The Howard Beale of Texas

Meet the reporter Dan Patrick banned from the senate and tried to get fired

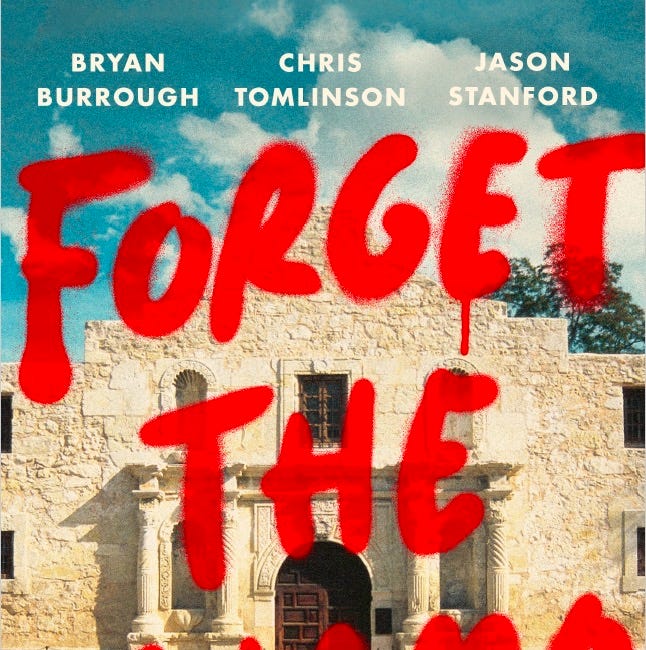

Welcome to the always free, reader-supported weekend edition of The Experiment. If you’d like to support my work, buy my Alamo book, buy some Experiment merch, drop some coins in the PayPal fountain, or become a paid subscriber. But even if you don’t, this bugga free.

There is the way government of the people, by the people, and for the people is supposed to work, and then there’s the Texas legislature. The Governor had called the legislature back into a special session — again — to raise teacher pay, subsidize private school tuition, and to keep out immigrants. If you think those things would look good on a mailer in a Republican Party primary, you’re getting the idea.

Late in the afternoon of Nov. 9, the Senate Finance Committee called a meeting to pass out two of those bills — money for schools and border security — that day. Texas has more children attending public schools than most states have people, and we are experiencing a genuine humanitarian crisis at our Southern border that the Yahoo caucus of the Republican Party insists on seeing as a criminal invasion rather than huddled masses yearning to breath free. These are huge issues affecting millions of people and billions of dollars. The whole meeting took 10 minutes and included no public testimony or any real discussion by the senators.

That was by design. Instead of being scheduled to allow people to come to Austin to testify, the committee meeting was called minutes beforehand and held in the press conference room outside of the Senate chamber, not in a committee room with, you know, chairs for people and a dais for the senators. Holding the meeting in the press conference room meant the senators had to sit in the reporters’ seats, forcing what few reporters lucky enough to find out about the meeting to stand against the wall.

“Pure chaos,” tweeted Sergio Martínez-Beltrán from NPR.

“They just asked for public testimony but there’s none because this meeting was not previously announced,” he tweeted.

“It's a great public policy afternoon,” tweeted Sen. Bettencourt, who took less than four minutes to describe his school finance bill. Both bills went to the senate floor, where they took a whole 25 minutes to pass them both.

A little after 10 that night, Scott Braddock, a Texas political journalist, quote-tweeted Martínez-Beltrán’s observation from earlier that day. “It’s not chaos. It’s streamlined undemocratic pre-fascist governing with no regard for process.”

When I saw that tweet the first time, I got hung up on “pre-fascist,” strong words from a mainstream journalist, but to Braddock, the process is the priority. Things aren’t supposed to work this way. “I'm talking about journalists who are maybe covering their very first legislative session and they wonder whether this is the way this is supposed to happen, and so I had publicly reminded folks that it wasn’t chaos,” he said later.

“It’s not chaos. It’s undemocratic pre-fascist governing with no regard for process.”

In 1993, Texas taxpayers shelled out $75 million for extra space in the Capitol in part to ensure they’d always have enough space in hearing rooms so people could see what their government was up to. Holding a hearing in a room with no time for people to get there and no room if they did was a choice. “The abuse of the process and of that physical space is deliberate,” he said.

