The Nones

Why are Americans losing their religion?

Welcome to The Experiment, where we can’t shut up or dribble. I mean, you saw it too, right? This week there’s a bit of a theme. I’ve got a theory about why we’re losing trust in institutions, Jessie Daniels tells us that there’s always been racial politics in Atlanta baseball, and Tom Ramsey finds a great way to celebrate Confederate Heritage Month.

But first, if the institutions held, why are we losing trust in them?

A funny thing happened on the way to the end of the world as we know it. Trend lines that had long tracked strange migrations intersected and showed us all in the wrong place, or maybe we haven’t changed but all the places did. In 2020, the “trust bubble burst,” found the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer, leaving us with little faith in institutions, which makes me wonder why we think we should have faith in institutions at all.

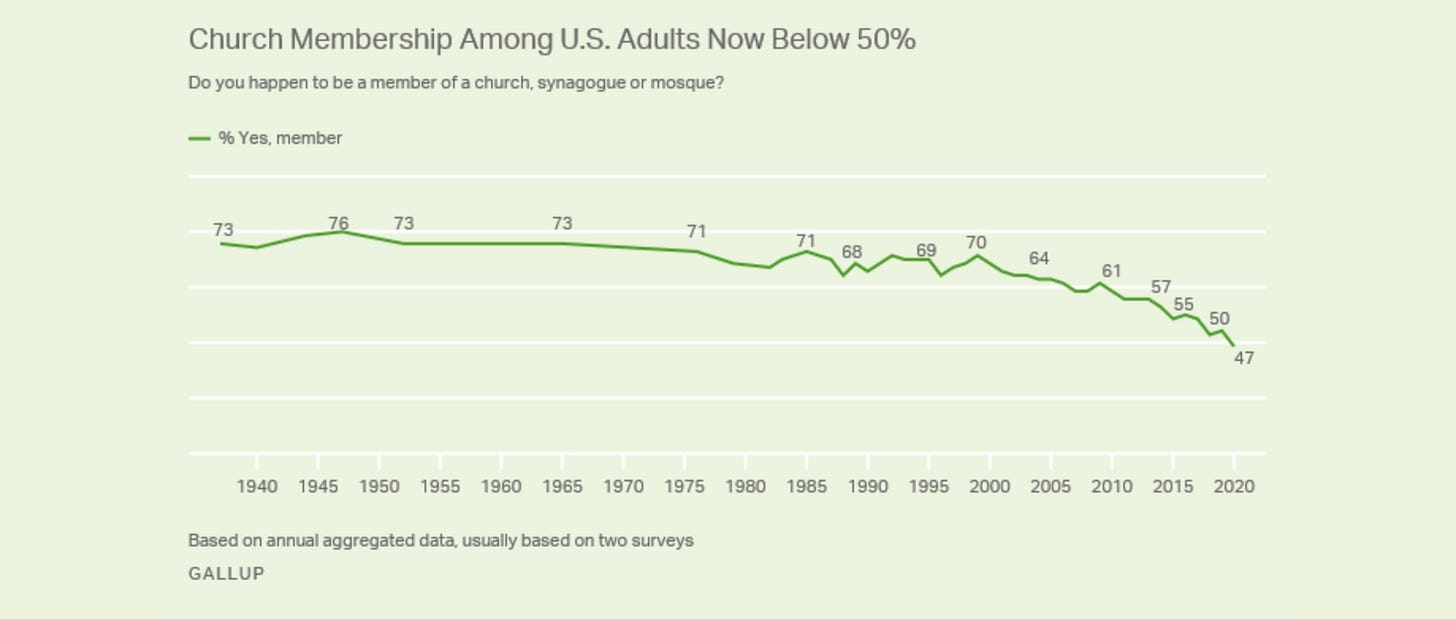

Americans, or at least most of them, used to have faith in houses of worship. When Gallup first asked Americans in the 1930s if they belonged to a church, synagogue, or mosque, 73% said yes, and the answers stayed up there in the '70s until the ‘90s, when, some speculate, the internet led to the creation of online communities that replaced church with virtual congregations. Fewer and fewer Americans chose to belong to a church, and last month, for the first time in American history, a majority told Gallup that they did not belong.

But the Nones, as the new majority came to be called, did believe. Two-thirds of the Nones retained their faith, just not their religion. So while that Facebook group probably fostered some sort of fellowship, that wasn’t what was driving these godly leavers out the church door.

