Screens

A screen is both a bridge and a barrier.

Welcome to The Experiment, where imitation is the sincerest form of irritation. The Atlantic has started a podcast with WNYC, which, neat, but they picked a name that is not quite their own: The Experiment. They say their podcast “will give listeners the context they need to understand our country right now,” which we perhaps mistakenly thought was their job all along. Well, we were The Experiment before The Experiment was cool, which it most certainly is not, but we do have merch and they do not, to which I say, “Ha,” adding, also, “ha.” (Also, you can’t copyright titles; I should know.)

This week, Jack Hughes indulges his increasingly worrisome Dan Quayle fixation, arguing that he is tested, rested, and ready in Porqua, CoQau? And Robin Whetstone, our Moscow memoirist, makes her return to The Experiment with a lighthearted tale of human connection in Trigger Warning: Poop.

And as always, we remember who we’ve lost and offer suggestions on what to do (order from Black-owned restaurants), read (Tiffany Yates Martin’s advice on getting unstuck in your writing) watch (Deutschland 83 on Hulu) and listen to (Editrix).

But first, can I tell you one of the dumbest things I ever said?

I was 24, coming off Ann Richards’ failed re-election campaign and starting a new job as an opposition research consultant. This was the old days. We had to save everything on floppy discs and use dial-up modems to email reports at 2,400 bauds per second. Those 200-page reports we wrote? Yeah, they took 45 minutes to email, and if your roommate picked up the extension, you had to wait and start all over again. If someone wanted to reach you when you were on the road, they would call your beeper, which would display their phone number, and if it was important they’d add “911.” To return the call you would pull over and use a pay phone and pay for the call with a phone card that would charge you more than $1 a minute. Everything was new then. There was not an app for that yet. We were still learning the names of things.

It was my first business trip with my boss. He liked for his employees to drive him around, so I had to focus on the rural South Carolina state highway, so maybe I was a little distracted when he was asking about how I was set up as far as computer equipment went.

“Does your laptop have Windows?” he asked.

I hesitated. “Well,” I said, “it has a screen.”

He did not fire me on the spot, but he did regret hiring me. In my defense, my laptop did, in fact, have a screen.

Brains don’t work like we think they should. For example, we existed for millions of years communicating non-verbally before a virus we call language infected humanity. Apparently we had enough unused brain space to accommodate prose, puns, and poetry from William Shakespeare to William Shatner. One moment no human on earth spoke a language. Then, in a relative suddenness, everyone did.

But our factory settings still operate on what psychology professor Albert Mehrabian at the University of California, Los Angeles called the 7-38-55 rule. Only 7% of communication is what words we choose, and that’s dwarfed by the sound of your voice, which makes sense. Imagine someone saying “I love you” like they mean it. Now imagine them saying “I love you” with a resigned admission. Now imagine someone saying “I love you” with hateful sarcasm. I can tell if someone loves me by the way my name sounds in their mouth. We all know this to be true, and we didn’t need words to tell us.

The big daddy of communication, clocking in at 55%, is what we see.

“Eyes always, always, always beat ears when it comes to ingesting information,” wrote Andy Craig and Dave Yewman in their excellent and useful, if not foundational, Weekend Language: Presenting With More Stories and Less PowerPoint.

But what do you do when your eyes aren’t able to work like they’re supposed to? Remember the headaches we’d get in the early days of CGI? The graphics weren’t quite perfect, and the perspectives and angles would be off ever-so-slightly so that our brains would try to turn a 90.0056-degree angle into a perfect right angle. Now multiply that by everything you see on a screen larger than your brain has evolved to handle. The digital Colosseum in Gladiator gave me a migraine.

That’s what’s happening to us now. Our great digital migration is forcing us to communicate through screens, which we tell ourselves should be fine. My laptop has a screen. Right there, I can see my coworker Larry, helluva guy. He’s talking to me, I’m talking to him. We have perfectly normal conversations. The other day we had a drink together. So why are video conversations so exhausting that some companies are putting strict limits on their frequency?

“We can communicate better, and therefore we will actually communicate worse.”

For one, we are prevented from touching. If Larry and I were having a drink in The Before Times, we’d at least shake hands. He might even get a bro hug. And sitting next to him, his body language would be telling me whether he was tense or relaxed. He’d touch my forearm to make a point or, if it were baseball season, pat my back to comfort me. (I’m an Orioles fan. It’s been tough.) I get none of that now.

Instead, when I talk to him I see my face in a monitor. I used to do a lot of television news hits, and often I would be looking into a black lens right above a monitor showing my face. I told myself that being able to gauge what my face was doing would help me perform better, but it really only made me hyperaware that I was performing, and instead of coming across like I was talking with a friend I looked like every other cable-news schmo in a suit arguing talking points. Used to be I could only handle a couple television hits a day. Now, thanks to video conferencing, we’re all doing these several times a day.

