We're already in the metaverse

We already live online; a metaverse would just invent new real estate

Welcome to The Experiment, where it looks like Ann Kitchen isn’t going to send me a list of specific corrections she wants in last week’s newsletter after all. A day after it went out, she emailed, inviting me to her office to hear what she really thinks about affordable housing. I suppose she wanted me to judge her position on what she said in private rather than on what she said in public, or for that matter what she did. I offered to consider any corrections if I got the facts wrong; she promised to email a list the next day. Since then, crickets.

This week we’ve got Jill Charlotte Stanford (no relation) with a remembrance of my late uncle that hit home especially for me. And I have some thoughts on the metaverse that are, in fact, meta.

As always, we recommend things to do (think like an engineer when it comes to COVID), read (Michael Gerson on “terminal bothsiderism”), watch (The Eternals - “a Marvel movie for everyone who complains about Marvel movies”), and listen to (Spoon’s new “The Hardest Cut” has a Texas roadhouse vibe).

But first, can we all stop with the jokes about Meta?

One of the most-demonstrably evil companies in human history launches a new product that would commodify a new realm of human existence, and all I saw online were jokes about the name: Meta. “Meh-ta, amirite?” was the general vibe. It’s one thing for the news media to revert to theater criticism and for the political chaterati to judge every new presidential campaign by whether we like its logo. FFS, remember the insane hullabaloo about Hillary’s logo? Politico: “Design experts trash Hillary's new logo.” Wired: “Why Everyone Went Nuts Over Hillary Clinton's New Logo.” New York Magazine: “Everything That's Wrong With Hillary's New Logo.” That’s like an obstetrician inveighing against the color of the car the father-to-be drove his pregnant wife to the hospital in. My dude, perhaps we might better focus on the amoral billionaire’s plans to build out humanity’s virtual existence and not whether he picked a bland avatar or could have picked a better name for his new company. Although to be fair, Innovative Online Industries was already taken, albeit by Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One. At least in his despotic YA novel, the heroes didn’t waste time mocking the company’s name.

What strikes me about Meta’s launch is the unoriginality of Mark Zuckerberg’s thinking. Writers have been imagining a virtual world in which our avatars could enter, move around, and conduct business and such. There’s even been a (not very good) Steven Spielberg adaptation of Ready Player One. This is not a fresh take on how technology can expand humanity’s existence and fails to grasp that the metaverse is happening in the reverse. Humans may someday step en masse into computer-generated worlds to live parallel lives. But right now, technology is building out new space in this one. This is the metaverse.

A clock on my telephone woke me this morning with birdsong, except each of these were computer-generated simulations. There was no clock. The telephone is actually a hand-held computer, and the birds did not exist. I weighed myself on a digital scale and entered it into my Noom app on the telephone-that-is-not-a-telephone. I put tiny speakers into my ears and opened another app so a British Buddhist monk could guide me through 10 minutes of gallingly distracted meditation. Then I opened another app to take me through my morning calisthenics; if I don’t do my exercises, I contribute money to a pot, but if I do them, I split the pot with people I’ve never met. Then I do a kettlebell workout and track the time on the clock-that-is-not-a-clock on my phone-that-is-not-a-phone before I enter the time it took me to do my calisthenics and the kettlebell workout on the Noom app, which accordingly boosts the number of calories I’m allowed to eat that day. During breakfast, I read the newspaper that’s not on paper on my not-real phone, use that not-phone to play music and teach me Spanish while I shower and get dressed.

But, yeah, Zuckerberg, tell me again how you’re creating a computer-generated world for humans.

Last year we each spun off 1.7 MB of data every second every time we access lab results, doomscroll, or buy pants. And this is all happening in this world, not some digital parallel realm. I live in this world but go online to move money (a virtual construct of its own) from my digital bank to the landlord’s. That data boosts my credit score, a digital measure of my commercial worthiness, which in turn affords me more opportunities to buy a different home in this world. To paraphrase the kid from 2014 coming down from the dental drugs, “Is this real life?”

We invented the terms IRL and online because, as natives of the organic world, we wanted to think there was another world on the other side of the keyboard. This served both to protect our sense of our world as being real and the digital world being fake as well as to give rise to the fantasy that we’ve created a new world to discover, like Oz, which WOULD HAVE BEEN SUCH A BETTER NAME THAN META. I mean, come on! We created the ideas of the Internet and the Information Superhighway because it was easier to think of the digital world as a separate one when all the machines existed in this one.

What’s really happening, as my friend Barbary explained to me in 2019, is that the data we spin off is creating our digital dopplegänger. Yes, Digital Jason (I’ll pick a better name, I promise) can go into Meta and buy a billboard or some digital pants or some damn thing-that-is-not-a-thing, but what’s happening in this world is that the idea of each one of us is expanding. There are two of us, the physical and the digital you, in this world. Barbary put it this way, when you pick up your phone, you’re holding hands with your digital self. And that thing you think of as the Internet? That’s just data, and data, like love, is all around you.

The rainbow is an illusion, and there’s no place like home if you’re looking to expand humanity’s reach. When I worked in corporate PR, I talked to technologists who were using virtual reality to allow surgeons to operate on patients on the other side of the planet. They imagined oilfield workers making dangerous underwater repairs from the safety of corporate headquarters. All that is happening in this world.

