"We had our brief flirtation with power, and then we lost it."

Mary Beth Rogers was my first boss in Texas, and she's still teaching me lessons.

Did I ever tell you how I ended up in Texas? I ended up in Moscow because I wanted to be a spy so I majored in Russian, but the Cold War ended. That meant I still had to do a semester in Moscow to get my degree, and one of the requirements of my study abroad program was to do an internship. I landed a gig as a copy editor at the English-language translation of Kommersant, a Russian business publication. My boss there was Billy Rogers.

Billy made a helluva impression on me. Hell, he made a big impression on everyone. I’ve written before about how we carried a dead body together. When cab drivers asked him where he was from, he’d explain in his broken Russian that he was from Austin, Texas. To give further context, he’d explain, “It’s near Dallas. Kennedy, bang-bang.” He always had stories about Texas politics and had ended up in Moscow because campaigns were only one of the addictions he was trying to outrun. Honestly, it was only in sitting down to write this that I realized how funny it is to go to Moscow to clean up.

Through a series of events that made sense at the time, we ended up being handed an English-language tabloid for expats called the Moscow Guardian. He returned to Austin in 1993 when Gov. Ann Richards appointed Billy’s friend Bob Krueger to a vacant U.S. Senate seat. On his way out the door, he made me editor-in-chief. I was 22, which made me just dumb enough not to notice just how out of my depth I was.

Krueger lost the special election to keep his seat — honestly, it was so bad people still argue over who is to blame — so a few months later Billy was back in Moscow consulting for the privatization effort, which turned out to be a big scam. By this time I had led an unsuccessful strike for unpaid wages against the Guardian — it really didn’t seem weird at the time — and was working as a researcher and stringer in the Los Angeles Times bureau where I magically ended up with a scoop about the diversion of privatization money to Yeltsin’s political party.

Billy did me one more solid on the way out the door when I got sick of being cold and sick of being a journalist. His mother, it turned out, had just taken over Ann Richards’ re-election campaign. “Why don’t you move to Austin and go to work for Ann Richards?” he suggested. So I did, but first I flew home to the Pacific Northwest and bought a black Volkswagen with black leather interior but no air conditioning. I knew Texas was hot, but I figured I’d be fine because the VW had a sunroof. By this time I was 23, but as it turned out, not another year wiser.

This is the unlikely chain of events that delivered me to Mary Beth Rogers, Billy’s mom and Ann’s campaign manager. My scoop, courtesy of her son, qualified me in her eyes as a researcher, so she installed me in the communications shop as a deputy press secretary. We were so overstaffed that our press office could have fielded an entire baseball team with a designated hitter.

“Chuck F*&%ing McDonald.”

My incompetence was eclipsed only by my overconfidence. Mostly I drafted press releases attacking George W. Bush for his lousy business record because, well, it was lousy. Bush had a series of oil companies, each one with some connection to his father’s financial supporters, but it turned out Bush couldn’t find oil if he went to Walmart. To try to get the newspapers to turn our press releases into articles, I would ghostwrite the meanest quotes for my boss, Chuck McDonald, which is part of the reason that he became known in the Bush campaign as “Chuck F*&%ing McDonald.”

When I wasn’t writing press releases, I would ghostwrite letters to the editor for supporters to sign. This was back when beepers and fax machines were called “high tech,” and letters to the editor were thought to roughly approximate audience engagement with a story. So if one of our press releases generated a story, the letters to the editor would “keep the story going.” A story keeps going long enough, and regular people might notice and ask whether George W. Bush’s business career was really just a series of tax shelters for his dad’s buddies.

Meanwhile, while we tried to generate some negative press for Bush, we didn’t have much of a positive one for the Governor. That wasn’t Mary Beth’s fault, or Chuck’s. Every Friday, the senior staff would trudge off to sit through another focus group of swing voters who said that while they liked the Governor a lot, they weren’t crazy about her appointing so many women and homosexuals and Black people and Latinos to cushy state jobs. And they were mad about juvenile crime, which was coded language, and welfare cheats, which was also coded language. And they were mad that the Governor had vetoed the bill that would have allowed them to carry concealed weapons. That wasn’t coded language. They really just wanted guns.