Even worse, the technology has a delay of milliseconds. Remember the CGI headaches? Now, instead of imperceptible faulty perspective, our brains are registering slight delays between seeing Larry talk and hearing his words. All that effort feels like work.

As a consequence, we’re not only denied a substantial portion of the evolutionary communication from body language, but we are stuck in performance mode, constantly draining the tank in futile efforts to achieve what video technology seems to promise but actually prevents: actual communication.

All we’re left with is the 7% — our stupid words — which is where things get irrevocably impossible. In What Tech Calls Thinking: An Inquiry into the Intellectual Bedrock of Silicon Valley, Stanford University professor Adrian Daub discusses the paradox of communication.

“We can communicate better, and therefore we will actually communicate worse,” he writes. “Or, put another way, communication was often taken to be solving the problems communication has created in the first place.”

We have the capacity for non-verbal communication, to know by being in the presence of another what that person is feeling and wants to communicate. But we use our stupid words, which in the best of times are only 7% effective. These are not the best of times, though as Daub writes they haven’t been since we started communicating across distances.

“The concept of communication became compelling to philosophers and theorists only once it was both imperative that messages travel with little distortion and clear that they rarely did. The concept designates, as [Professor John Durham] Peter puts it, both a bridge and a barrier.”

A screen is both a bridge and a barrier. Denied the communion of communication, we talk through screens that filter out dopamine and non-verbal cues and connect us just enough to exhaust us to ruin, limiting us to 7% of who we are to each other.

If you were looking for a reason to give yourself a break today, consider this news the mother of all hall passes. You’re doing great, considering most times you’re literally much less human that you were built to be.

The Experiment is free. If you’d like to support our work, you can buy merch for 35% off, toss something into the tip jar, and pre-order my book. Or you can share this, which is the coolest.

Porqua, CoQau?

by Jack Hughes

So Jack Hughes has more thoughts about Dan Quayle, his great white male. We’re not worried about Jack, exactly, but we’re not not worried about him. This week he argues that the Indiana Ideologue is tested, rested, and ready. Even more worrisome is that Jack’s starting to make sense.

Trigger Warning: Poop

by Robin Whetstone

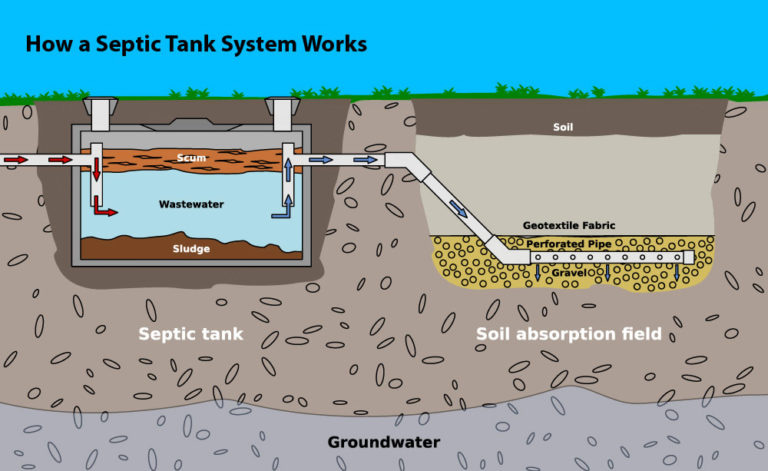

Have you heard the one about what Southerners say instead of “once upon a time?” Instead, they say “y’all ain’t gonna believe this.” Robin Whetstone, who entertained us mightily over months of the pandemic with Red Ticket, her Moscow memoir, is back to tell us what happened when her septic tank backed up, and she doesn’t start it out this way, but y’all ain’t gonna believe this. It’s a happy story.

Who we’ve lost

This photographer

This television writer

This baseball manager

How we’re getting through this

Ordering from Black-owned restaurants

Making one-ingredient banana ice cream

Donating to the Black Voters Matter Fund

Making shrimp scampi with tomatoes & corn

Removing comments sections from newspapers

Making spicy sesame noodles with chicken and peanuts

What I’m reading

Gigi Bradford: “Gigi Bradford on Hailey Leithauser” - Positive reviews are harder to write well, harder still to write like this.

How do you describe something new that transforms what came before? What's the poetic vocabulary for "This book blew my mind?" How did people explain jazz when it first burst on the scene and there was no language for it because its primary referent was itself? Before the terms "Cubism" and "Futurism," how did anyone describe Marcel Duchamp's "Nude Descending a Staircase"? Leithauser's work is this startlingly distinct. You can't describe it; you've got to experience it. As Dickinson wrote, "If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry." This is poetry that rises to and beyond her standard.

