In the beginning was Spring Training, a time sportswriters describe hackily as an eternally overflowing fountain of hope and optimism. For my Baltimore Orioles, not so much. Until last year, their streak of losing more than 100 games was broken in the last four years only by the plague-shortened season in 2020. Yay, COVID! And even though they achieved mediocrity in 2022, winning 83 out of 162 games, the experts gave the O’s a 10.4% chance of making the playoffs and a scant 0.3% chance of winning the World Series.

In the absence of optimism, the Orioles chose hope. In addition to a core of young players who had already made it to the major leagues, the Orioles had invited a shining group of prospects to work out with the big club. After years of being force fed shards of glass as an Orioles fan, this felt different. The players seemed… talented? They acted like they genuinely liked and were rooting for each other? What the hell?

“I can’t wait for this team to be awesome,” texted Jake last February.

“It’s like they have a whole ass World Series team in prospects and rookies,” I replied

“U coming up for a game this season?”

“I’ll do that,” I texted in more of an expression of intent than in commitment. Jake lived in Washington, DC, me of course in Dallas. I hired Jake as the first intern for a company I started in the late ‘90s in part because he was an Orioles fan. First, he became a protégé. I threw a party for his graduation from the University of Texas; he came to the hospital when my first son was born. At first, he called me for career advice. I went to his wedding, but he couldn’t make mine. We went to a ballgame in 2015 and made a point to see each other when we were in each other’s towns. We didn’t lose touch with each other as much as fail to maintain a relationship, but the Orioles, who had first connected us in the ‘90s now reconnected us over the possibility that they might soon not suck out loud. This is a story about that friendship.

Why the Orioles, you may fairly ask? I was nine years old. In 1979, dad took me to an Orioles game in Baltimore against the Yankees, whom I immediately learned were the enemy. Earl Weaver, the O’s famously irascible manager, got in a stemwinder with an umpire. Tippy Martinez (one of the all-time great baseball names) struck out Reggie Jackson. And Eddie Murray, the team’s star slugger, hit a ball that my eyes swore left the stadium entirely. It did not, but neither did I care. I fell in love hard that night. Later that year, I cried for the first time over sports when they lost the World Series to the “We Are Family” Pirates, my stepfather mocking me for both my tears and losing a dollar bet I’d made with him. The heartbreak cemented my devotion. The Orioles were mine forever. This is also a story about my devotion to the Baltimore Orioles.

About a decade ago, the Orioles were good, going to the playoffs one year, just missing it another. They were good in 2017 until all of a sudden they were strangely bad despite having good players. It was like pressing a button on your iPhone and nothing happens. Rooting for them felt inept and helpless. They fell apart completely the next season, and the team decided to burn the village in order to save it. Any player with any redeeming qualities was traded for prospects.

The theory was sound. The worse the team performed, the better their position in the amateur draft. If you stockpile enough good players in the minor leagues and infuse coaching with data analytics, then you could build a pipeline of good-to-great baseball players to fuel successive playoff runs at the mayor league level. In five years.

In the meantime, rooting for the Orioles would be an exercise in optional humiliation. You know how the song goes, “If they don’t win it’s a shame”? Rooting for the Orioles from 2017 until midway through 2022 was shameful. Partisans of other teams would mock me for sticking with them. Upon learning that I was an Orioles fan, one guy in a Blue Jays T-shirt thanked me for the batting practice. During this time, the Orioles were one of the worst teams in the history of the sport, and to stick with them required faith in things unseen.

I didn’t lose faith. In 2021, my best friend B.B. wanted to see a game, any game, so we went to Houston to see the Orioles play the Astros, one of the best teams in the league. Inexplicably, the Orioles won. Early the next season, S and I went to Los Angeles to see Ann at the Pasadena Playhouse. Coincidentally, the Orioles were in Anaheim. We went with my best friend from high school and his son. Mike Trout hit two home runs, but the Orioles won anyway, though they were still comfortably in last place.

Then they called up Adley Rutschman, a catcher who pretty much everyone in baseball agreed was That Guy. The Orioles started winning. In July, a road trip to play the Cubs coincided with a convention for me in Chicago. I packed my Orioles jersey and bought a ticket. If they won, the Orioles would be at .500, with as many wins as losses. You could call this mediocrity. I preferred to think that we would no longer be losers.