Religion in America, particularly the evangelical varietal, is increasingly defined not by the teachings of Jesus but their the political beliefs of their adherents, if not the political teachings of their preachers. An overwhelming majority of white evangelicals hold religious beliefs about politics, including the belief in things unseen, such as Donald Trump’s victory over Joe Biden.

Many white evangelicals (not all surely, but enough to make it a substantial and well-defined voting bloc) also see Trump as a messiah. In 2019, former Energy Secretary Rick Perry told a story on Fox about a conversation he had with Trump in which he told the President about the bible’s imperfect people.

“And I shared with him, I said, ‘Mr. President, I know there are people that say, oh, you were the chosen one,’ said Perry. “And I said, ‘You were.”

Whatever else you can say about thinking Trump is a messiah to deliver Republicans from secular pluralism, at least it’s an ethos, and it sure as hell isn’t a religious dogma. It’s a belief that the United States should be based on and run according to Christian beliefs. That’s Christian nationalism, a political philosophy.

Why are Americans losing their religion? Churches are acting like political organizations, strange bedfellows and all.

***

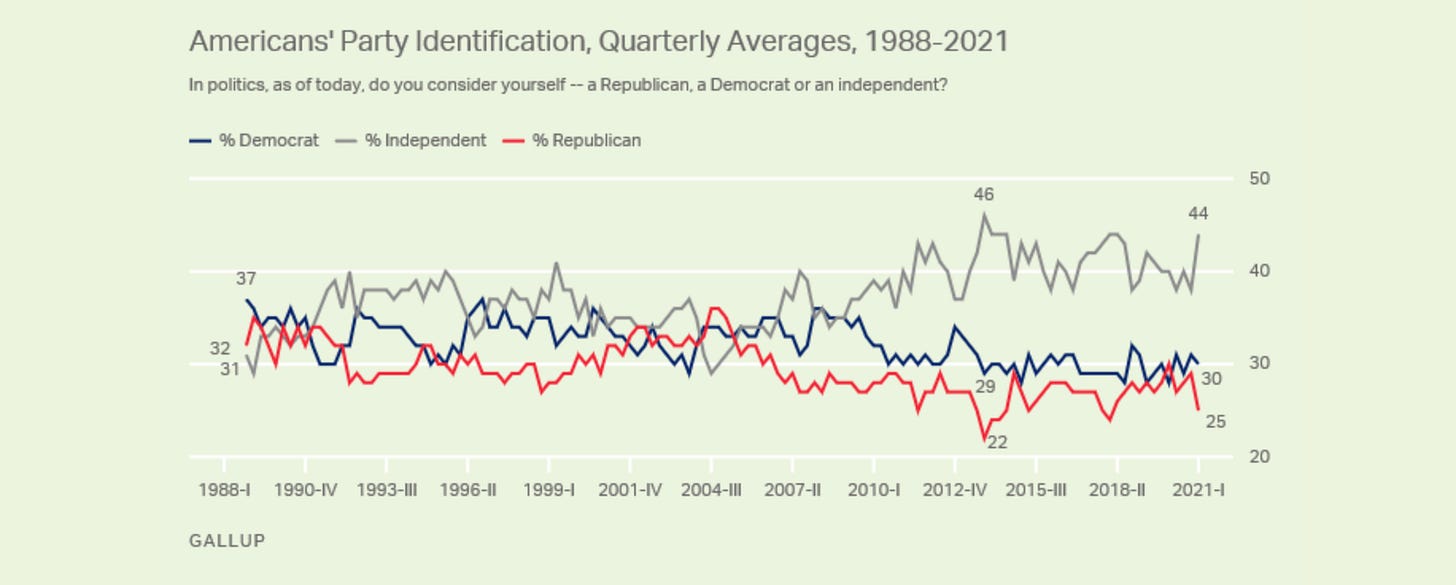

Meanwhile, that same month, Gallup found that our political parties were losing members at the same time. American politics is too often portrayed as a binary choice, but increasingly Americans are opting out of the religious war between Democrats and Republicans.

Though a recent Gallup poll showed Democrats enjoying their biggest advantage over Republicans since 2012, both parties were getting swamped by the political Nones, independent voters. Yes, I know, I know. Independent voters do not vote like independents, just as most of the unchurched still believe in a god. But like those who have lost their religion, the independent voters no longer feel like they have a home in which each party enforces orthodoxy on its members.