Scott Braddock is mad as hell, and he’s not going to take it anymore. He’s leaning out the Overton Window and shouting about process, making him the Howard Beale of capitol press corps.

A former political reporter for radio news stations in Dallas and Houston, Braddock was fired in 2013 after he interviewed a woman who had just had an abortion to find out about her experience with the invasive requirements of the state’s new sonogram law. His firing drew condemnation across the political spectrum, including from anti-abortion groups who thought his show offered a fair forum to all comers. That’s nice, but Braddock was 33 and had a kid to feed and rent to pay.

“The abuse of the process and of that physical space is deliberate.”

Harvey Kronberg, the owner of the Quorum Report, a 40-year-old digital news outlet covering the Texas government, saw an opportunity. “I took a look at him because he was about information, not inflammation,” said Kronberg, who allowed that Braddock “brings the sharpness and thick skin that talk radio provides.”

Kronberg hired him part-time. Soon, he named him editor. Braddock also co-hosts the Texas Take podcast with the Houston Chronicle, but for the last decade Braddock’s been the face of the Quorum Report, covering what happens inside the pink dome for the people who work there. As Braddock puts it, “I run the community newspaper for the Texas capitol. The primary thing that I do is to be the memory for the building.”

Over the last decade, thanks to layoffs and key retirements, a lot of the institutional memory has left, leaving Braddock, only 43, as one of the elder statesmen of the capitol press corp. “There’s no doubt that he’s become the journalistic face of the legislature, especially as the press corps has been hollowed out,” said Kronberg.

There are, of course, other veteran Texas reporters who know that what passes for normal today would have caused a scandal not long ago. “But they don't call it out in the same way,” said Braddock. And it’s that positioning that rubs some of his colleagues the wrong way. Tradition-minded journalists who learned their craft on manual typewriters are not universally enamored with Braddock. If journalism were the Catholic Church, these people would still be writing in Latin, and they consider it a cardinal sin to abandon their dispassionate remove and to enter the story. More than one, speaking on background, accused Braddock of this, especially when it comes to how he engages on social media.

“He acts more like someone on the field of play instead of an observer,” said one. “That’s a style mistake, in my opinion, and it’s a substantive mistake in his craft, because it limits who’ll talk to him and thus limits what he knows.”

“No journalist should ever be engaging like this,” said another.

Perhaps it’s a mistake, though, to find fault in Braddock’s failure to conform to the religious order of mainstream daily journalism. One journalist whose career started during the Carter administration took a broader view of Braddock, who cut his teeth in talk radio “where provocation and argument is part of the act” and is now at a political newsletter which are expected to reflect the personality and point of view of the writer. “He’s landed in a place that suits the way he does this,” said this journalist.

“He’s landed in a place that suits the way he does this.”

Yet another journalist, surveying the diluted ranks of the Texas press corps, saw Braddock as occupying yet another role. “We don’t have a Molly Ivins anymore,” this journalist said, “and there’s no opinion columnist sitting at the press table.”

Braddock gets big mad about small things. He criticized former Speaker Dennis Bonnen in a column for procedural inconsistency and cited Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick for “ending decades of Senate tradition” with “brute force” that valued the Republican majority over consensus “implosion of an institution.” More recently, Braddock called the special sessions for school choice Abbott’s “legislative Vietnam.”

Braddock has found a way around both-sidesing every story where every Republican misstep has to be counterbalanced by a Democratic counterfactual. (See also: Why don’t Democrats save congressional Republicans from their latest Speaker crisis?) In Texas, Republicans control everything but the A/C in my home. The drama in Texas isn’t Democrats versus Republicans but Republicans versus normal, and perhaps no one has done more damage to the regular order of business than Patrick, the 73-year-old former talk radio host who was one of the first Texas politicians to back Donald Trump.

Braddock used to get along with Patrick. In the beginning, they were competing talk radio personalities in Houston, and when Patrick made the transition from behind the mic to behind the podium, Braddock enjoyed a productive working relationship with him. “We didn't have any issue at that time,” remembers Braddock. “He would often say that I was generally fair, but I might’ve written some things he didn't agree with.”

“That all changed when he became the Lieutenant Governor,” said Braddock. “He was always looking for some excuse to ban or punish me somehow.” He credits the troubles he had with Patrick and then-Speaker Dennis Bonnen to what he calls “calling out their abuse of the process.”

“That all changed when he became the Lieutenant Governor.”