A side note to Orioles fandom. During the national anthem, when they sing “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave,” Orioles fans yell “O” not just at home but on the road as well. I was not alone in Chicago. Other fans had traveled to see the suddenly not-awful Orioles. During the national anthem, the shouted “O” was loud enough that Ryan McKenna, a reserve outfielder, broke protocol to turn around to see all the fans in orange and black. The Orioles manager, Brandon Hyde, said that is where he first noticed Orioles fans turning up on the road. I wasn’t the only one anymore. They won in Chicago and again later than season in Houston when I took my oldest son. By the end of 2022, I was wondering how far off being good must be.

Opening Day for the 2023 season found the Orioles in Boston. It was cold. Have you ever played baseball in the cold? Everything hurts, but that day nothing did. Adley got five hits in five at bats with a home run.

“This is fun!!” texted Jake.

“Oh Adley,” I texted. “I love that kid.”

The next day the Orioles were an out away from clinching a win when McKenna, who had been inserted for his defensive prowess, dropped a fly ball that would have ended the game. The Red Sox hit a game-winning home run on the next pitch. If you say the words “that fly ball” to an Orioles fan, even now, this is what they are thinking of. The memory still brings me a sharp pain in my left side under my rib cage.

“Oh my god this is the worst loss I’ve ever seen,” texted Jake. “McKenna literally dropped the third out. That was simply terrible.”

“I am in pain,” I replied. “That’s the kind of loss that will be hard to overcome.”

“Yes, that was literally terrible,” texted Jake.

“It hurts.”

“We are in shock here. It’s game 2,” he texted.

“I want Ryan McKenna to feel how angry we all are,” I texted. Jake liked that one.

“It hurts.”

There was no joy in Mudville because the happiness of game one’s triumph was stomped to bits the next day, setting an emotional pattern for the season. We had suffered for years on the promise that we would be good, but could we rely on the good if it could be so easily taken away by a single missed catch? We blamed McKenna for our lack of confidence that happiness was here to stay. Would our hope only lead to more pain?

The Orioles started winning and never really stopped. I saw two games in Arlington – both wins – and another with S and both boys in Minneapolis – also a win. And every game, Jake and I would text. The day after the Orioles lost a heartbreaker to the Yankees, they were losing again 5-1, and Jake and I were in our feelings. Adley, the catcher, made a practice of hugging the pitcher after the last out of a win. I was wearing my “Adley Hugs” T-shirt to coax a win out of my team, but I was not confident.

“I lost sleep last night,” I confessed.

“Lol,” he replied. “Me too. I hope we don’t get swept. This looks like one of those game where we get 3 hits total.”

“I am so pissed right now,” I replied.

“I’m moving onto tomorrow,” he texted. “It just feels like we are hacking right now.”

At which point, the Orioles put up eight runs in the seventh inning and ended up winning 9-6.

The next morning, Jake texted me at 7:46 a.m.

“I had a dream last night that we came back and beat the Yankees.”

“No. Way.”

The Orioles didn’t get swept then or ever, at least so far this season, and Jake and I kept texting each other. Thanks to the Orioles, he and I had developed a mutual emotional support society. Jake would usually demand that underperforming rookies be sent back down to the minors, and I would counsel patience and preach optimism. Often as not, I was right, because the Orioles kept winning. In July, they played the Tampa Bay Rays. The winner would take over first place in the division, but there was a problem.

“It appears my wife has conspired against me and invited friends over,” he texted. I would have to be his phone-a-friend while he pretended to entertain.

“I lost sleep last night.”

The Orioles jumped out to a 3-run lead. The Rays tied it in the 5th inning, which is when I started giving him regular updates.

“End 6. 4-3 thanks to O’Hearn homer.”

“Oddly, Rays only have 1 hit.”

“I’m nervous seeing this,” he texted unnecessarily. To be an Orioles fan is to know how easily being good can be taken away for no reason.

“Mid 7. 5-3.”

“Through 7. 5-3”

“Cano in for 8th.”

“End 8. Still 5-3.”

“Bottom of the 9th. Bautista in.”

A little later, Jake texts: “Give me good news.”

“Game over,” I text. “We are in first place.”