Our democracy’s religious roots were so strong they had to build a wall between church and state. And America certainly has original sin even worse, arguably, than what got Adam and Eve kicked out of the Garden of Eden. But strange bedfellows used to be the stuff of politics. Back when most Americans belonged to churches, the Democratic Party was a coalition of working-class Southern white people and Black people.

Now, politics—and by this I include movement activism along with partisan politics—acts more like religion, with values and orthodoxy, than religion does. To some, one man’s angry denunciation of sexist or racist hate speech is one person’s Spanish inquisition and another’s militant religiosity, a spirited and spiritual defense of the lamb against the lion. And instead of from the pulpit, the next-gen leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement came from activism. There is no Gen Z Reverend King because BLM is not, at its core, a religious movement but a political one that’s acting like a religious movement.

And the debates—not the performative podium shows we see every four years—have taken on a life-or-death tone. We contemplate the end of the world with every vote, and compromise, long the grease of good government, is now a moral failing.

“Political debates over what America is supposed to mean have taken on the character of theological disputations. This is what religion without religion looks like,” wrote Shadi Hamid in his Atlantic piece, “How Politics Replaced Religion in America.”

I’ve written before that we’re living through a Cold Civil War, and as it turns out most Americans agree, but I don’t think I’m quite right about that. Politics is not just religion without transcendence but holy war by other means.

