Will the end of social media be the return to social networking?

Another wedding, another lesson.

Welcome to all our new subscribers! Welcome to the party. You came for the economic gloom, stay for the optimism, sort of, about social media, maybe! This week, we’ve got essays from Frank Spring with an unusual but smart theory why the GOP missed the midterms and from debut writer Griffin Burrough with what you need to know about the World Cup.

But first, at a lesbian wedding this weekend I was reminded of what a friend of mine once said about making romantic connections on Twitter. Sure, Twitter wasn’t designed as a dating app, but she was using it to arrange dates on her business travels. “Sooner or later,” she texted, “every social media platform becomes a dating site.”

At the wedding, one bride said that she had used her regular opening line on the dating app Hinge: “Where was that picture taken?”

“It took her two months to reply,” said the one bride of the other. “I was hooked.”

It shouldn’t matter that it was a lesbian wedding, except that I had been married twice by the time these women were allowed to. And it was longer still before Silicon Valley gave LGBTQ+ folks ways to make safe connections in digital versions of the safe spaces that gay bars used to provide. You can’t bring a gun into Grindr.

We live in a world where one woman wanting to publicly declare her love for another exposes her to the possibility of violence. Being able to make a safe digital connection is progress I could not have imagined when my closeted uncle died of AIDS in the ‘80s. To me, it was significant that I was at a lesbian wedding in a state so conservative that holding hands in school is illegal, and it was facilitated in part by a digitized social structure that’s now so ordinary we don’t think it noteworthy.

Twitter’s impending collapse feels like a bigger deal than delicious comeuppance for the world’s richest man. Mark Zuckerberg is throwing good billions after bad in his losing bet on the metaverse. And as my buddy Frank pointed out earlier, the anti-social online dystopia that Republicans campaigned on didn’t correspond to actual reality.

It feels like the age of social media — in which we prioritized and weaponized our judgments of others — is ending.

Ian Bogost published a pre-eulogy for social media in a brilliant piece in The Atlantic, in which he charted the course social networking took into social media. Remember the old days when we used Facebook to reconnect to friends from high school? And then, when the homepages turned into news feeds, how we muted our high school friends who’d turned into Trumpy anti-vaxxer Russian apologists? All of a sudden, fairly benign connection machines had turned into…

…a global broadcast network where anyone can say anything to anyone else as often as possible, and where such people have come to think they deserve such a capacity, or even that withholding it amounts to censorship or suppression—that’s just a terrible idea from the outset. And it’s a terrible idea that is entirely and completely bound up with the concept of social media itself: systems erected and used exclusively to deliver an endless stream of content. … Social media showed that everyone has the potential to reach a massive audience at low cost and high gain—and that potential gave many people the impression that they deserve such an audience.

But as social media grew, the billionaires got greedy and shifted to an engagement model. They adjusted the algorithms to hook us with fear and outrage, which is easier with conservative minds than liberal ones, and the experience of spending time on a social media site felt worse. Russian disinformation bots turned our buddy from Cub Scouts into a sneering troll. The guy you dated in the ‘90s became an insistent Reply Guy. The algorithm came with a cost that we paid in damaged relationships, but it kept people hooked, and the social media giants got fat as brands moved their advertising dollars onto Facebook, Instagram, et al.

Meanwhile, as Scott Galloway recently pointed out, Apple changed the rules.

A year ago, Apple’s iOS upgrade forced apps, including Facebook and Instagram, to ask users for permission to track their data. Meta relies on that data to serve personalized ads that garner greater clicks and sales. So if users opt out, the ads become less effective, and Meta, dramatically less valuable.

But few predicted the change would hurt Meta this much. Turns out when Apple’s privacy prompt pops up, only 16% of users agree to being tracked. And if data is the new oil, ad platforms are losing 84% of their Brent Crude. Apple has gone Putin on Meta’s Germany by cutting supply — though this decision was positioned more virtuously, in the name of privacy, vs. war.

We’ve seen a lot of news that Twitter is losing advertisers faster than its most-active users, but the migration of advertising dollars away from social media has been obvious for a while. As a business model, platforming neo-Nazis isn’t what it used to be. Elon Musk thought Twitter had a free speech problem, but its challenges were much bigger. The business model of the entire industry had changed, and he missed it, bless his heart.

