There will be feasting and dancing in Washington next year

Which America will we inaugurate in a year?

It’s Saturday morning when I sit down to write this. Three years ago today, Joe Biden was inaugurated in Washington, DC. “This is America’s day,” he began. “This is democracy’s day. A day of history and hope. Of renewal and resolve.” Seven years ago, Donald Trump began his presidency by declaring the dawning of nationalism and isolationism: “From this moment on, it’s going to be America First.”

Which version of America will be celebrated this time next year?

Last week the Republicans began their answer with the Iowa caucuses held during an extreme cold snap. An Arctic blast dumped snow as temperatures dropped below Moscow’s, to use a completely random example. Trump was the heavy favorite, and some worried that complacent caucusers would use the weather as an excuse to stay home.

And at least one saw a conspiracy. “Is the Deep State activating HAARP to disrupt the Iowa Caucus?” insinuated Laura Loomer, a white nationalist who presents herself as an investigative journalist. HAARP is a previously military-funded high-power radio transmitter in Alaska that a university uses to study the weather… and to rig elections, apparently.

“Is the Deep State activating HAARP to disrupt the Iowa Caucus?”

“We all know @NikkiHaley has a lot of friends in the defense industry and Military industrial complex. She's losing in Iowa, and now Iowa is set to get hit with a ONCE IN A DECADE blizzard as Donald Trump is set to dominate the Iowa Caucus,” Loomis posted on the anti-social media platform formerly known as Twitter.

Good luck using facts to get Loomis out of that ditch. My late friend Harold Cook liked to say that you can’t use reason to get someone out of a place they didn’t use reason to get into. That’s always been true, but now it’s made worse by the fact that, for the most part, people—and we’ll get to which people in a minute—only trust themselves to find the truth about new things, like viruses, ballot boxes, and radio transmitters.

If you’re like me, you’re barely holding onto the hope that facts might in fact be stubborn things, that the truth is the tortoise and falsehoods the hair. OK, if a person trusts themselves to do the research, might actual research enlighten them?

That would be putting Descartes in front of the fact that the Enlightenment was a lie, because our brains are so horribly dumb. A recent study asked people to do their own research on fake news and found “consistent evidence that online search[es] to evaluate the truthfulness of false news articles actually increases the probability of believing them.”

The professors placed part of the blame on what are called “data voids” and Google’s paradoxical offering up of unreliable information where credible facts don’t exist to prove a negative. (For example: “Hillary Clinton’s pedophilia ring at Comet Pizza” is going to return the absence of evidence. It does not exist. Instead, Google will offer up a glut of poppycock asserting the opposite.)

But I think a bigger issue is our brains’ vulnerability to language. We’ve talked before about homo sapiens existing several million years before language took up residence in under-used parts of our brains, as well as how this played a role in our winning out over the Neanderthals. Something about our skeleton and situation at the time made humans uniquely susceptible to language.

“Hey, Olaf, look over here!”

I’m not talking about the ability to communicate, though I imagine, “Hey, Olaf, look over here!” was a great diversionary tactic against Neanderthals. I’m talking about language as in cave drawings or a picture of a heart meaning both the organ and love, as in you, right now, connecting the idea of a picture of a red heart to someone you love, or loved. Better to have loved and lost, I suppose, than have rationalized voting for Trump in the first place.

What did we homo sapiens use for the nearly two million years before we downloaded the language upgrades? We had the unconscious, which Cormac McCarthy calls a “machine for operating an animal” but I think of it more as our operating system. Language didn’t replace our unconscious; it sits on top of it, like Microsoft Word on top of… You know what? I have no idea what the operating system on my laptop is because it’s just there.

And your unconscious is suspicious of your chatty newcomer. Words are primitive tools of suspect compatibility to an OS, which continues to run its systems without them. Sometimes, when we close the language app, the unconscious allows us to convey meaning without words, to understand intention with a look, and think of the answer as you’re falling asleep, everything falling into place without reason and logic, just so.

Language didn’t replace our unconscious; it sits on top of it, like Microsoft Word.

Here’s an example: Sometimes in college I would look at math problems and know the answer. Only then would I pick up a pencil and figure out why that was the answer. Your unconscious solves math problems; your conscious brain is its lousy PR flack.

More often, however, your unconscious is a withholding bastard who only trusts you with blunted safety scissors. Want proof? Therapy.