***

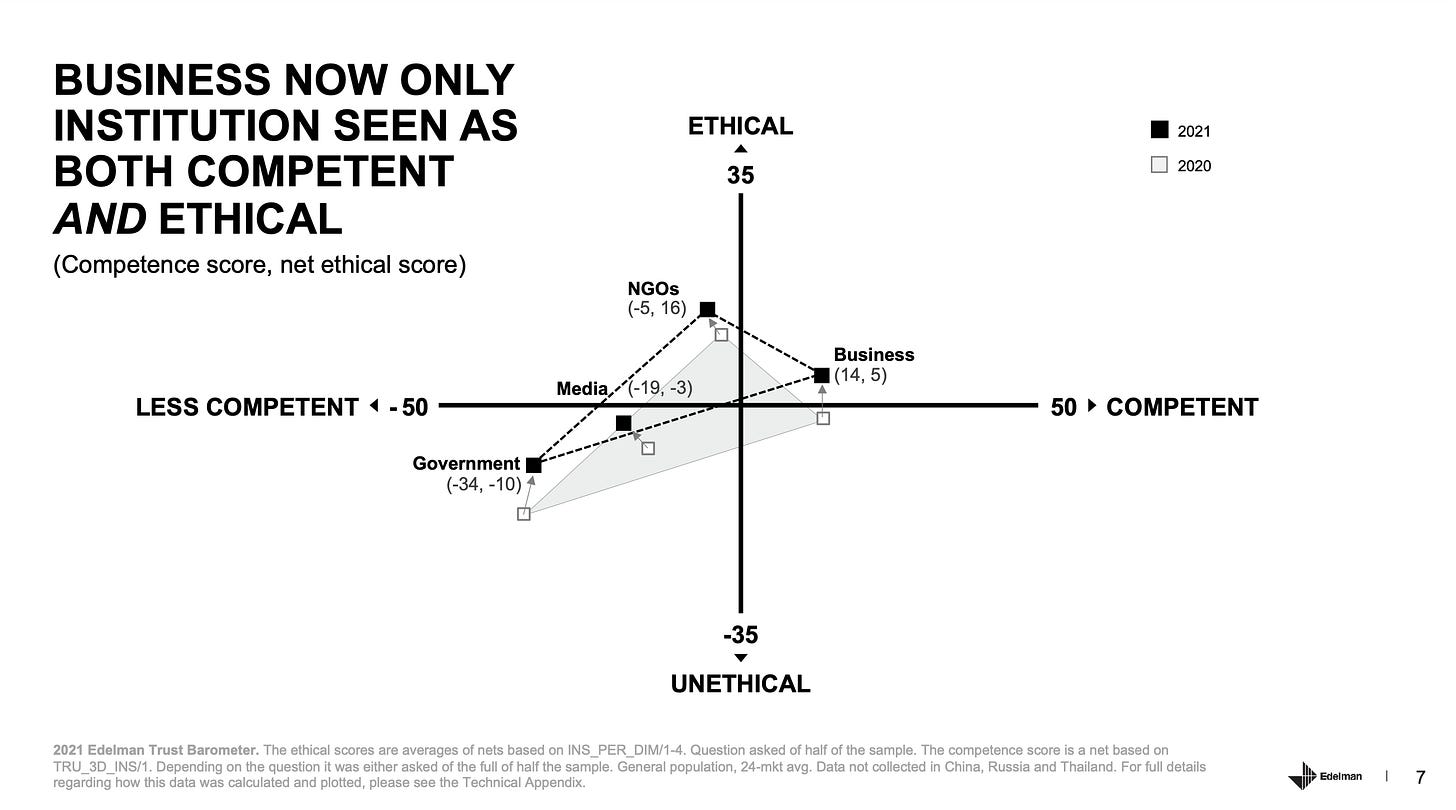

So where do Americans go for their religion now? To work. According to the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer, business is the last trusted institution in the world, trusted more than government in 18 of 27 surveyed countries, including this one.

Increasingly, we’re expecting our workplaces to take moral stands, reflect our values, and speak out against injustice—that is, to speak truth to power. And increasingly, they are. The Business Roundtable, a group of America’s largest corporations, now routinely speaks out against politicians for voter suppression, inciting insurrections, and other subjects that used to be literally none of their business.

Why? It’s not just that anyone 40 and below sees where they shop and work to be a moral choice akin to joining a church. It’s that fixing society’s problems has become their job, thanks to Larry Fink, the largest corporate investor in the world. Fink sends a letter every year to CEOs of companies he invests in. In the business world, Fink’s annual letter is a big honking deal, but even by his standards his 2019 letter was big. It rewrote the corporate rulebook.

“The world needs your leadership,” he wrote. “As divisions continue to deepen, companies must demonstrate their commitment to the countries, regions, and communities where they operate, particularly on issues central to the world’s future prosperity. Companies cannot solve every issue of public importance, but there are many – from retirement to infrastructure to preparing workers for the jobs of the future – that cannot be solved without corporate leadership.”

Shareholder capitalism is dead. Now companies incorporate environmental, sustainability, and corporate governance into their business metrics. They judge themselves, that is, by the affect they have on the world, which is why you’re seeing more and more CEOs forcing their companies to take concrete steps on climate change, to stop selling guns, and to spend real money and time to recruit women and communities of color into coding programs. This isn’t performative but a business imperative, and in the era of stakeholder capitalism, CEOs are the new politicians, and the office is the new church.