But it was the tweet that did it, and to be fair, it did not reflect well on Braddock.

In the 2019 legislative session, a Republican senator got crossways with Patrick, which led the lieutenant governor’s mouthpiece, the famously acerbic Sherry Sylvester to make an impolitic remark in public about the senator.

“I have a recommendation for Miss Sylvester,” tweeted the senator, “her lips and my back end.” The senator lost his committee chairmanship in the process, which drove Braddock to Twitter to post that the senator’s juvenile suggestion “was the nicest thing anybody could say about her.” At least, that’s what Braddock thinks he tweeted, since he quickly deleted it after Kronberg, a longtime friend of Sylvester’s, told him to take it down.

What happened next has never been reported before. Later that night, Kronberg got a call from Patrick, who expressed condolences for Kronberg’s late wife before telling him that he fired someone who did what Braddock did. Politicians calling editors to whine about reporters isn’t worth mentioning, but this was the first time a politician had ever called Kronberg to bully him into firing one. For that matter, Kronberg has never heard of this ever happening in the capitol press corps.

“I told him worked for me. And I’m not going to fire him.”

“But we haven’t had a personality like Dan Patrick before, either,” said Kronberg, who told Patrick, in so many words, to pound sand. “I told him he didn’t work for Patrick. He worked for me. And I’m not going to fire him,” said Kronberg, who remembers that Patrick told him that Braddock was not going to lose his press credentials but would be banned from the Senate floor and the back hallway where credentialed reporters had always been allowed.

Braddock says that the next day the Sargeant of Arms, the staffer who manages protocols in the senate, told him that Patrick said, “I don’t wanna see this guy on the senate floor, and if he’s out here, there’s gonna be problems.”

Now, understand that “senate floor” is a term of art describing the area behind a brass bar that makes a u-shape in the senate. Inside the bar are the senators, staffers, and credentialed press. Outside of the bar are lobbyists, more lobbyists, and now Braddock, who had no problem reporting as long as his mobile phone got reception.

To Braddock, the real problem was that the Lieutenant Governor, whose powers are derived from the senators and written out in processes, was ruling by fiat. “He was doing what he does with everyone who crosses him, but I’m convinced that when he banned me he was also testing what he can get away with.”

“I’m convinced that when he banned me he was also testing what he can get away with.”

Obviously, I have some experience being banned by Patrick, but when he ordered the Texas state history museum to cancel a virtual event for our book, it got national news. The Washington Post asked me to write an oped about it. The publicity over the controversy caused sales to skyrocket, and we made the New York Times best-seller list. Though I remain opposed to government censorship, in my personal experience getting banned by Dan Patrick rules. 10/10, would recommend.

But when Braddock lost access for an ungentlemanly tweet — in my mind a more serious act of censorship — no senators objected. For that matter, not a single article was written about Braddock getting banned. A metro columnist for the Austin daily, Ken Herman1, eventually wrote about it, calling it a “dangerous, petty and thin-skinned move.” Braddock tried to wave Ken Herman off the column, though, saying, “The reason for that is I don’t think it’s appropriate for the journalist to become the story. I cover the news. I don’t make the news.”

Asked how he felt about not a single member of the capitol press corps speaking up in protest, at least publicly, he said, “I don’t think it’s anything personal about me.” He speculated that the remaining reporters didn’t want to lose access. After all, there are only so many seats at the press table on the senate floor. And Braddock’s seat was filled by a writer for a rightwing think tank funded by major Republican donors.

“I cover the news. I don’t make the news.”

At the time, the House was holding the line against giving these non-journalists press credentials, but the then-Speaker’s hold on power wasn’t the strongest. Looking ahead to the Republican primaries, Speaker Bonnen was ready to make a deal. In secret recordings made by the leader of that organization, the Speaker offered them a seat at the press table in exchange for their endorsing his slate of primary candidates. As to whose seat they would take, well, you can guess by now, can’t you?

Bonnen: “Let me tell you what I want to do. … If we can make this work, I’ll put your guys on the floor next session. And here’s what I will do: I’ll do what [Lt. Gov. Dan] Patrick did. I’ll take [Scott] Braddock off.”

Those secret recordings are a big reason Bonnen is no longer speaker, but soon, no one would be at either press table. When the legislature came back into session in January 2021, vaccinations were just barely rolling out. Everyone thought it safer if no press at all were huddled around the press table for hours on end.