Here’s how therapy works:

Therapist: You seem to be suspicious of people when they say nice things to you. Why is that?

Conscious Jason: I don’t know. Reagan maybe.

Therapist: Dig a little deeper.

Jason: Ronald Reagan?

If your unconscious trusted you with words, this is how therapy would go:

Therapist: You seem to believe people when they say negative things but have trouble taking people at their word when they’re saying positive thing to you. Why is that?

Jason: It would have to be Christmas when I was seven or eight. We were at my mother’s parents how with all the aunts and uncles. I really wanted a Six Million Dollar Man action figure…

Therapist: …a doll…

Jason: …ACTION FIGURE. Anyway, I got it in my stocking on Christmas Day, but on that day I also discovered evidence related to that action figure…

Therapist: You mean a doll meant to make boys feel more powerful and less emotionally vulnerable?

Jason: OK, good point, my bad. Anyway, long story short, the box to the Six Million Dollar Man…

Therapist: …

Jason: …proved that Santa Claus didn’t exist, because in our family what you got in the stocking was from Santa. I confronted my grandmother, and she tried to tell me some story about it dropping from the sleigh, but I told her I knew the truth. That’s when I learned there was a truth behind what people said.”

Therapist: “That’s excellent, Jason. We’ve done some really good work today. Let’s stop there…”

Jason: “This may have been compounded by the fact that the next day Dad had to tell me and my brother than he and Mom were getting a divorce.”

Therapist: [uncapping pen] “Go on.”

Jason: “And what really pissed me off, far more than the divorce ever did, was that my grandparents, aunts, uncles, everyone, knew before I did.”

That latter scenario is something that my unconscious has been trying to get me to understand for decades. I am highly verbal and did pretty well on my English SATs. I am 53 years old but read at a 55-year-old’s level. What I’m saying is I can construct a load-bearing sentence, and still my unconscious didn’t reveal my supervillain origin story to me. It waited until I wouldn’t burn a city down if I discovered someone was keeping a secret about me from me.

Just as homo sapiens were uniquely vulnerable to the language virus 100,000 or so years ago, we are still vulnerable to catchy phrases that embed not just in our brains but also spread in our networks. ALL CAPS FWD> became a cat that can has cheezburger, leading inexorably to “I just met you, and this is crazy/but here’s my number, so call me…”

Divorce, songs, suicide, obesity, and innovative ideas can be contagious.

We have evolved into a monkey-see, monkey-do species vulnerable to viruses in many forms, biological and behavioral. Divorce, songs, suicide, obesity, and innovative ideas can be contagious within our networks, possibly even the mass shootings. Are you connected to thousands of people on social networks? Do you work with large teams of people at work? Congratulations, you’re soaking in it.

“Individuals located centrally within a network will be at both an increased risk for the acquisition of a pathogen,” [Harvard Medical School professor Nicholas] Christakis says tells Fast Company, “and an increased risk for the acquisition of novel information.”

Of course, being aware of ideas doesn’t necessarily mean anything–it’s what you do with it. “While your exposure to new ideas or to new information is an attribute of where you are in the network, your tendency to adopt a new thing is an attribute of you,” Christakis says. “It’s a similar case with germs: being at the center increases your risk of exposure, but whether or not you get infected depends on the resilience of your immune system.”

Groups of people are susceptible to viral ideas, both malicious and benign, just as individuals are, though your mileage may vary. Do you belong to a racially and ethnically diverse political party that would rather argue about the meanings of words than winning an election? That sort of group spreads ideas inefficiently, making it less vulnerable to viral infiltration.

If, on the other hand, we could imagine a largely homogenous political party resistant to change, obsessed with outsiders, and hostile to facts that contradict their beliefs, then we’re talking about a decentralized network of millions of Americans uniquely positioned to believe whatever an enemy might want them to believe about America. Such a hostile foreign power could turn Americans—not all, but a large-enough minority—against American institutions, including the free press, public schools, colleges and universities, and even democracy.

A hostile foreign power could turn Americans against America.

For millions of years, people didn’t have language; and then all people had it. For a long time, the Republican Party existed for a strong national defense, especially when it came to the Soviets. And then Trump, aided by Russia’s “Firehose of Falsehood” disinformation strategy, came along.