***

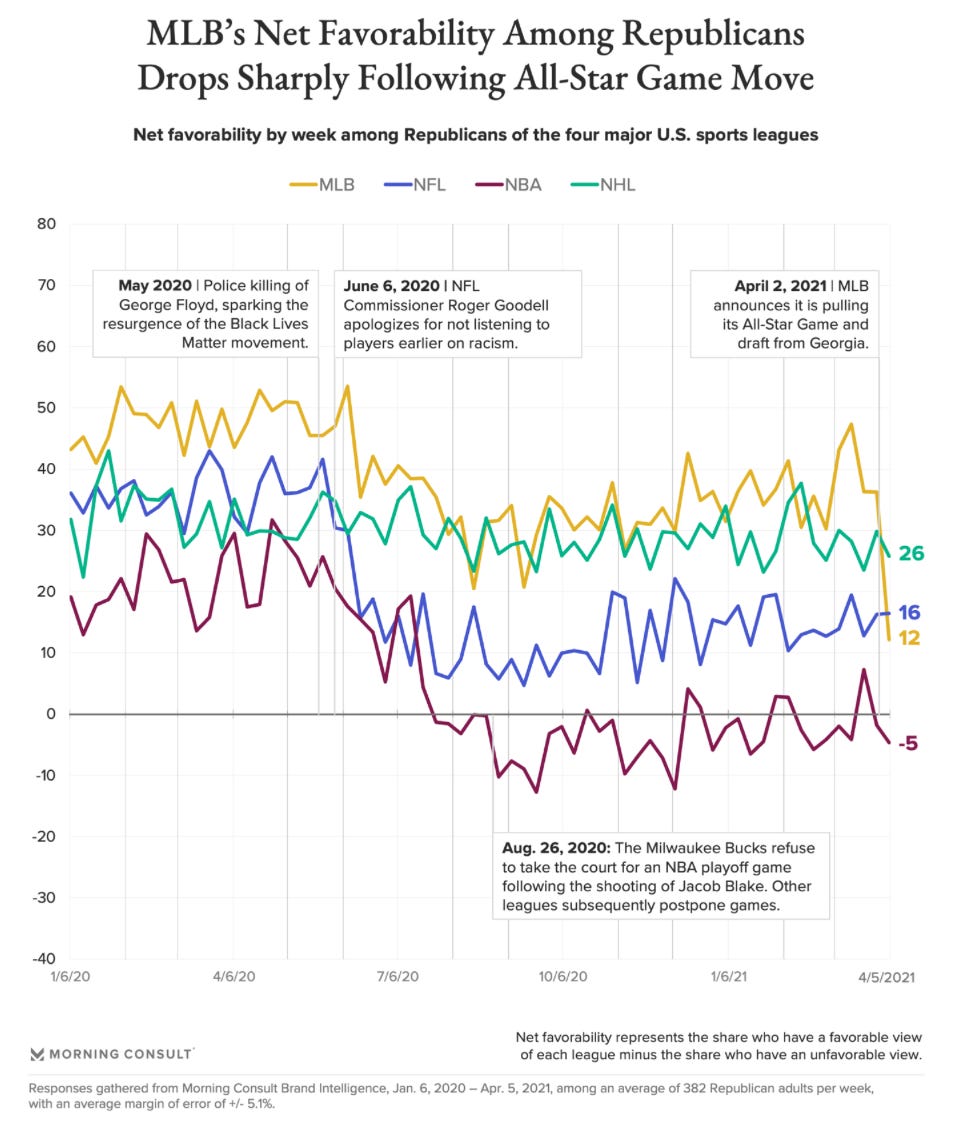

We used to think of sports as religion, but increasingly sports teams are behaving like political organizations, choosing whether to go to the White House or kneel for the anthem, whether to protest police violence or shut up and dribble.

In truth, there has always been politics in sports. Segregating and then integrating major sports was a political act. A political act, Title IX, provided athletic opportunities for women. Kareem Abdul Jabbar never shied away from talking about racism before LeBron James was even born. And Muhammed Ali lived one of America’s biggest political lives, from his embrace of Malcolm X to his refusal to go to Vietnam to his endorsement, much later, of Ronald Reagan.

What’s different now is that Americans perceive sports politically. After Major League Baseball pulled the All-Star Game from Atlanta to protest the voter suppression bill, the league’s net favorability among Republicans dropped 35% to 12%, below the NFL and above the NBA, which for some reason they seem to hate. At least Republicans have golf.

So what’s a None to do, with religion acting like politics, politics acting like religion, business acting like both, and sports, which used to be a religion, is now politics. I say, embrace the one true religion, the only one with a working moral compass and a heart of gold. I speak, of course, of Ted Lasso. Say what you will about Apple TV’s sitcom, at least it’s an ethos that’s guaranteed to return again. New episodes drop in 2022. So we’ve got that to look forward to, which is nice.

The Truist Test

by Jessie Daniels

Major League Baseball moving the All-Star Game is not an example of virtue signaling, writes Jessie Daniels, but the latest point in a long story about politics, business, and race.