And despite the retrograde blowback to vaccinations and masks, the senate carefully controlled access. To get into the senate chamber, you needed a wristband to show you had tested negative that day. People generally agreed with that precaution. On all other matters — critical race theory, banning abortion, censoring history — there was not a lot of agreement, and relations between the House and Senate were cranky.

So it wasn’t terribly surprising that the new speaker, Dade Phelan, was denied entry to the Senate chamber late on May 26, a scooplet that Braddock posted on Quorum Report shortly before midnight and went to bed. Apparently, Phelan didn’t want to wear a wristband.

“There was an agitator in the media…”

The Senate kept working for a few more hours. Shortly before calling it a night at 3am2, Patrick took to the mic to deny the report. “Members, I want to just get something on the record and clear something up. There was an agitator in the media earlier that said Speaker Phelan was denied entry to the Texas Senate because he lacked a COVID test or vaccination wristband. … The Speaker is always welcomed here.” Essentially, Patrick confirmed every detail of Braddock’s report while denying it entirely.

“That next morning I woke up to all these text messages from people who were calling me an agitator in the media,” said Braddock.

Soon, thanks to the spread of vaccines, the House voted to allow the press back onto the House floor.3 The press table in the Texas senate remains empty.

It’s important for Braddock that you notice something. When Patrick et al criticize him, they call him a liar, not a liberal. That’s because Braddock’s readers, sources, and subjects all work in the same building in downtown Austin where everybody knows Braddock is no liberal and, more importantly, that his sources are mostly Republicans who also are offended at the violation of norms but who would lose their jobs if they spoke up.

“The intended audience is people at the capitol.”

“When he lashes out at me and calls me a liar, the intended audience is not the general public. The intended audience is people at the capitol. If he called me a liberal, they would know better than that. So that won't fly,” said Braddock. “You saw this during the impeachment trial of the Attorney General.”

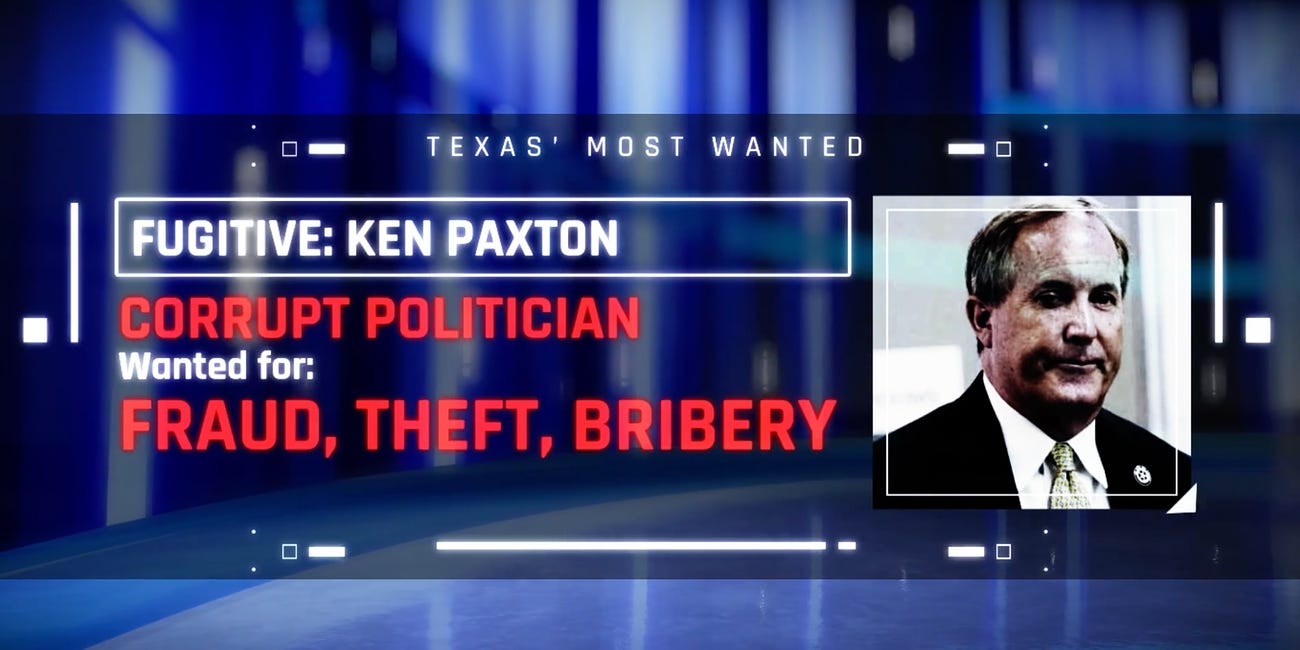

Earlier this year, the House impeached Attorney General Ken Paxton for doing so much corruption even people in Texas thought it a tad excessive. He even asked the legislature for millions of dollars to settle with whistleblowers, basically asking taxpayers to bail him out for ripping them off in the first place.