Whether Russian interference led to Trump’s win in the 2016 election is an impossible question to answer. Thanks to the Senate Intelligence Committee, it’s established fact that Russia interfered with the election on behalf of the Trump campaign, which did not exactly refuse the help.

Far from a hoax, as the president so often claimed, the report reveals how the Trump campaign willingly engaged with Russian operatives implementing the influence effort. For instance, the report exposes interactions and information exchanged between Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik and then-Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort. According to the report, campaign figures “presented attractive targets for foreign influence, creating notable counterintelligence vulnerabilities.” (Manafort was later convicted of tax and bank fraud.)

#NotAllAmericans. According to a 2023 study published in Nature, “exposure [to Russian disinformation] was concentrated among users who strongly identified as Republicans.” Whether or not the Russian firehose picked an American president is not only unknowable but immaterial. What we’re left with is a country populated with Republicans who are supremely screwed with and reciting Russian talking points.

Now we’re left with an ungovernable country because one half of congress seems primarily if not exclusively focused on destabilizing our democracy. Wee!

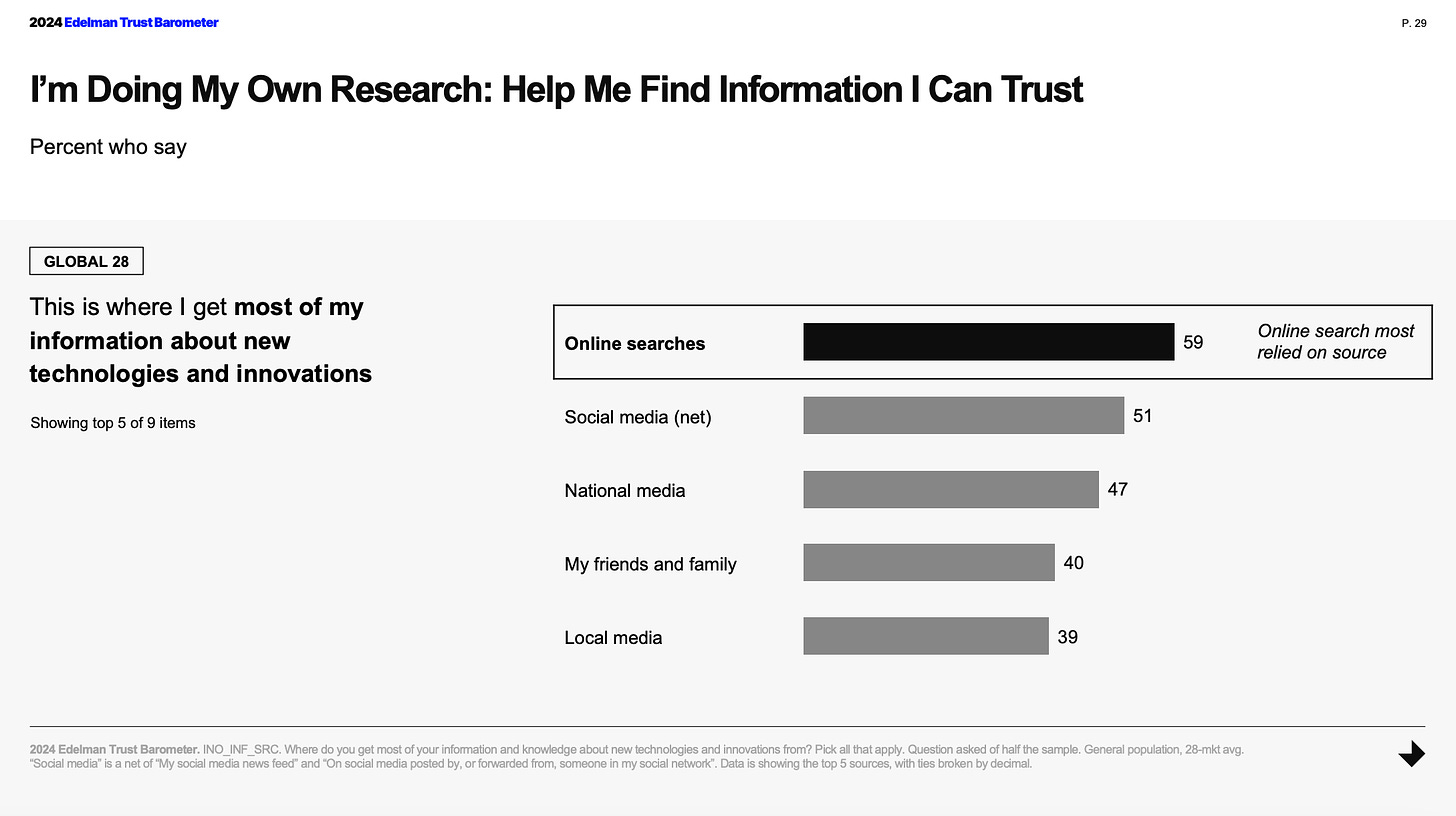

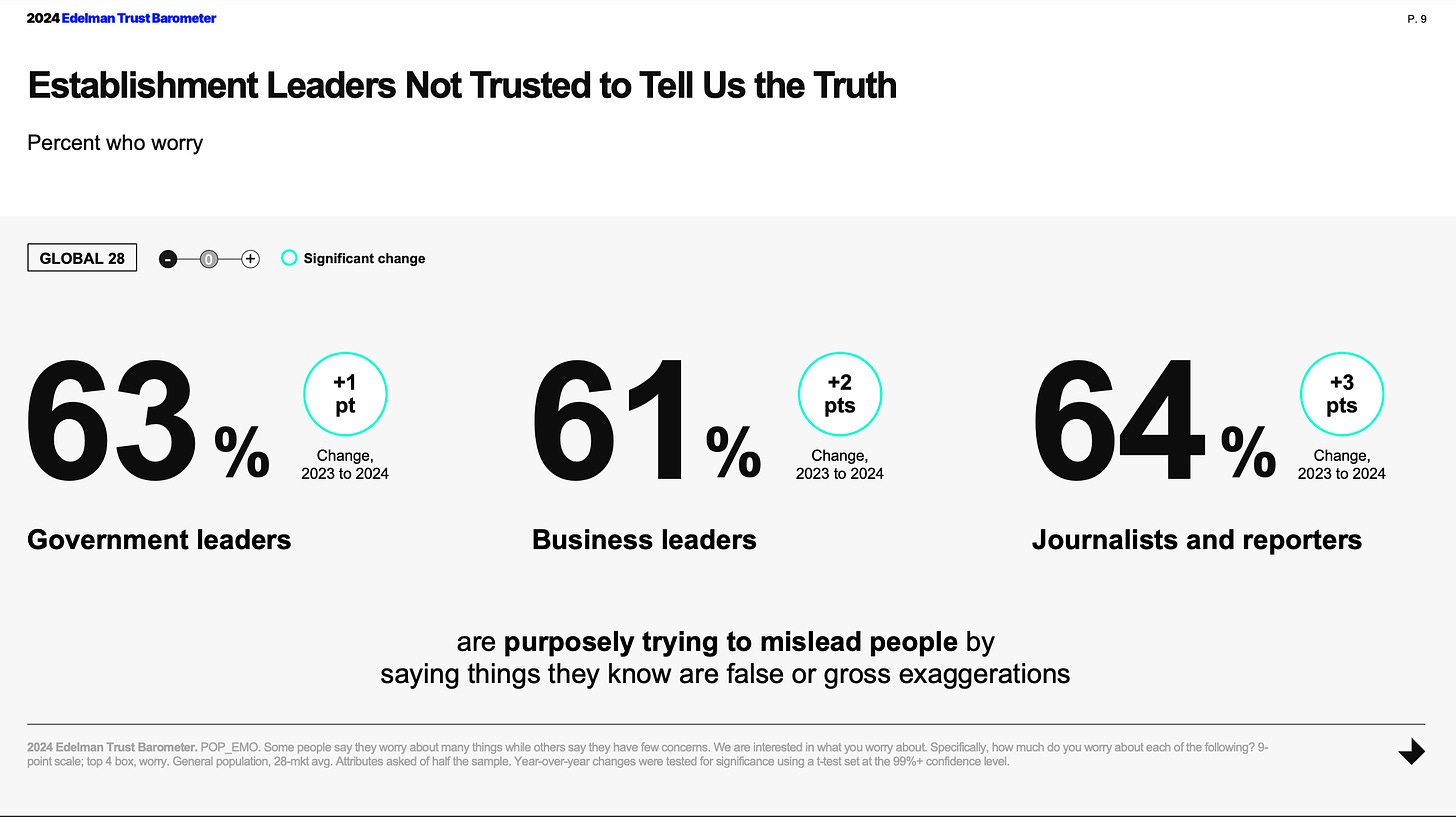

To be fair, a lack of trust in leaders isn’t exclusively Republican or even American. The latest Edelman Trust Barometer found that majorities of people around the world worry that the news media, government, and business is lying to them.

