By the time you read this, Heather Linington-Noble will be out of surgery

She just hopes the Baltimore Orioles keep winning

Welcome to the always free, reader-supported weekend edition of The Experiment. If you’d like to support my work, there are links to do so at the bottom, or become a paid subscriber. But this week I want you to support the woman I’m writing about, Heather Linington-Noble, the queen of Orioles Twitter.

Heather Linington-Noble loved getting participation trophies as a kid. “I played so many sports growing up and was terrible at all of them,” she said. “And I got a whole bunch of participation trophies. I loved those participation trophies.” Her parents never made her feel like a failure. Instead, they taught her “it’s a good thing that you're just doing this. And I think that I transitioned that into my sports fandom.”

It’s not like Heather doesn’t prefer that the Baltimore Orioles, the team she grew up rooting for, wins. “But it’s not the primary reason why I watch baseball. I watch baseball ‘cause I like the sport and I like the players.” This attitude served her well when the Orioles started getting losing seasons at Costco. Rooting for a team that loses more than 100 games a year tests your love of the game, but Heather stuck with her boys. “I enjoy going to games whether the team wins or loses, especially when they always cultivate this really great, fun group of guys. Like, even when they were bad, the players themselves were easy to root for.”

After two consecutive losing seasons, the Orioles hired Mark Elias and Sig Mejdal to rebuild the Orioles. Elias, a Yale graduate, and Mejdal, who dealt blackjack in Reno before working for NASA, inherited a team with no prospects, metaphorical or tangible, no presence in Latin America, and no hope of winning. But Elias and Mejdal had been lured away from the Houston Astros where they had helped pioneer a new way to win that relied on using data to identify and develop good players.

“Even when they were bad, the players themselves were easy to root for.”

This wasn’t Moneyball as depicted first in the Michael Lewis book and later in the Brad Pitt movie. Moneyball was about finding inefficiencies in the pricing of baseball players, i.e., hidden bargains. This new way of winning, as shown in The MVP Machine: How Baseball's New Nonconformists Are Using Data to Build Better Players by Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik and Astroball: The New Way to Win It All by Ben Reiter, used data — and new training techniques and technologically advanced equipment — to unlock every player’s potential to improve.

Remember, this was 2018. The Astros had just won the World Series, and it would be a couple more years before their cheating would be exposed. (Elias and Mejdal would later be found to have no connection to the cheating.) Heather knew that Elias’ hiring meant that the Orioles would follow the Astros model. First, they would trade away all their good players to stockpile talent for better days in the future. And as a consequence, because they would be fielding absolutely trashmatic teams, they would getting better draft picks, giving them better chances to pick the best players from the amateur ranks.

Orioles fans would have to learn to hope for better days. Elias hired Brandon Hyde, a 40-something manager with a fatherly smile, and told him not to worry about the wins and losses. “It’s much like, when we have a minor-league manager, the wins and losses are pretty incidental,” Elias said. “You’re trying to have an environment that’s conducive to making players get better.”

And then Elias did something that would later change everything: He drafted Adley Rutschman, the All-American catcher from Oregon State University. There was no debate that Adley should have been picked first, but even as skilled as he was, there was something else he was bringing to the table, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

“You’re trying to have an environment that’s conducive to making players get better.”

Heather didn’t go into fan hibernation during the Orioles long string of losing seasons. “One of the great things about them is that they're really good at giving fans access,” she said. You know those people who always show up to speak at city council or school board meetings? That was Heather, except she didn’t show up to complain. She first met Elias at an off-season event for the fans called the Winter Warmup and discovered in 2019 that he had seats next to her friend in the eighth row behind home plate.

“There have been like six or seven times over the last few seasons, maybe more where Elias has come and sat next to us during games,” she said. “And I've just been like, ‘Hey, what's up?’” The first time that happened was in 2021 when the Astros were beating the Orioles “23-2 or something like that. His former team, of course. And he’s sitting there next to us, just like shaking his head and whatnot. It was a kind of surreal experience.”

Heather thought Elias seemed like a nice guy with a snarky sense of humor, and when she read Astroball, she was struck by their belief that far from being data-driven automatons, “winning teams have good team chemistry.” Early on, she figured out that Elias was building a positive culture from which winning teams would grow.