For a while, it seemed like the Senate might convict Paxton even though Patrick, who would preside over the trial, received $3 million before the trial from Paxton’s biggest donor.4 In fact, Braddock says six sources called him, all Republicans, to say that Patrick, as Braddock tweeted, “*may* be back-channeling to Paxton that it won't go well for him in the Texas Senate and to make it easier on everyone.”

“Wrong! I will never stop fighting for the people of Texas and defending our conservative values,” responded Paxton.

“Whomever5 is starting these false rumors needs to get a life,” said a Paxton defense attorney.

“Braddock is a flat out liar.”

Soon, the senators heard all the evidence. Well, not all the evidence. Somehow his mistress who quite literally was a corrupting influence was not deemed relevant and thus excused from testimony. Oh yeah, Paxton’s wife is a senator and was sitting right there the whole time during the trial. It was a whole thing.6

Before they went into deliberation, Patrick, as judge, told them they weren’t to talk to anyone, not even their families, about deliberations. Presumably, that applied to Patrick as well, as it would in any jury trial, but sources told Braddock that the Lieutenant Governor, or in this case the judge, had talked with Senators, or jurors, before they finished deliberations.

After Patrick publicly predicted Paxton would not be convicted — odd behavior for a judge, that — Braddock tweeted, “Now that he's speaking his mind about it, maybe would like to refute reports from members that he was calling senators last night asking them to vote no on the impeachment articles.”

Less than an hour later, Patrick responded.

“Another absolute made up story from Braddock,” he tweeted. “Two Senators called me about procedural issues and I called them back. I have not talked to one Senator about anything related to the trial unless it was a rule question from them. Braddock is a flat out liar.”

“Another absolute made up story from Braddock.”

So, in effect, reports that I’m talking to Senators are completely made up, except that I did. A subsequent investigation by the San Antonio newspaper found that Patrick had talked to two senators a total of three times. I’m sure it’s a coincidence that these two senators were thought to be open to voting to convict, though their votes would still not have been enough.

“I guess we're all supposed to believe that he didn't threaten them or lean on them to vote a certain way,” says Braddock now.

As much as he sticks up for the normal process, he’s comfortable that he’s not a normal journalist. Instead of emailing a flack for a statement that he knows he won’t get, he shares what sources are telling him on conservative radio or on social media to provoke a response from the politicians. He knows that if he acted normally, he’d probably have more access and would get his questions answered at press conferences. But if he weren’t doing what he’s doing, no one would be sticking up for the process.

Braddock likens the situation with the evolving news media to chess. Each piece functions differently on a chessboard. Knights and rooks move differently, as do kings and queens, pawns and bishops. It’s the same way with the capitol press corps. The daily news reporters have one function, the television reporters another. Some news organizations have stronger political leanings, some have a more niche focus.

And then there’s Scott Braddock, part talk radio host, part insider newsletter editor, part very online political reporter, part podcaster, part opinion columnist who sometimes, despite his best of intentions, becomes part of the story.

“Maybe I’m a different kind of piece,” he said.

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Threads at @jasonstanford, or email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!

In the interest of full disclosure, Ken Herman also once wrote a column speculating about my sex life. So his judgment is not flawless.

Patrick’s “agitator” remarks begin after the 6:05 mark here: https://tlcsenate.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=49&clip_id=16262.

Only one representative, Jared Peterson, voted against it. When Braddock asked him why he voted against re-admitting the press, Peterson said, “Because the Tribune’s too liberal,” referring to the digital-first, nonpartisan, independent news organization that, if anything, is too both-sidesy.

This is legal in Texas. The fact that it’s legal is the real corruption.

Whoever, not whomever.

Ryan Murphy, please make a Netflix movie about this.