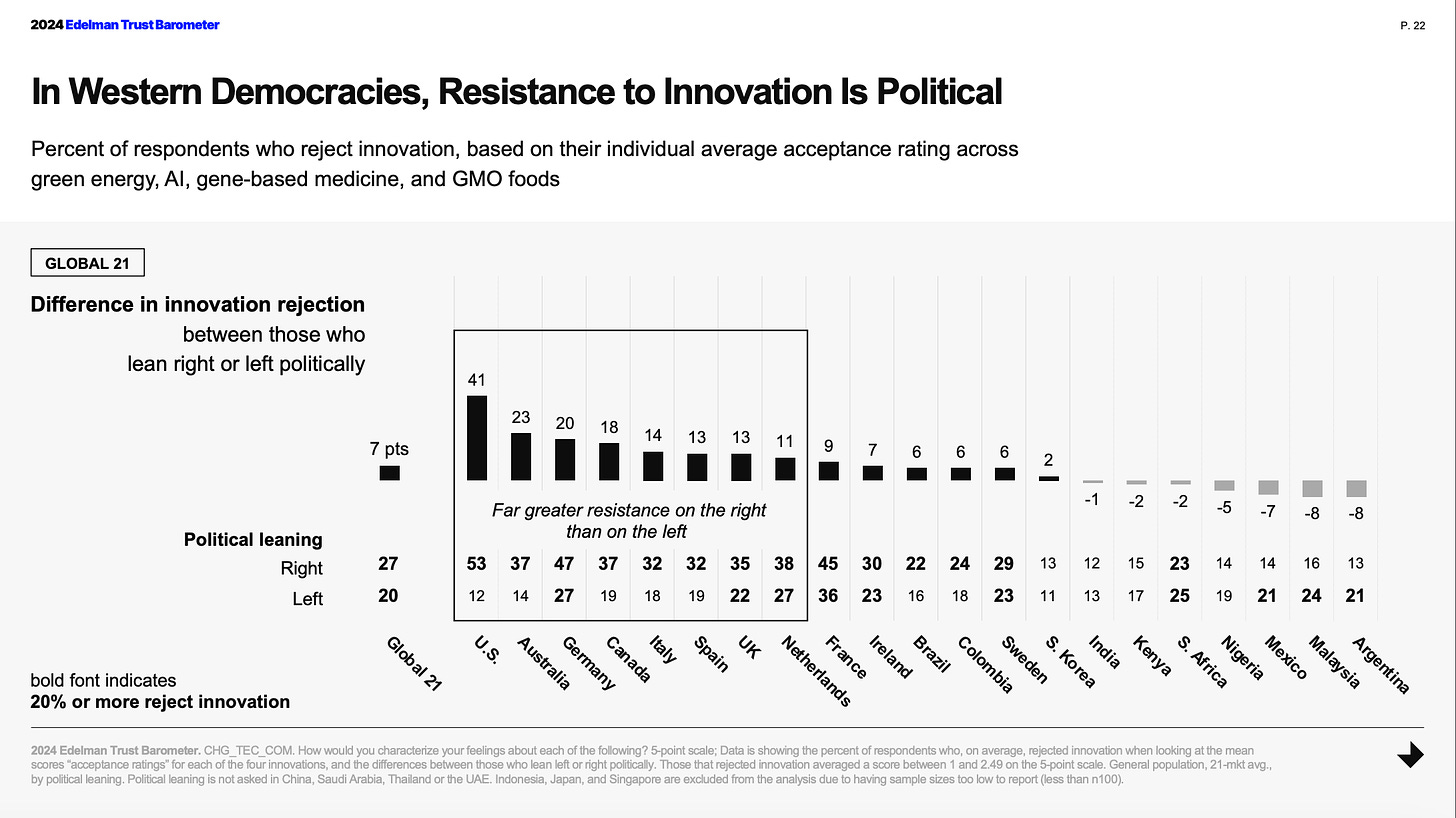

But there is no debate about where that distrust is concentrated among Americans. Republicans are less likely to trust any news media at all than Democrats are to trust conservative outlets, and they really don’t trust social media companies. Also, American conservatives are the most suspicious to technological change and innovation than anyone in the world.