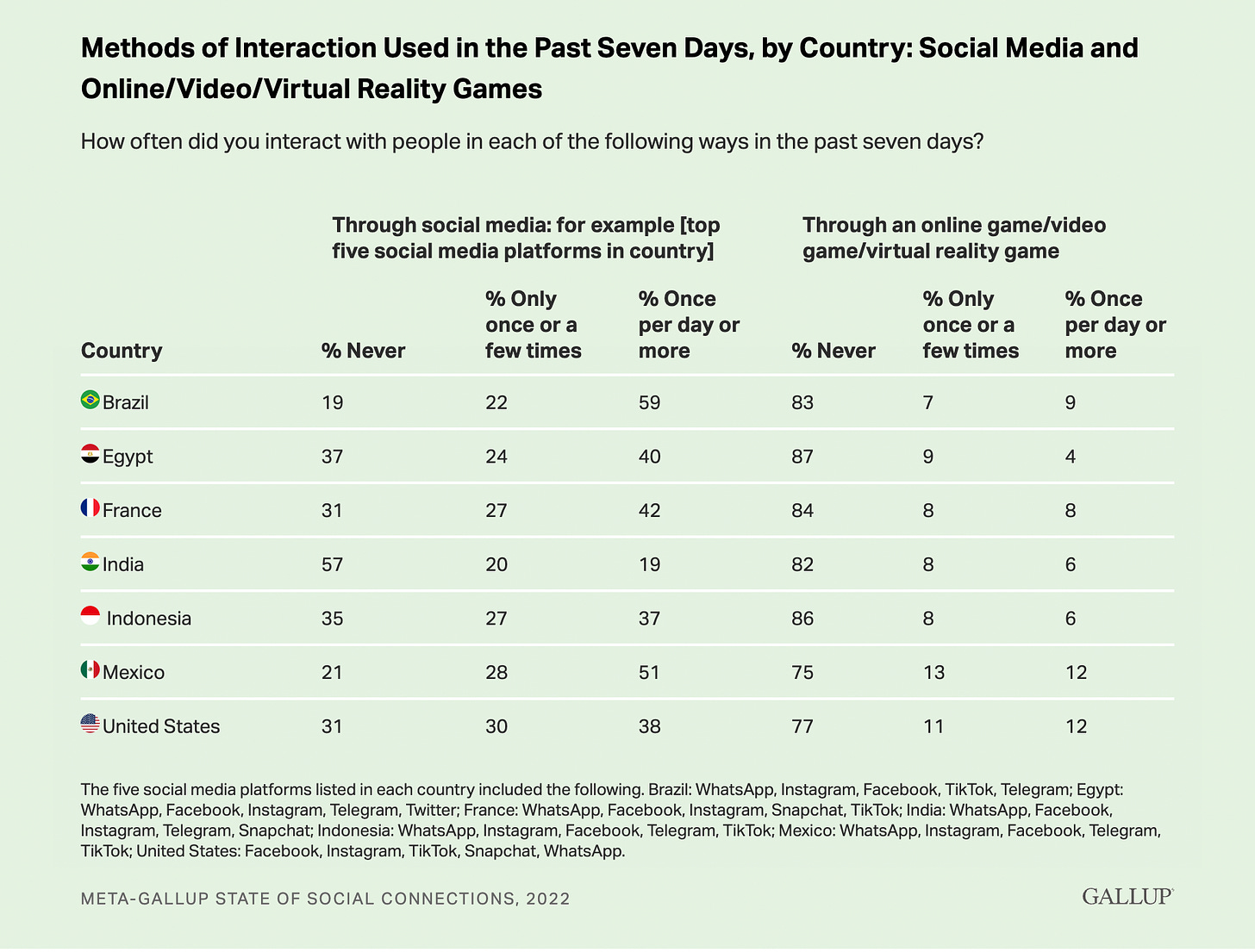

And yet. For all the damage that social media has done, the connections remain. According to a recent Gallup poll, more than two-thirds of Americans communicate with people via social media every week. Maybe they are having side conversations in the comments to a photograph posted while on vacation. Maybe you’re sliding into your dad’s DMs. (And by the way, if you’ve taught your dad to direct message, kudos.) But on a platform re-engineered to make teenage girls feel bad about their bodies, I exchange messages with S, jokes with my buddy Tom, and attaboys with professional contacts. Life finds a way even in a cesspool.

As bad as social media has become, social networking remains. We are less alone because of it, especially those of us out of the regular physical milieu or regular social interaction because we’re disabled, widowed, or working for Elon Musk and working such long hours that you’re sleeping at work.

And for that matter, we’re connected here. I have in my mind some of you who read this — those of you whom I know IRL who tell me you read this, god bless you — but there are others. By reading this newsletter, you’re creating a connection when you open the email delivering the latest edition, reading it, and then sharing it. I might never have met you, but we’ve made a connection on Substack without the insidious hand of any algorithm. And I write this every week in part because you’re expecting it. I don’t want to break the connection.

There is no better evidence that social networking will survive social media than the wedding we went to. They sought each other out first on a dating app, Hinge. Love finds a way, I guess.

I’m told dating apps have no social media functionality. On Venmo, the payment app, there’s a news feed showing what everyone is paying each other for. A friend tells me there is no equivalent on Grindr. You don’t know who hooked up or — oh god, can you imagine? — how each party rated the encounter. When Ted Lasso spent the evening with Sassy Smurf, he reassured her that he had a good time by saying, “Five stars, certified fresh.” It was cute when he appropriated the language of social media for their assignation, but no thank you, please no, I ask so little of the world. Please can we avoid carrying around online ratings as lovers in real life?

Dating apps have stood watch against the onslaught of social media, protecting their networking function against broadcasting our business on main. Here, they have said, and no further. Sexual activity has always stood at the vanguard of technological advance. Perhaps in resisting social media, dating sites, the most private of all social networking sites, show us what is enduring in all of this.

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

Bonus Coverage

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback now!