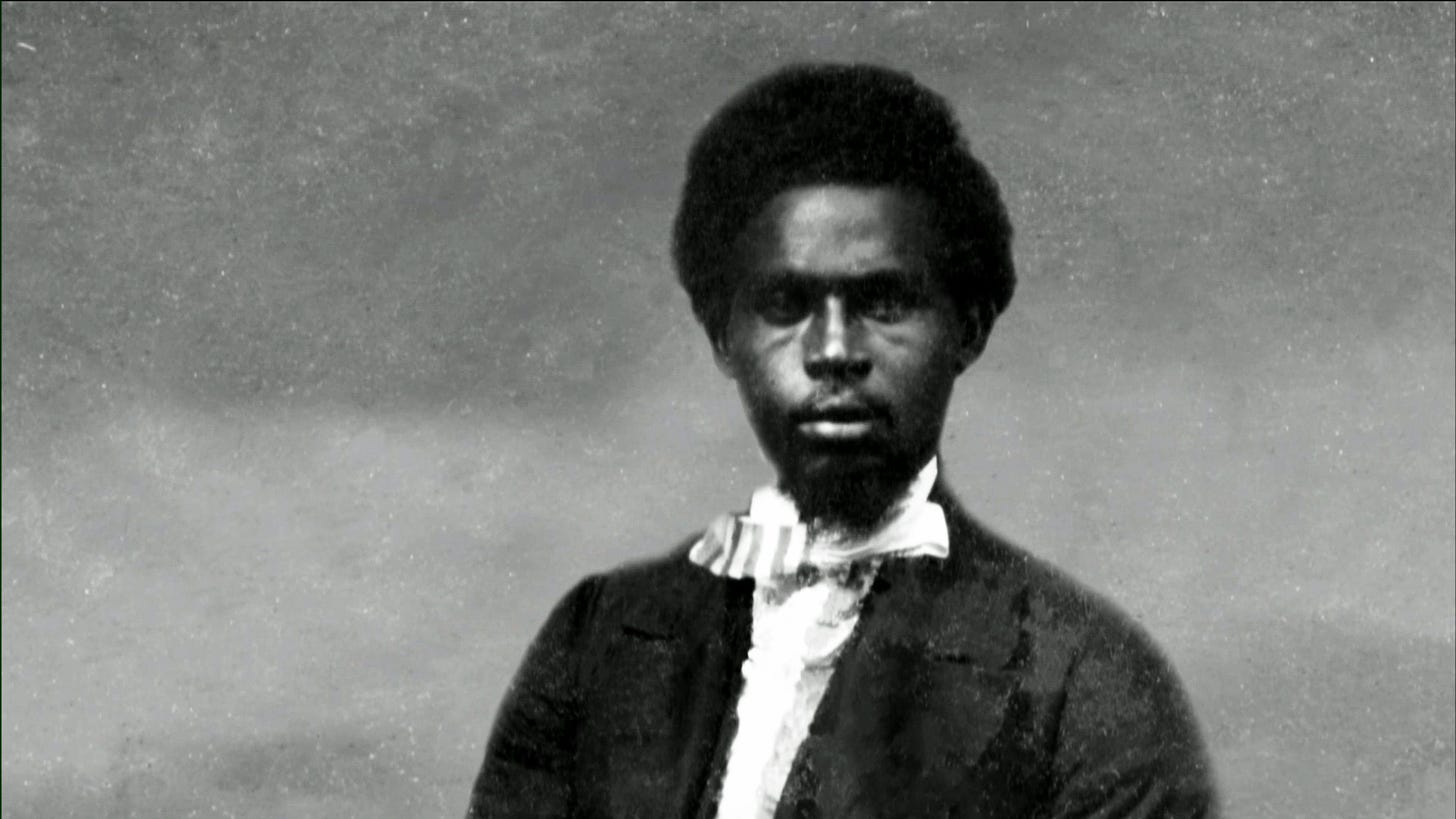

What if the Confederacy really did produce heroes… just not the ones that you think. Tom Ramsey, who last month told a strange tale of new love and near death, returns to mark Confederal Heritage Month by remembering a real hero, Robert Smalls.

by Tom Ramsey

Tate Reeves, the governor of my former state of residence and the state of my birth has continued the ignominious “tradition” of celebrating the actions of the OG terrorists and traitors by declaring April in Mississippi as “Confederate Heritage Month.”