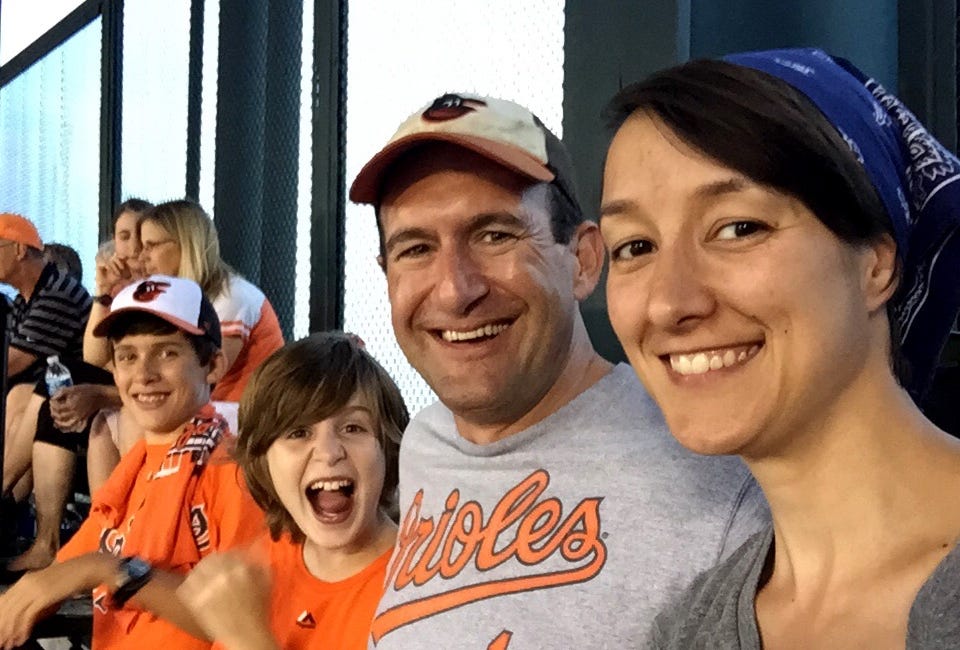

I told Sonia to get tickets to Baltimore. Jake and I were not going to go a whole season without watching a game together in person. It felt important.

We all met up — he with his 9-year-old son, me with S, by the Babe Ruth statue. We hugged without embarrassment and smiled without reservation. Do you know what it’s like to sit next to someone confident both in your friendship and in the outcome of the game?

I knew the Orioles would win as soon as I saw the picture of Adley and three other young stars-in-the-making arriving at the ballpark in velour jumpsuits, each a different color, and jokingly sci-fi sunglasses. Colton Cowser, the outfielder who wore the gold jumpsuit, scored twice, stole his first base, and had a thrilling outfield assist. Ryan Mountcastle, the first basemen in the purple suit, has been on fire since recovering from vertigo. “It's easier when you're just seeing one baseball instead of three.” Gunnar Henderson, the shortstop in blue, added a couple hits to the pile, and Adley the hugging catcher, who by now had achieved first-name status and was wearing pink, added a walk and an RBI.

“To see guys truly love each other, guys truly pull for each other, that’s part of why you see the guys having the success they are,” said James McCann, the backup catcher who came over from the Mets in the offseason. “It’s just a great place to show up every day to work. It’s not work when you love everything you’re doing. There’s something special here.”