This is bigger than a political problem, or better said this political problem is bigger than one election. This situation in which we can’t agree and are unable to individually discern what is real or collectively repel what is a lie is now among the biggest threats facing the world, according to World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2024.

After the hottest Northern Hemisphere summer in recorded history in 2023,[ii] two-thirds of respondents selected Extreme weather (66%) as the top risk faced in 2024. El Niño, or the warming phase of the alternating El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, is expected to strengthen and persist until May this year.[iii] This could continue to set new records in heat conditions, with extreme heatwaves, drought, wildfires and flooding anticipated.

AI-generated misinformation and disinformation (53%) and Societal and/or political polarization (46%) follow in second and third place.

This is going to be bad for the next two years, says the WEF. And then it’s predicted to get much worse, especially when it comes to extreme weather crises caused by climate change. Remember when we used to fight uselessly about whether climate change was real? Ha, ha! Now we have what The Verge calls a “New Denialism” in which conservative thought leaders such as Jordan Peterson argue that the solutions would come at too great a cost to developing nations, so why bother?

I feel like a fool, chasing the truth like an old man trying to grab a discarded plastic bag that is swirling in the winds in a courtyard. I know it’s useless. Best case scenario, the bag ends up in a landfill, but I’d feel better if things were sorted, facts from lies, park from litter.

“New Denialism”

Meanwhile, most of those Iowans who showed up to caucus for Trump did not believe that Biden won the 2020 election or that Trump had anything to do whatsoever with Jan. 6. And though Trump Hulk-smashed his pliant and cowering opponents, some of his supporters still didn’t trust the final delegate count.

“After it was reported that President Trump won every county in Iowa tonight, Democrat shenanigans ensued and now it’s being reported that Johnson County in Iowa, which is a Biden +40 county, flipped to Nikki Haley by ONE VOTE,” posted Loomer, who was very much back on her bullsh*t if she had even left it at all.

The intervening three years of comparative competence and unabashedly pro-American sentiment from this White House has been a brief escape from an abusive situation. I’m reminded of the protagonist of “This Year,” the hopepunk anthem from The Mountain Goats. A teenager slips out of his broken home to hang out with a girl, and some booze. And as good as it feels, he knows it’s only a reprieve. His stepfather waits at home.

I drove home in the California dusk I could feel the alcohol inside of me hum Pictured the look on my stepfather's face Ready for the bad things to come I downshifted as I pulled into the driveway The motor screaming out stuck in second gear The scene ends badly as you might imagine In a cavalcade of anger and fear There will be feasting and dancing in Jerusalem next year

This week, a friend, E.J., shared the link to a choir singing this song. My unconscious did not bother protecting me, and when the Mountain Goats’ John Darnielle transitions from domestic violence to a vision of hope, my cheeks were wet and my eyes were hot. E.J. says “next year in Jerusalem” isn’t an invitation to a fiesta but an affirmation that we will still be alive then. And we won’t survive by explaining to Russians — sorry, my bad — to Republicans why we are right and how they are very much wrong. That is hopeless.

S asked what I was going to write about this week, and it came out in a mess with a doomed ending. It’s not whether we will lose but that we’ve already lost. “If it’s OK with you, I’m still going to fight like hell,” she said.

“If it’s OK with you, I’m still going to fight like hell.”

Oh, right, the whole hopepunk thing. Or, to paraphrase Channing Tatum in history’s greatest movie, Magic Mike XXL, “It’s not about how we go out there and do it, it’s about getting to go out there and do it together.”

This segment of the American timeline ends as badly as you can imagine in a cavalcade of anger and fear. But this is only a scene. This is not the whole play or even an act, perhaps. There is more story to tell. There will be feasting and dancing in Washington next year.

And I’m going to make it through this year if it kills me.

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Threads at @jasonstanford, or email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

This is the always free, reader-supported weekend edition of The Experiment, your official hopepunk newsletter. If you’d like to support my work, become a paid subscriber or check out the options below. But even if you don’t, this bugga free. Thanks for reading!

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is out in paperback now!