So let’s talk about a “Southern” hero of the Civil War.

In 1839, in a field behind the house of his master, Robert Smalls was born a slave in Beaufort, South Carolina. As a child, he and his family toiled under the brutal laws and norms of South Carolina slavery. At the age of 12, and at the urging of his mother who held sway with her master, he was sent to Charleston to work as a “hired laborer” with his master receiving a “rental fee” for Smalls’ labor. Smalls was awarded one dollar per week, more money than he had ever seen. Young Smalls was drawn to the sea. He worked as a longshoreman, a sailsmith, a rigger, a deckhand and eventually as a wheelman. His time on the sea, navigating the waters of Charleston Harbor and beyond and learning the signal codes of his Captains trained him for his destiny.

In 1862 he and seven other slaves were pressed into service aboard the ironically-named CSS Planter, a Confederate gunship guarding the port of Charleston. Gen. Roswell Ripley declared the ship a “first class and formidable coastal steamer.” The former hauler of cotton and human cargo now bristled with six guns, including a 32 pound pivot gun and a 24 pound howitzer. In its hold were over 200 rounds of ammunition.

The crew of eight slave Sailors, two white officers and one white Captain were aboard as she docked in Charleston harbor on the night of May 12th. For a fortnight she had supplied the garrisons around the harbor, which was blockaded by the Union Navy. They also had taken aboard a battery of guns from a decommissioned confederate post on Cole’s Island. The Captain (CJ Relyea), the Pilot (Samuel Smith) and the Engineer (Zerich Pitcher), weary from their works and longing for good food, drink and comfort, decided to attend a party in town that night, leaving the slaves alone to guard the ship. Had the news of this action reached their command, the Captain and his white officers would have faced courts martial. They thought so little of their slave crew, they never imagined that they would be found out and even gave the crew permission to visit with their families on the docks that night. This was the moment Robert Smalls and the crew had been waiting and for. Smalls and the crew (save for one man “in whom they held no trust”) had previously planned an escape and created signals to inform their families when to meet them. Their families on the docks, the dangerous plans to run ashore and meet their wives and children were no longer needed. Robert Smalls, who had been piloting the harbor since the age of fifteen, and his fellow slaves took the ship without firing a single shot. At two AM, Smalls, a fair skinned Mulatto, donned the Captain’s uniform and white straw hat, hoisted the South Carolina and Confederate flags and sailed the gunship with six members of the slave crew (one stayed behind for fear of getting caught) away from the shore, pausing briefly at the end of the dock to pick up Smalls’ family and eight other slaves.

Around four AM the ship passes Fort Sumter. The crew urged Smalls to “swing wide” and not within easy view of the fort, but Smalls knew that would raise suspicion. Instead, he sails close enough to present the fort with signal flags indicating their intention to sail past. After a moment long enough to cause fear of a cannon blast, the fort signals “All is Well” and Smalls, standing at the wheel with his arms folded on his chest like the manner of Captain Relyea, calls to sound a blast of the ships horn as a greeting. He later recalled that he waved at soldiers awatch on walls of the fort, and received waves of greeting in return. In the moonlight they assumed he was white and were accustomed to see black sailors signaling with flags. Now, the Planter is sailing quickly toward the Union blockade at the mouth of the harbor.

Once beyond the range of Sumter’s guns, Smalls orders his crew to strike the Confederate colors and replace them with the white bedsheet his wife Hannah had stolen on wash day from the hotel where she was enslaved. The US gunship Onward sees the Planter approaching not the improvised white flag. The Onward opens her gun bay doors and rolls her cannons into firing position. Seeing this threatening activity, Smalls orders all the slaves to assemble on the starboard railing and “commence a commotion to bring attention to themselves and their dark skin.”