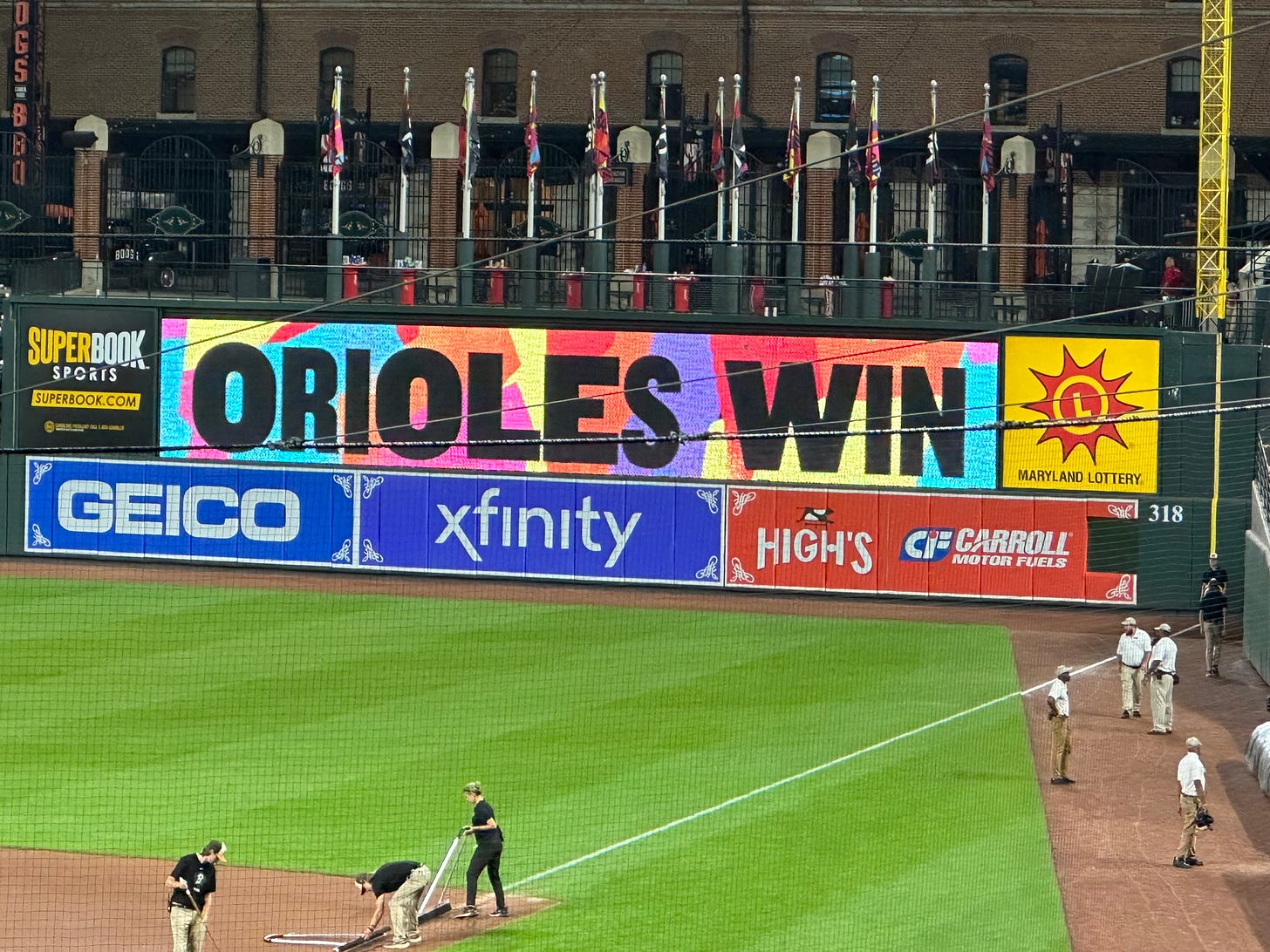

It's made even more special when they show up for work looking like futuristic Teletubbies. Was there any doubt they would win? It was a laugher, 10-3 over the Mets. The experts now give the Orioles 96.2% odds of making the playoffs. When the game was no longer in doubt, Jake and I made soft plans for me to come up again for the American League Championship Series if it got that far, maybe even the World Series, an idea that doesn’t seem incredibly ridiculous now. After the last out, “We Are the Champions” played over the loudspeakers.

“Oh man,” said Jake. “How awesome would that be?”

Seeing these Orioles reach the World Series at the beginning of their careers would be magical. But until then, Jake and I will be texting every game, celebrating the highs, ruing the lows, and wishing that the Orioles would send McKenna back to the minors.

“Bro how awesome was it yesterday!!!” he texted the next day. “So fun hanging with u guys. And the win was 😘”

A final side note: In the ‘70s, when the Orioles would win, their radio play-by-play guy would give his celebratory catchphrase, “Ain’t the beer cold.” The Orioles went on to sweep the Mets and have the best record in the American League. If the season ended today, they would get a first-round bye in the playoffs and have home-field advantage. (Also, the Yankees are in last place.) But I don’t want this season to be over. There are 60 games left, which means 60 more nights to live and die by these goofy kids. And they way they’re playing, the beer is going to be very cold for a while.

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!

Very good.

See you in October