or email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

Joy in Mudville

Ain't the Beer Cold!

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is out in paperback now!