He commands the slave at the helm to move hard to port, exposing the Planter’s broadside with her guns unattended. Incredulous at the poor wartime tactic of a captain presenting his ship’s flanks, the Onward pauses her bellicose actions. As the sun rises, the captain of the Onward sees the slaves “whooping, singing and dancing” on the rail of the Planter and the bedsheet where the Confederate colors once flew. He issues to order to stand down and roll back the guns. The contraband steamer comes under the stern of the Onward, Robert Smalls takes off his hat and says to Lt. Frederick Nichols, “I’ve brought you some of the United States old guns, sir.”

With that greeting and it’s joyful reception, all souls aboard the Planter are free.

Had this been the end of the story, the tale of Robert Smalls would be significant, but what happens subsequently, makes him a legend.

The jack of the US Navy is hoisted above the decks of the Planter and she steams to Port Royal, on Hilton Head Island. Smalls is greeted as a hero and Flag officer SF DuPont, describes him in a letter to Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy, thusly: ““Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feet so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter guns], presuming it would be a matter of interest. He is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been.”

Admiral DuPont arranges for the safety of the newly free families and escorts the crew of the Planter to Washington, where Smalls is awarded $1,500 (a commission based on half the appraised value of the Planter) and an audience with President Lincoln. Smalls lobbies the President to allow for the enlistment of black soldiers in the war effort. A few months later, Lincoln does just that. Smalls is said to have personally recruited over 5,000 black soldiers to fight the rebels who once considers them as chattel.

Smalls participates in 17 naval actions against the rebels, including a “white hot” battle with Fort Sumter aboard the ironclad USS Keokuk which takes 96 “hits to the iron” and later sinks. In 1863 he returns to the Planter as its pilot. That December the Planter comes under heavy fire from the Confederate battery dug in at Secessionville. During that action, he assumes control of the Planter when his Captain becomes “shocked and demoralized” fleeing to the safety of the ship’s coal bunker. As acting captain, Smalls steams the wounded ship to safety, refusing to surrender. He fears a surrender will mean a return to slavery and harsh treatment at the end of the whip or worse, a noose. This valiant action earns Robert Smalls an official commission as a Captain in the US Navy and the $150 monthly salary that comes with the title. He is now the highest paid black soldier in the Civil War.

At the conclusion of the war, Captain Smalls steams the Planter into the Charleston Harbor, received as a hero by his peers in the victorious Union Army.

After the war, he took his $1,500 commission for the Planter and purchased the plantation home of his former master. He and Hannah moved into the master bedroom. His grandchildren are born inside the house, not in the duty field behind it. He founded the Republican Party of South Carolina and was elected to the South Carolina Legislature. There he authored the legislation that established the first free, public school. He later served five terms in the United States House of where he voted to keep Federal troops in the South, fearing the treatment of blacks if they were to leave. Military reconstruction ended and his fears manifested to reality. In the last 20 years of his life, the war hero, retired Navy Captain, former Congressman and South Carolina landowner was denied the right to vote.

In 1915, he died in his home accompanied by his family.

Between the passage of the 1895 laws that stripped him of his right to vote and ushered in the horrors of Jim Crow, he was a voice for the rights of his African American brothers and sisters. In a speech a few years before his death he asserted, “My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

So let’s do as Governor Reeves suggests. Let’s celebrate this “Son of the South,” his bravery and his legacy

Tom Ramsey is the chef at Atchafalaya Restaurant in New Orleans. Tom appeared on the premiere episode and the “Supermarket Masters Tournament” of Guy’s Grocery Games on the Food Network; made it to the quarterfinals on Season Three of ABC’s The Taste; and was featured on Appetite for Life and Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern. Follow him on Twitter at @ChefTomRamsey.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

If your new year’s resolution was to lose weight, try Noom, and you’ll quickly learn how to change your behavior and relationship with food. This app has changed my life. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works.

Headspace is a meditation app. I’ve used it for a couple years and am absolutely shocked at how much it’s taught me about managing my inner life. Try it free for a couple weeks. Don’t worry if you’ve never done it before. They talk you through it.

I now offer personal career coaching sessions through Need Hop.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had.

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.

As a daughter of the South I find Captain Robert Smalls to have been an extraordinary man who is a valuable exemplar for any American human being. Thank you for retelling his story. I am grateful for you for his tale.