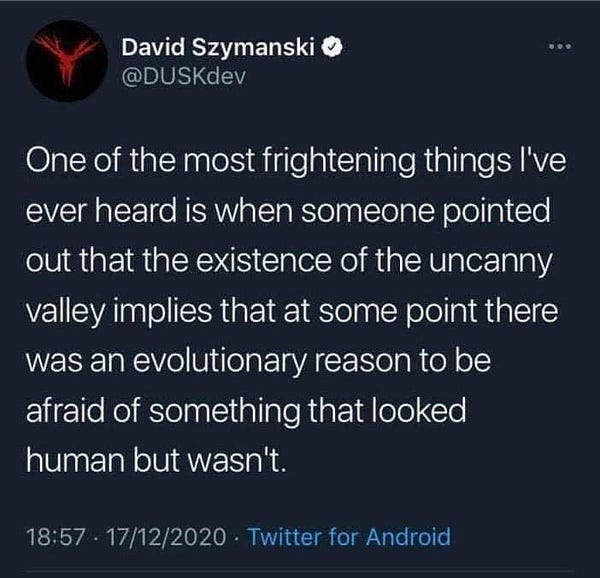

There’s another reason we have to mentally separate this existence from the metaverse: fear of human replication by machines. In the ‘70s, Tokyo Institute of Technology professor Masahiro Mori observed that we like robots to look more like humans up to a point when they have an uncanny resemblance to actual humans, much like the way most bureaucratic verbiage has an uncanny resemblance to actual English. At that point, human support dips dramatically, hence the Uncanny Valley. And as weird as Zuckerberg looks in real life, his avatar bears an uncanny resemblance. This is why we embrace Lego Batman but are creeped out by Tom Hanks in The Polar Express.

A text thread conversation about my wife’s tweet about the Uncanny Valley prompted my friend M, who is not James Bonds’ boss but damn well should be, to mention a book she’d read, Wasteland: The Great War and The Origins of Modern Horror. That book’s thesis is that World War I, which “placed human beings in proximity to millions of corpses,” gave rise to the horror genré. “There are a few chapters on the ‘death doll,’” wrote M, “and why wax work creatures and dolls are so frightening, and it delves into the concept of ‘the uncanny’ and what that triggers in us.” Freud apparently proposed that looking at lifelike-but-not-alive things triggers our repulsion of corpses and “reminds us of our own mortality, and therefore sparks our aversion to it,” as she put it.

The Uncanny Valley might explain why the Matrix was not a rom-com; we’re not so much afraid of technology replacing humans as we are reminded that we’re all meat sacks with expiration dates stamped in ink. That’s not the only reason we imagine a digital world separate from this one. Just because we’re losing our religion doesn’t mean we don’t want to get into heaven even if we have to create it ourselves.

But in the immortal words of Belinda Carlisle, “In this world, we're just beginnin'/To understand the miracle of livin.'” The metaverse is not a separate realm in which technology expands human existence beyond corporal limitations. That world is getting built out all around us. And the digital dystopia we all feared could turn out to be just a better version of the planet that already gave us the apple trees, the Go-Go’s, and pants. We can make heaven a place on earth, or at least use data-driven technologies to expand the possibilities of what it means to be human. Ooh, baby, do you know what that’s worth?

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. He works at the Austin Independent School District as Chief of Communications and Community Engagement, though he would want to point out that these are his personal opinions and his alone, but you already knew that. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

Más

How we’re getting through this

Thinking like an engineer

Cheering the sixth paragraph

Identifying astroturf parent groups

Forgetting the Alamo on the Texish podcast

Forgetting the Alamo on NBC’s Hidden Histories

What I’m reading

Michael Gerson: “Ideologues exist on the left and the right. Only one side threatens the country.” - George W. Bush’s speechwriter gets it.

If the American experiment dies, the cause will be terminal bothsidesism.

Ryan Holiday: “This Was The (Craziest) But Best Decision We Ever Made” - Smart piece about the virtues of brick and mortar in an increasingly digital world.

The irony is not lost on me that the attraction of a physical space is the ability to take a picture that you can share on social media. But it's also a focusing device for me. The Painted Porch can succeed not despite its having a physical storefront, but because of it. If all people cared about was price, they'd buy online. If they want to do something cool on a weekend, they come by.

Maggie Smith: “Rachel Held Evans died at 37, but a beautiful new book captures her brave outlook” - Maggie Smith wrote the hell out of this review.

Dear Reader, please let me begin with a confession: Rachel Held Evans’s “Wholehearted Faith” was written for me. Or, that’s what I thought to myself while reading it.

What I’m watching

Nothing good, that’s what. Second week in a row that our algorithmic overlords have delivered unto me such crap. But Glen Weldon’s review of The Eternals (“A Marvel movie for everyone who complains about Marvel movies”) makes me excited to see it. This trailer first makes me question this inclination until the joke about the table (watch it till the end). Chloé Zhao, who won the Oscar for directing Nomanland, takes the lead on this Marvel movie, the latest in a trend of indie auteurs directing comic book movies that Ann Hornaday calls “sobering.”

What I’m listening to

People, this is not a drill: Spoon has new music out. “The Hardest Cut” is the first single from their next album, Lucifer on the Sofa, which is due out in February. This new Spoon song sounds like a roadhouse band covering Spoon. The slappy slack in the rhythm guitar is a new addition to their arsenal.

My friend W mentioned that “The Hardest Cut” reminds him of what Spoon sounded like before they became indie darlings. I had never heard this song from 2000.

“Bubblegum” is a dreamy, Gen Z, introverted version of Sinatra’s “It Was a Very Good Year.” Quinn Christopherson is an Ahtna Athabaskan and Iñupiaq songwriter from Alaska best known for winning NPR’s Tiny Desk Contest.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds and have kept it off for more than a year. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House.