“Winning teams have good team chemistry.”

Twitter on a good day is a bad place, and during the fallow period Orioles Twitter was unrelentingly negative, with one exception: Heather Linington-Noble. She celebrated the rare victories and refused to contribute to the daily second-guessing of every lineup Hyde turned in. She even started a podcast that “focused on the bottom-dweller teams to give some positive spin on those seasons. So it focused on the Orioles and the Rangers and the Mariners and the Tigers,” said Heather, who began to get a reputation as a bright spot on Orioles Twitter.

The Orioles have a partnership with the Guinness Brewery where players guest bartend. “You can go and just hang out and talk to them,” said Heather, who remembers one time when Tyler Wells, a six-foot-eight pitcher, was bartending. “I got up to the bar, and he comes up to me and he’s just like, ‘You're Heather, right?’ I was flabbergasted. I was like, Why do you know my name?”

“I think a lot of people do not realize that those of us who are active on Twitter, the players know who all of us are,” said Heather, who says players and their families came to trust her as a safe space. They told her that they’ll search for their names and see what fans say about them. If you have a beer with a player’s wife, it’s hard to call her husband a flaming bag of poo if he has a bad game, so Heather stayed positive.

“You're Heather, right?”

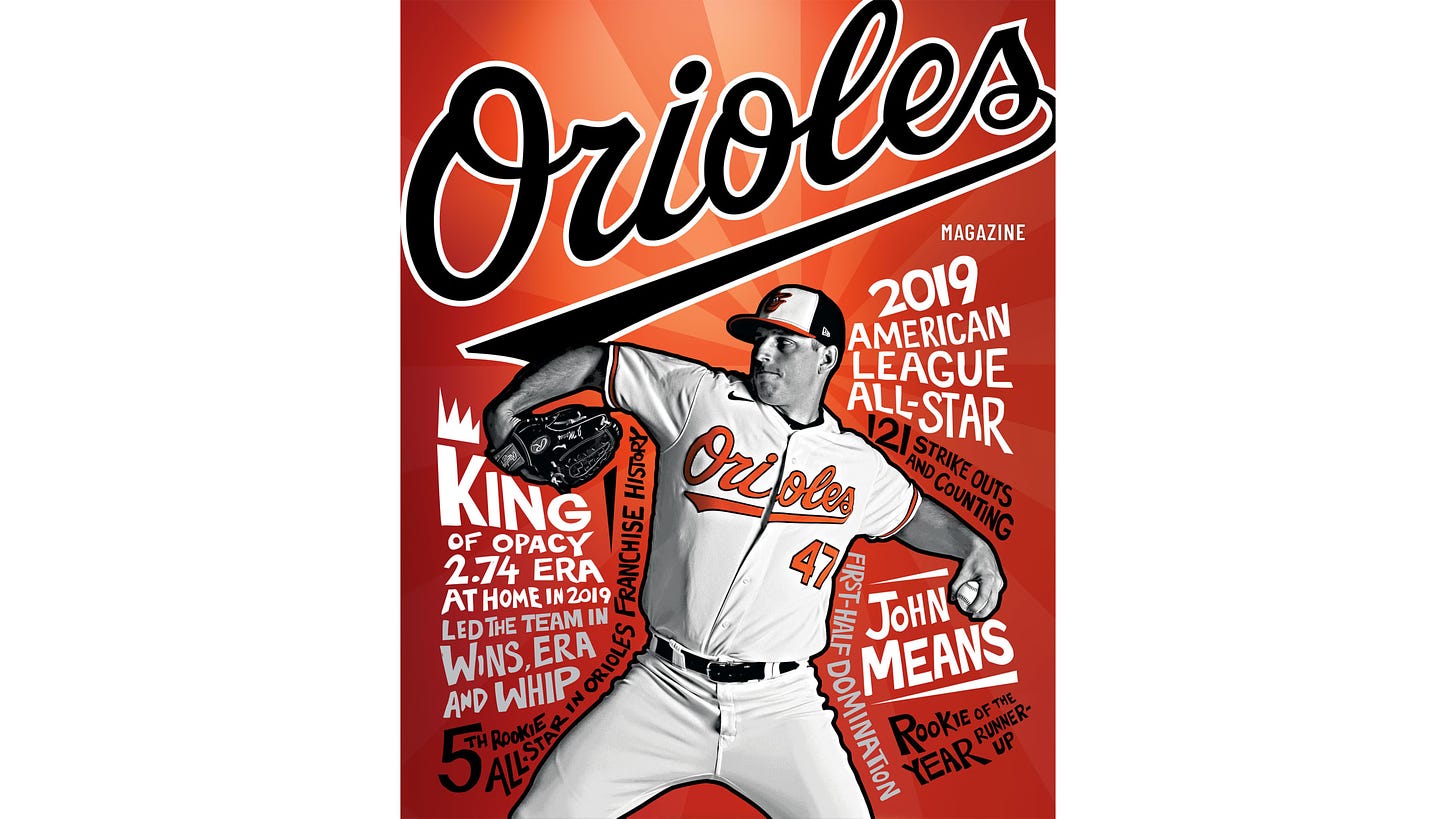

It was at an off-season fan hangout before the 2019 season that Heather met Caroline and John Means. John, is a left-handed pitcher that most thought would be cut before the season after being called up in 2018 as cannon fodder in a 19-3 loss to the Red Sox. Heck, Means thought he would be cut, too, so much so that he made a LinkedIn page because he figured that’s what you needed to get a real job. It had two entries: professional baseball player and substitute teacher in DeSoto, Kansas.

But Means didn’t just hope things were going to work out. In the offseason, he went to one of the data-driven coaching facilities where a new breed of coaches were introducing new training methods such as throwing weighted balls to build strength. At the end of the 2018 season, his fastball was about 91 miles an hour, which is fast if you’re driving but not if you’re pitching in the Major Leagues. When he showed up at spring training in 2019, his fastball was over 93 miles an hour, fast enough to make his slower pitches more deceptive. Suddenly, thanks to new-fangled methods of player development, this one-time substitute teacher had to put another entry on his LinkedIn page: 2019 All-Star.

