The rain in Spain falls mainly in your brain

The surprising science that explains how Audrey Hepburn can change your future

One of the things I’ve loved about moving to Dallas is reconnecting with Mary Beth Rogers, who gave me my very first job in Texas as a deputy press secretary for Ann Richards’ re-election. We’ve gotten together periodically to talk about all the things we’ve been wrong about over the years. There’s no sense lying to her. I don’t believe I could lie to a person who put up with me when I was 24.

Mary Beth stepped off a curb not too long ago and messed up her foot. Surgery went well, but the recovery has been tough. To paraphrase the poet Maggie Smith, though, she’s kept this from her children. She tells them everything’s fine and that she’s feeling better all the time. “You gotta have two stories, Jason,” she told me when we had lunch last week.

Dr. Paul Zak, a professor of neuroeconomy at Claremont Graduate University and one of most cited scientists in the world, would disagree. His research discovered that when we’re told a good, emotionally engaging story, our brains synthesize the neurochemical oxytocin, A.K.A. the love hormone, “and that the molecule motivates reciprocation,” he writes.

I now consider oxytocin the neurologic substrate for the Golden Rule: If you treat me well, in most cases my brain will synthesize oxytocin and this will motivate me to treat you well in return.

What surprised me about this is that our brains are lazy and don’t want to do this. They’d like to stick to the paved pathways, which requires less energy. (Even your neurons don’t want to go to the gym.) That’s why it takes a good story to fire the electrical impulses, flood the zone with oxytoxin, and build new neural pathways. As neuroscientists say, neurons that fire together, wire together. We feel great when this happens, but our brains have their hands on their knees, trying to catch their breath. This is hard work. In Zak’s words, this process is “metabolically costly.”

Your brain knows that’s Audrey Hepburn while it’s falling in love with Eliza Doolittle.

While all this is going on — you’re watching a movie and getting emotionally attached to Eliza Doolittle’s elocution, for example — your brain is keeping tabs on the environment. Wife didn’t see me cry? Check. Don’t need a refill. Check. No sabertooth tigers behind the couch? Check. Because of this, “the oxytocin response lags behind the attentional spike as the story begins.” Your brain lets you feel the love hormones on a tape delay because first it’s gotta check that you’re safe. You call it getting caught up in the story. Neuroscientists call it “narrative transportation.” Your brain knows that’s Audrey Hepburn at the same time it’s falling in love with Eliza Doolittle.

It seems that once we are attentive and emotionally engaged, our brains go into mimic mode and mirror the behaviors that the characters in the story are doing, or might do. As social creatures we are biased toward engaging with others, and effective stories motivate us to help others.

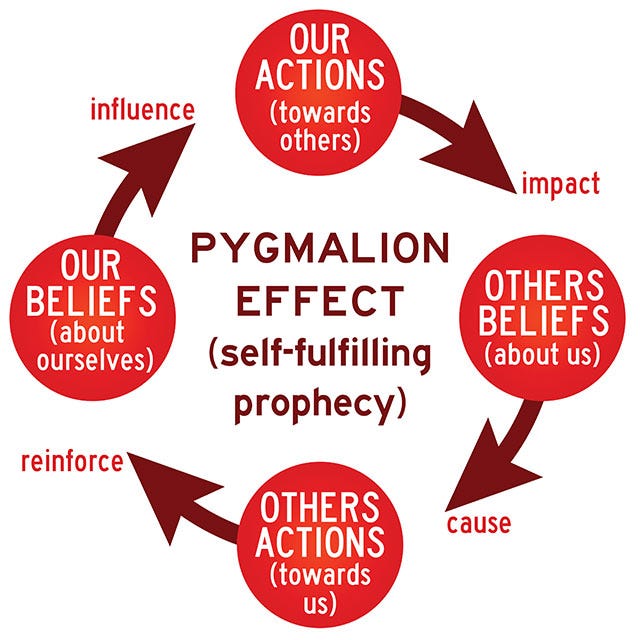

But what if it’s not a movie? What if it’s a teacher who is told that little Gloria is gifted and Anne is just ordinary? Any teacher knows that kids rise to their expectations, but it took a couple academics to overcomplicate this with research into what they call the Pygmalion Effect.

If you overlay the Pygmalion Effect on top of Zak’s research, you can see how a compelling narrative that includes the listener would influence their actions, which would affect how others perceived the listener and change their behavior toward that person. If I can convince Gloria’s homeroom teacher that she’s primed for an intellectual growth spurt, that teacher will treat Gloria as if she’s smart, which will change how Gloria thinks about school, give her more confidence, and result in better grades.