Russell Gold: “The Battery Is Ready to Power the World” - Hey look! Good news! I think! (Also: great kicker)

After a decade of rapidly falling costs, the battery has reached a tipping point. No longer just for consumer products, it is poised to transform the way the world uses power.

Michael Hall: “After Eighteen Years Behind Bars for a Crime She Didn’t Commit, Rosa Jimenez Is Finally Free” - Hey, want to read some good news?

Wednesday night, after one of the longest days of her life, Jimenez, staying in a home near downtown Austin, lay in bed staring at the ceiling. “I didn’t want to go to sleep,” she told me. “I didn’t want to go to sleep and wake up in prison again, find out all this was a dream.” Finally, around 3 a.m., she got up. The idea of going outside came to her. In prison, she could only leave her room at certain times. But now she opened the door and walked out onto the porch and into the night. She looked around at the other houses. She stared up at the full moon.

It was chilly, so after a few moments she walked back in, lay down again, and waited patiently for the sun to rise.

Monica Hesse: “No, more sex is not the answer to the country’s problems” - Monica Hesse doesn’t write as much as discover wisdom.

Economic uncertainty, forced home schooling and the daily panic of contracting a deadly illness at the grocery store are not, it turns out, aphrodisiacs.

Kashmir Hill: “A Vast Web of Vengeance” - This is BONKERS.

Outrageous lies destroyed Guy Babcock’s online reputation. When he went hunting for their source, what he discovered was worse than he could have imagined.

Alice Hines: “How Normal People Deployed Facial Recognition on Capitol Hill Protesters” - What if banning technology is a bad idea?

But earlier this month, a new use case for Pimeyes emerged: doxing suspected Capitol Hill rioters.Technologists have also deployed their own facial recognition and detection tools on videos and images of the Capitol Hill riots, but Pimeyes is easier to use.

Tiffany Yates Martin: “Getting Unstuck in Your Writing (Or, POV Is a Bastard)” - Good advice from my favorite writing coach.

I realized I was focusing on the effect of my article, but reminding myself of what drives me shifts focus to my intentions: How could I convey this topic in a way that made it clear and easily understandable? And that puts me right back in touch with my purpose and my rational mind (not the irrational one overcome with doubts): This is information I have and want to share.

What I’m watching

Has anyone ever made a show seemingly created just for you? I spent my junior year of high school in West Germany and studied Russian in college. I still remember the day after the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989 when Professor Spielman held up the front page of the newspaper in Studies of East-West Politics and said, “This is now a history class.” I wanted to be a spy, so I majored in Russian and applied to join naval intelligence in 1992. I was rejected because I’d smoked marijuana nine times. They said due to budget cutbacks the limit was three. When I told my dad he was facing away, painting a wall. The hand holding the brush dropped, and I thought at first that his slumped shoulders indicated disappointment. Then I noticed that he was laughing.

“In the sixties, they would have made you admiral,” he said.

Deutschland 83 starts the hard-luck tale of Martin Rauch, who just wants to be left alone but has a talent for espionage. That’s followed by Deutschland 86, which coincided when I was in West Germany, and Deutschland 89, when I, the aspiring agent, was studying Russian in college. Oh, the life I could have lived, running agents, blackmailing Communists, amassing compromising information… OK, I did make a career of that last bit, but the Commies got off easy.

Martin Rauch never wanted the life that I dreamed of, and apparently there will be no more seasons because, as the series finale seems to indicate, Donald Trump and his talk of a big, beautiful wall brought things full circle. But at least I got to watch this show. I streamed it on Hulu.

What I’m listening to

This week we’re adding Editrix to The Experiment’s Spotify playlist. Editrix is Wendy Eisenberg’s latest project that Stereogum calls “a skronky, chaotic take on DIY indie-pop.”

“Tell Me I’m Bad” squirms and wriggles and skitters without ever veering off into experimental noise-rock territory. Instead, the band uses those sounds to spike a straightforward, hooky song about vulnerability. Even amidst the storm of sounds, Eisenberg’s voice has a nice conversational quality to it. Good song!

We here at The Experiment dig music that pushes us a little out of our comfort zones. This is not The Happy Fits or The Thermals, but it’s smart lyrically and musically.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

If your new year’s resolution was to lose weight, try Noom, and you’ll quickly learn how to change your behavior and relationship with food. This app has changed my life. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works.

Headspace is a meditation app. I’ve used it for a couple years and am absolutely shocked at how much it’s taught me about managing my inner life. Try it free for a couple weeks. Don’t worry if you’ve never done it before. They talk you through it.

I now offer personal career coaching sessions through Need Hop.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had.

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.