Ann Richards was one of the most popular politicians in the country, and Texans didn’t want to hear a damn good thing about her. And so every Friday, the senior staffers would trudge back into the office looking miserable. On particularly bad days, Mary Beth would send one of the staffers to the bakery for a big chocolate chip cookie. It wasn’t long before getting her that cookie turned into a daily errand. Mary Beth never gave up, but she didn’t smile as much.

Mary Beth was about to endure her biggest professional failure.

Mary Beth was as old then as I am now, and she was about to endure her biggest professional failure. Ann Richards’ loss to Bush hurt. On the day she lost, Ann Richards had 60% positive personal ratings, but we were never able to get over the fact that only 47% of Texas voters were willing to re-elect her.

I was a dumb kid then, 24 and still unclear on the difference between my butt and a hole in the ground, but Mary Beth was the boss. She managed the upset win in 1990, served as chief of staff during the heady first years of the Richards administration, and now presided over the end of Ann Richards’ legendary political career. It was, in her words, “humiliating.”

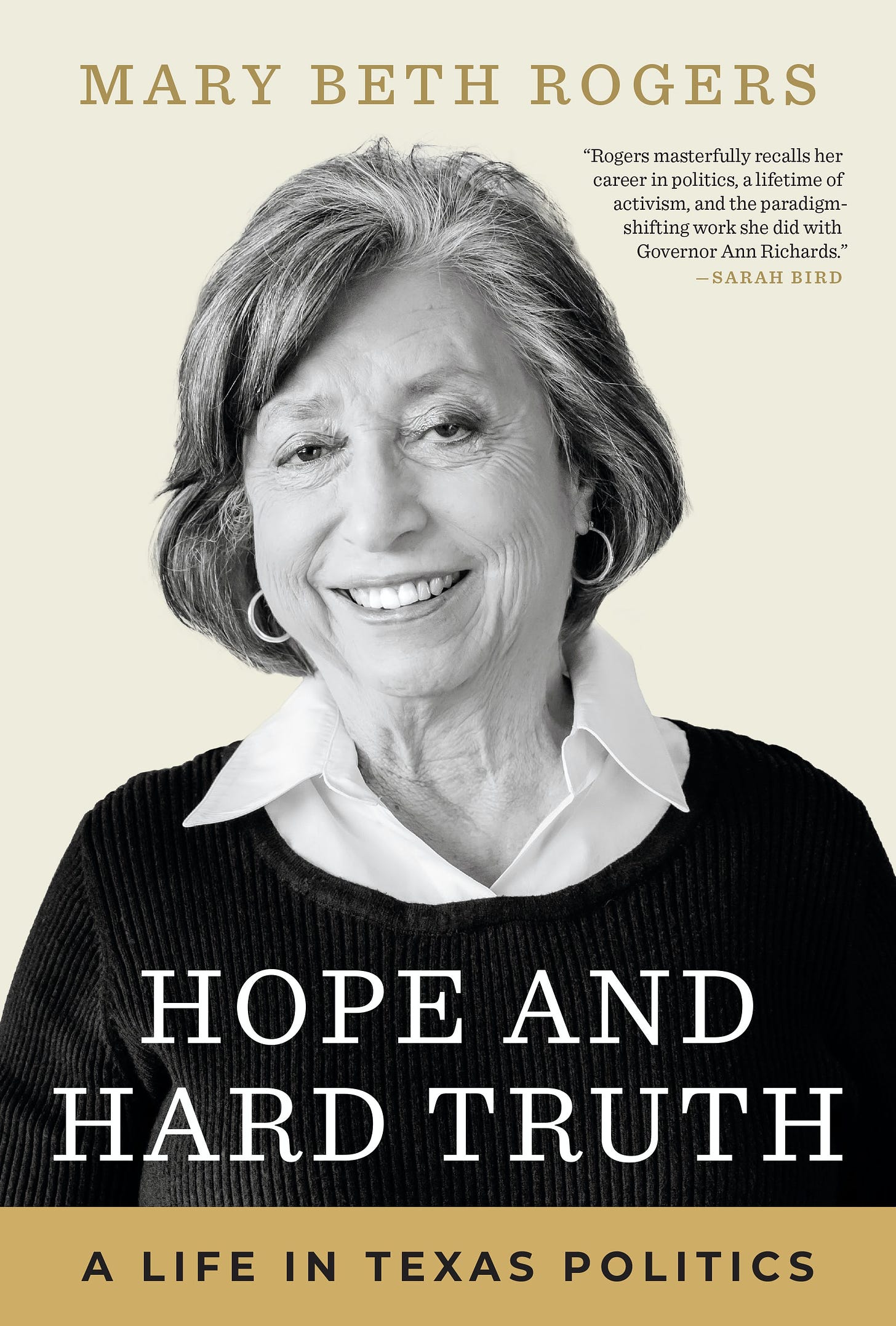

It took me years to stop feeling like a failure because of that 1994 race. In her new memoir, Hope and Hard Truth, Mary Beth admits to “hubris to think that I might be able to turn around what already looked like a problematic effort, just as we had been able to do in 1994. I was wrong.”

It took time for the shock of our defeat to settle in and for me to learn that what distinguishes a losing campaign from a winning campaign, apart from the obvious and immediate analysis, is how we remember it. Early on, it was the victor’s version of our defeat that readily absorbed my attention and guilt. After all, winners always get to write the history, and winning erases most of the mistakes and insanities encompassed in an election victory, while losing always exaggerates them. Because we had allowed ourselves to believe that our “brilliance” created our exhilarating victory in 1990, it would be natural to assume that our “stupidity” produced the disaster of our 1994 loss. If only it were that simple.