Conversely, you can tell your country that they are experiencing “American carnage” and that it’s the United States versus the world, and buddy, the world’s been winning. You can tell them that Libertas is a liar. Your tired, your poor? Your huddled masses in Muslim countries and in Mexico? The homeless and tempest-tost? They can get bent, because you know who the victim is here buddy, don’t you? Yeah, you get it.

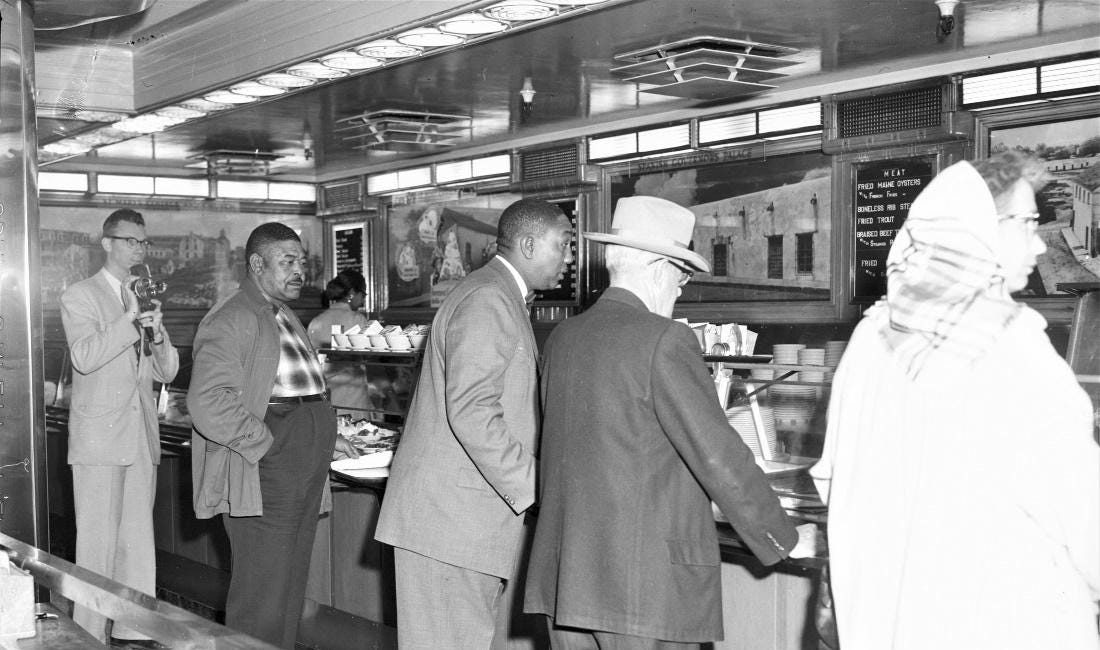

Or you can tell yourself a story that you want to become true, that we are a more perfect union, not perfect yet, or ever, but better than we were before because we are a country where we believe ordinary people have unalienable rights, including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And the story of our country is that pursuit.

We’ve seen those two stories in play lately. And we’ve seen what behaviors come from those who listen to either story. The stories we tell ourselves build new pathways to different futures.

We’re telling ourselves stories, too.

We’re telling ourselves stories, too, and not just about this country but about ourselves. Jon Acuff calls these soundtracks. I prefer to think of myself watching a movie about the story I tell about myself. The movie is always starring me (natch), and it’s changed over the years.

It wasn’t until recently that I realized I could change it on purpose. The movie in my head used to be a story about shame and guilt, and you’ll never guess how that effected my behavior.

Now I’m telling myself a different story, where the hero has met challenges with courage by turning shame into self-acceptance. It’s a superhero origin story, but with the emotions of a 53-year-old white dude. I don’t expect to sell many tickets.

Telling the story makes the story come true even if you know it’s just a story.

I’m confident that this story is going to lead to me being happier. And here’s the thing: I know I’m telling myself the story, and that I’m doing so intentionally to make the story true. The neural pathways that will lead to a better future for me would not have been built had I not chosen to tell this story. Telling the story makes the story come true even if you know it’s just a story. You know it’s Audrey Hepburn in the movie, but Eliza Doolittle is making you cry.

So let this be the only time I’m going to tell Mary Beth that she’s wrong. You gotta tell one good story. And hers is that she stepped off a curb and fell, but she’s getting back up and working on getting better all the time. She’s not even limping anymore.

The United States is celebrating Independence Day this week. What story are you going to tell about our country?

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the New York Times bestseller Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House.

Well that was very satisfying, Jason. Thank you. I will save my story about the US so as not to sully your Tuesday. PS I love how our brains can trick our brains even when we know exactly what we’re doing, but we let ourselves fall for it. (To clarify, I love this when it is being used in a positive manner, not, say, to convince myself—as I have sadly done too often— that obvious red flags are in “fact” glorious assets.)