“He and Caroline are the nicest people, and they love this team so much,” said Heather.

In 2021, the Orioles began to show signs of life. One outfielder, Cedric Mullins, hit 30 homers and stole 30 bases, a rarity. A rookie first baseman named Ryan Mountcastle, whom Heather called a “himbo who was like a golden retriever who would got reincarnated into human form,” hit 33 home runs. Means even threw a no-hitter. Elias promised that the next season the Orioles were going to be “interesting,” and in 2023 they’d be competitive. “And it turned out he was right,” said Heather.

Three things happened in 2022 that made them interesting. They rose from god-awful to mediocrity, winning barely more than they lost. Means got injured and required a surgery that takes a year and a half to recover from. And the third and most-important thing to happen in 2022 was that Adley Rutschman, the All-American from Oregon State, came up to the majors.

It is not too much to say that he has changed everything.

“I think that he's been, regardless of his on-field performance, which he's been very good, he’s been an excellent player who just changed the team for the positive in a hugely tangible way. And, you know, he’s the absolute nicest guy, and he’s so genuine.”

“Adley has changed the team for the positive in a hugely tangible way.”

The most-obvious manifestation of Adley’s impact on the team culture is the hugging. When a pitcher leaves the mound after getting three outs, Adley will run up to the foul line to greet him with a glove tap. And at the end of the game, if the Orioles win, Adley will jog up to the pitcher, touch gloves, and then hug — but for real.

At first, national baseball writers didn’t know what to make of this. There is, comparatively, a lot more crying in baseball than there is hugging. Catchers never hug their pitchers, much less with obvious affection and apparent joy. But Adley just kept hugging despite the doubters, and now the other Orioles catcher, a veteran named James McCann who was traded from the Mets, hugs pitchers, too. And it’s not just the catchers anymore.

“It's the most hugging that I've ever seen any team do. They're hugging each other all the time,” said Heather. “It’s delightful.”