In time, she accepted that larger forces — demographic change, a national backlash against Bill Clinton, and though Mary Beth doesn’t say so, I’ll add sexism to the pile — outweighed her individual mistakes. This is the paradox of her winning memoir: Mary Beth had as much impact on Texas state government and politics as just about any non-politician, but as her memoir makes clear, in the end none of us have much impact. In just a few months, George W. Bush had wiped out almost all of Ann Richards’ policies and accomplishments. Her book is both about a singular career and about the impermanence of everything we do. I’d quote Socrates here, but you get the point.

Billy came back into my life about a decade ago when he became a client of a consulting company I founded. Though it still bears my name, I left that company in 2014, but Billy’s still a client of that company, is doing well, and has been subscribing to this newsletter for more than two years. (Hey, Billy!)

Mary Beth has been a subscriber for even longer, which until recently I thought was the biggest compliment she could give me. Mary Beth came back into my life when she paid me what turned out to be the greatest compliment ever: She asked me to write a blurb for her book, and it wasn’t just because thanks to Forget the Alamo I was now officially a writer. It was, she says, because I’ve been involved with her family for so long and had been around for much of her story. All at once, it felt like all the different ages of me were sitting in the same room with her.

Yes, of course I cried.

And of course I blurbed her book.

It’s fitting that a woman whose career started by uncovering the untold stories of women who made history has become one of those women. If not for Mary Beth Rogers, you may only remember Ann Richards as the funniest teacher you’d ever met. And if not for this book, you would never understand how liberals once ran Texas. People here like to say, ‘God bless Texas.’ I say God already did, when we got Mary Beth Rogers.

I sent that directly to her publisher, which sent it to her. “UT Press sent me your endorsement for the book,” she emailed. “It made me cry for all the right reasons. If you ever put yourself up for adoption, I’ll take you in a minute.”

So now, at least when it comes to crying, we’re even. I’m looking forward to seeing her, and I hope Billy, too, at her book event next week at the Austin Public Library. You can get the details here, and you can buy the book here. I’ll be the one hugging Mary Beth.

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback now!

Good story!