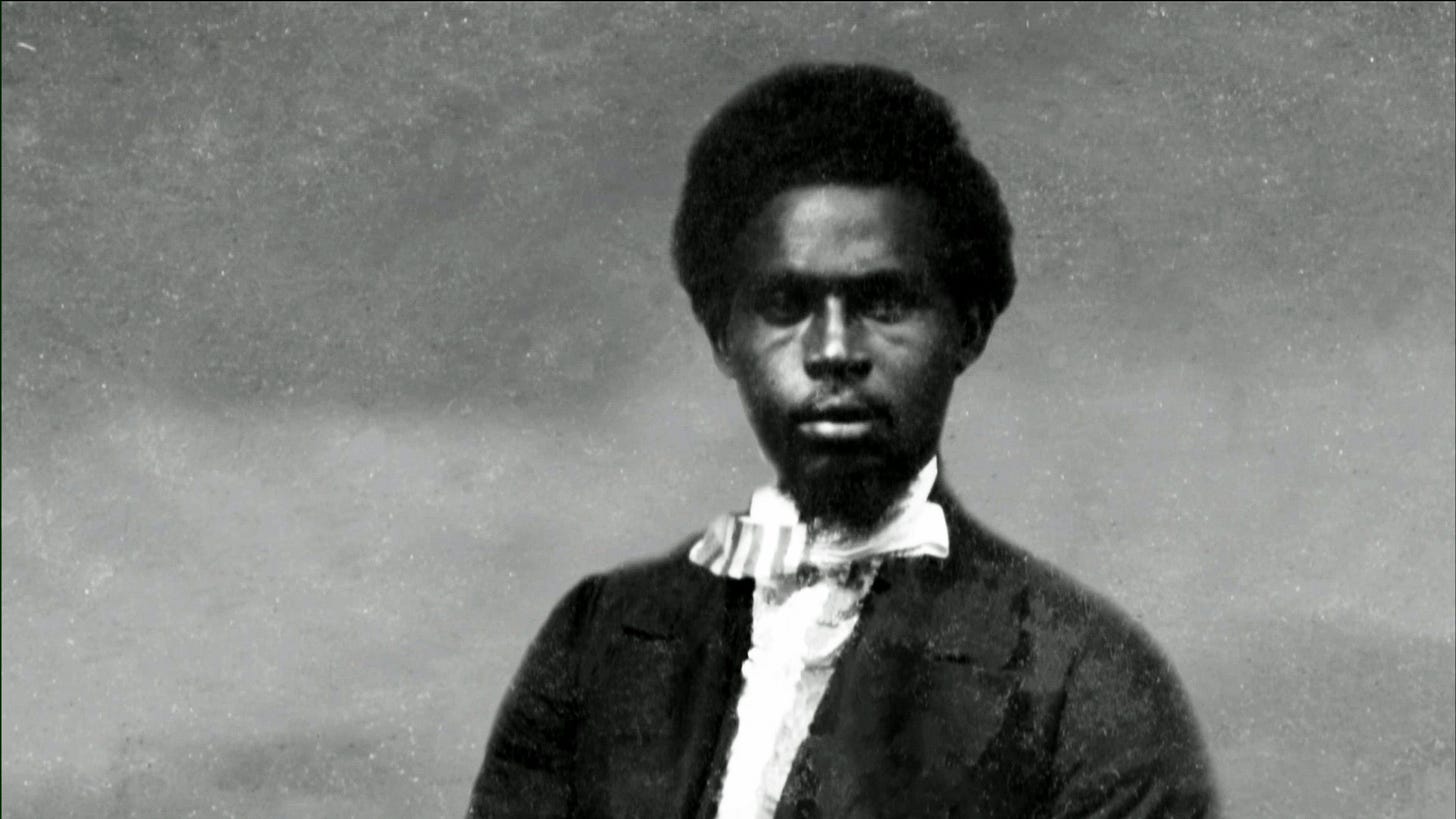

A Son of the South

by Tom Ramsey

What if the Confederacy really did produce heroes… just not the ones that you think. Tom Ramsey, who last month told a strange tale of new love and near death, returns to mark Confederal Heritage Month by remembering a real hero, Robert Smalls.

Who we’ve lost

This 99-year-old

How we’re getting through this

Waiting three seconds

Becoming data-friendly

What I’m reading

Lauren Collins: “The Unlikely Rise of French Tacos” - This is not The New York Times.

Technically, the French tacos is a sandwich: a flour tortilla, slathered with condiments, piled with meat (usually halal) and other things (usually French fries), doused in cheese sauce, folded into a rectangular packet, and then toasted on a grill. “In short, a rather successful marriage between panini, kebab, and burrito,” according to the municipal newsletter of Vaulx-en-Velin, a suburb of Lyon in which the French tacos may or may not have been born.

Brad Esposito: “Maybe the kind of reform that we want comes from creators being like, ‘I’m done'” - A thoughtful discussion on platforms and creators.

I think if we really, truly, with our feeble brains, could understand what is happening when we’re about to hit send on a tweet or post or upload a video or something — I think if we really could understand the power there, we’d all just be like: Man, I’m out.

What I’m watching & listening to…

Will return next week. Honestly, I’ve been too busy to focus.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

If your new year’s resolution was to lose weight, try Noom, and you’ll quickly learn how to change your behavior and relationship with food. This app has changed my life. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works.

Headspace is a meditation app. I’ve used it for a couple years and am absolutely shocked at how much it’s taught me about managing my inner life. Try it free for a couple weeks. Don’t worry if you’ve never done it before. They talk you through it.

I now offer personal career coaching sessions through Need Hop.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had.

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.