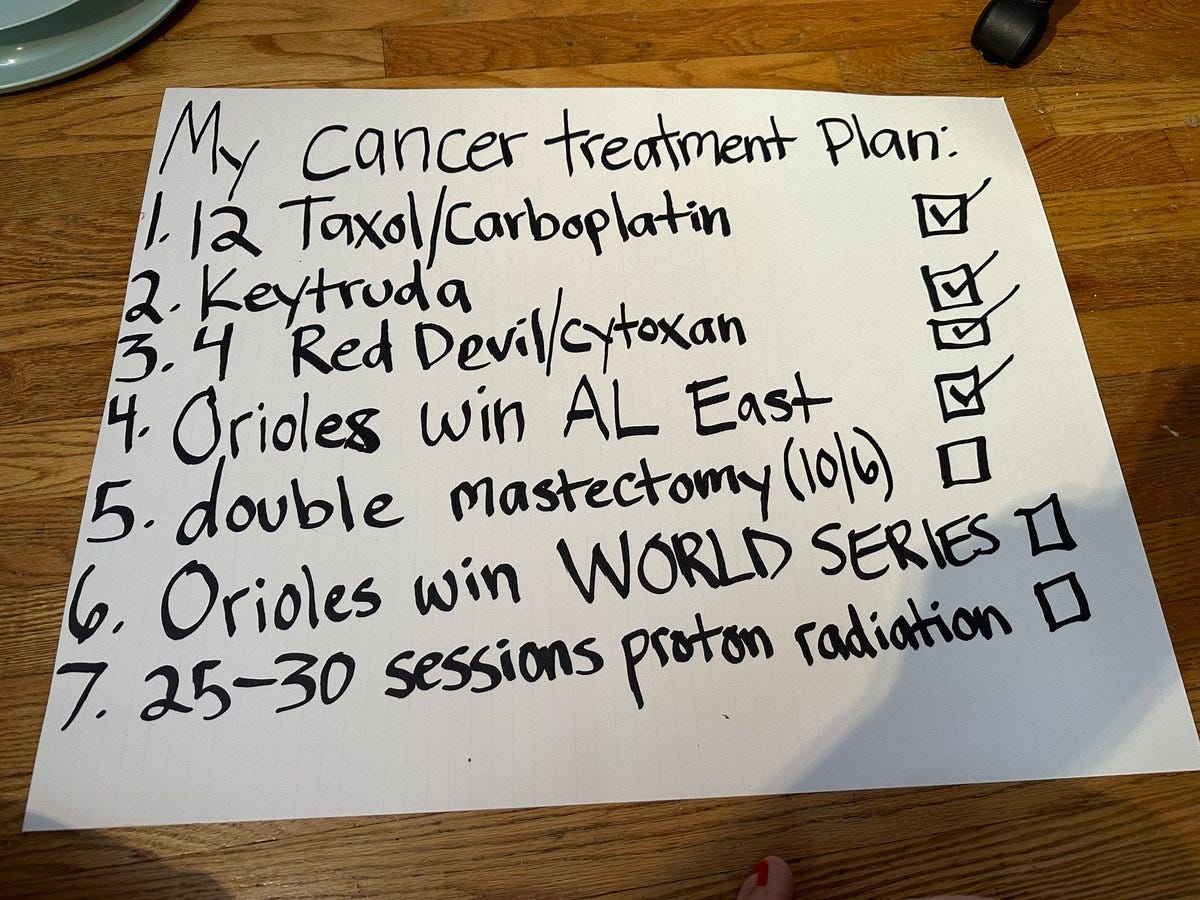

Heather felt a lump toward the end of 2022 and was diagnosed with breast cancer during spring training 2023. “I was really optimistic,” she said, speaking of the Orioles prospects, not her cancer. The same national baseball writers who doubted Adley’s hugging now predicted that the Orioles would regress. After all, every team that had improved as much as the Orioles did in 2022 had fallen back down to earth.

But as Heather quit her job to focus on her treatment, the Orioles kept winning, and they kept doing so in a way that I’m not used to seeing grown men act in public.

“Do you think it's too much to say that [Adley] has made love a part of the experience of rooting for the Orioles?” I asked Heather.

“Not at all. Not at all,” she answered. “They’re all about having fun. They’re all about loving each other.”

“To see guys truly love each other, guys truly pull for each other, that’s part of why you see the guys having the success they are,” said McCann. “There’s something special here.”

“It's the most hugging that I've ever seen any team do.”

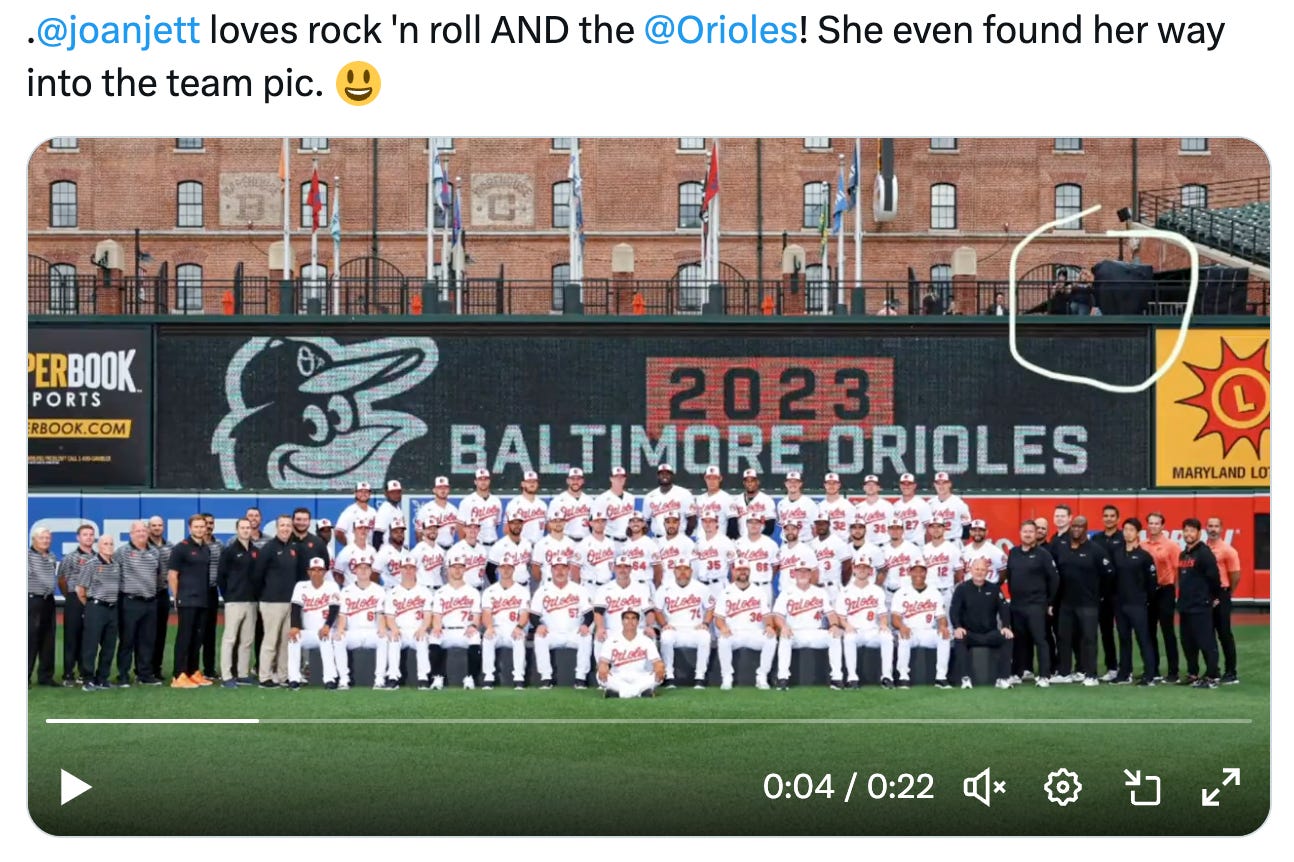

You don’t often hear baseball players talk about how much they love each other. But this team is different. The vibes this season have been immaculate. There is the homer hose (Do not call it the “dong bong”) that players drink water from after hitting home runs. That led to the splash zone where fans get hosed down by Mr. Splash when the Orioles hit an extra-base hit, score, or if Mr. Splash just feels like it. This Orioles season is so magical Baltimore native Joan Jett dive-bombed the team picture before taking her band to the game.

The Orioles had learned to win. Since Adley came up to the majors, the Orioles have not been swept in a series. This is the longest any baseball team has gone without being swept since before Jackie Robinson integrated the sport. And this season they have succeeded in the toughest spots more than any other team, rallying for more wins and hitting the best in high-pressure situations. “I think the most important thing to know about this team is that they believe in themselves,” said Heather.

The Orioles fan base — and Orioles Twitter in particular — had not learned how to win. “They would go in spirals every time the Orioles lost a game or gave up a run,” said Heather, “but the Orioles themselves, this team, the team itself, they never did that. They never spiraled. They always went out believing that they could win every single game that they played. And they think that they can win the World Series.”

And because Heather knew these players and had drank beers with them, she knew that. And as the 2023 season progressed, Heather was among the few on Orioles Twitter pointing out that the Orioles were not one injury away from ignominy. One bad week didn’t mean a return to the Dark Ages of 100-loss seasons. Keep in mind, Heather was living her cancer diagnosis out loud online. Being scolded for your silly fatalism by a lady dealing with cancer proved remarkably effective.

“The most important thing to know what about this team is that they believe in themselves.”

Heather went to the Saturday night game in September against the Rays on her own — along with 36,000 of her best friends. You know the game. Grayson Rodriguez pitched eight shutout innings to end a four-game losing streak, Gunnar Henderson had a home run, and Heather ran into Caroline Means, John’s wife, on Eutaw Street. “She is with her mom and John’s mom and introduces me to both of them,” said Heather. “And her mom and her mother-in-law start talking about how I am, like, such a great, positive fan. And I was like, What?”

Heather also went to the last win of the season on the last Saturday night in September. “I was just sitting there in my seat, and I feel a tap on my shoulder, and it’s the ball girl,” said Heather. “And she says, you’re Heather, right? I follow you on Twitter.” Apparently the ball girl gets to pick who throws out the first pitch, and she asked Heather if she would like to do it.

The scoreboard identified her as a “randomly selected awesome Orioles fan” when she was introduced. She twirled for the crowd, waking them up by waving with both hands. Standing well in front of the mound, she threw the pitch off-target to the Oriole mascot. “I did not bounce it,” she said. “When I walked out that night, I had a whole bunch of people stop and tell me that I did a really good job.” And by the way, Caroline Means had John, who had finally recovered from his injury, sign the ball for her.

Heather’s double mastectomy took place early on Friday morning. By the time you read this she’ll be out of surgery, but you won’t see her at the ballpark for the first game of the Orioles’ American League Division Series against the Texas Rangers. When she talks about the surgery, it’s the missed games, and not the body parts, that she’s focused on. We were talking about how the recovery would prevent her from going to the games on Saturday and Sunday, and I asked how she felt about that, not specifying that I meant the surgery. “They better make it to the [next round of the playoffs] so that I can go to post-season games,” she said.

I get to see the Orioles play the Rangers on Tuesday in Arlington. John Means, who looks as good as he did when he was an All-Star, will* be pitching. Heather will be watching the game at home with her cats and doting husband. She’s rooting for them to make it past the Rangers into the American League Championship Series and from there to the World Series, which is the next step on her recovery before 25-30 sessions of proton radiation.

Please don’t joke about the super powers she’ll game from the radiation. I’ve already told that joke to her, and I can report that it got at best a courtesy chuckle. What Heather needs right now, other than an Orioles World Series trophy, is financial help. Surviving cancer is not a poor man’s game. You can sign up for her meal train, contribute Hilton points for her post-op recovery, get something off her Amazon wishlist, or give her money.

Heather has been a source of support for the Orioles when encouragement was harder to come by than wins, and this year she’s dragged Orioles Twitter into the light so we can truly enjoy this rarest of things, a magical season. As you are reading this, right now, Heather is recovering from a double mastectomy. Now is the time we need to return the love she has shown us and give her the support she needs. You won’t miss the money you donate to her, but you will regret not doing so if you don’t. Just like you’ll regret not enjoying this season while it’s still happening.

Let’s go O’s. And we love you, Heather.

* John Means will not be pitching. His elbow is sore, so he’s going to have to skip the series against the Rangers.

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!