Back when I was a cub reporter for an English-language weekly for expats in Moscow, we used to take note of the rot. Things — elevators, escalators, even empires — fell into disrepair and stayed there. Someone would put up a sign saying “ремонт,” which literally meant “under repair” but really meant the opposite. The sign was more aspirational than informative, and Russians would make do without complaint because no one expected things to work. We looked around at the state of things and concluded that we had been scared of this country for no reason.

“The Texas Rangers could take over this country in a week,” my editor Billy said once. He clarified that he meant the baseball team, and not the law enforcement agency, but to be fair, Nolan Ryan had more no hi-hitters than Vladimir Lenin and packed a nastier punch.

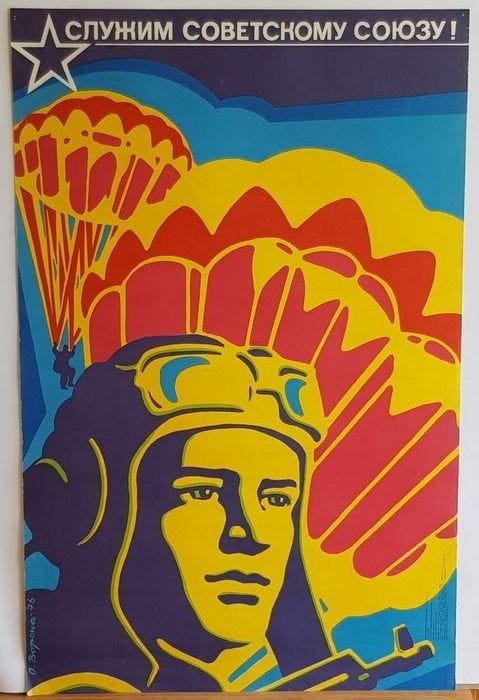

It was with this fundamental lack of respect in post-Soviet infrastructure and scorn for the Russian character, which is whatever the opposite of a can-do attitude is, that I decided to jump out of a perfectly good airplane.

I was assigned to cover a charity parachute jump that was to raise money for the children of Chernobyl. The idea was to get westerners to fork over dollars to parachute outside of Moscow. That the money would ever get to the juvenile victims of the nuclear catastrophe was assumed to be a scam, but it would have been impolite to focus on the petty larceny. For me, the story was a lark, and I thought there would be no better way to cover the parachute jump than to participate in it.

What could go wrong? I remember asking. After all, we were using military equipment with round chutes that opened automatically, not those daredevil rectangular ones that you opened yourself after free-falling. Just step out, it opens, you float harmlessly before gently touching down as if kissing the face of an infant.

I was 22 and an idiot.

There were several warning signs. I noticed not a one. My coworker who was in the Navy Reserves didn’t go. Training consisted of jumping off a picnic table. I paid close attention to the secondary chute but must have tuned out the bit about having to pull down on the straps to slow down before landing. To tell the truth, I was more concerned about whether I would find the courage to step out of the plane at all. One of the reasons I was doing this, you see, was to get over my fear of heights.

When I was much younger, my dad lived in Miami and had friends who owned one of Al Capone’s old houses that had a pool with the deepest deep end I’d ever been in. I was fine in water and even enjoyed swimming and snorkeling in the ocean, but that deep end with its bottom too deep to pick up pennies scared me. I jumped in, judged the situation too big for my little boy brain, and GTFO’d.

That’s exactly what it felt like in the seconds between me stepping off the plane and the chute opening. The sky was too big, and then the chute opened with a snap and I hung there in the sky, not liking things one bit. I wanted to be on the ground, and soon. The firma the terra the better.

There was a bit too much wind for a parachute jump that day, and people landed far from the landing zone. We were jumping in an area with a lot of dachas, or summer cottages, around the airfield and jump zone. In fact, someone landed on a dacha. Someone else landed on a cow. I landed in a grassy field near the dachas and far afield from the people collecting the parachuters, and I did so at full speed, breaking my right leg just above my ankle in three places.

And there I lay. People came out from their dachas to see what all the yelling was about. A babushka brought me a bowl of wild strawberries. One dude wearing nothing but a turquoise Speedo hung around for a while. After 45 minutes, the jump organizers came to fetch me. I asked if they didn’t know where I was. “No,” one said. “We could hear you yelling.”

They took me to the Kremlin orthopedic hospital in Moscow. There was a cabinet secretary there, so I figured they knew how to set a broken leg, and besides, it was the best orthopedic hospital in 11 time zones. What could go wrong?

I was 22 and an idiot.

Because so much time had elapsed before they could set my leg, it didn’t set right. I was fine as long as I was laying down, but the pain when limping to the bathroom to pee still haunts me. They gave me a shot of morphine and told me they would reset my leg in the morning.

My only memory from before they reset my leg was the anesthesiologist, who was young and had a unibrow. He told me to countdown from 10, and the next thing I knew I saw a gauzy, yellow light and could year someone yelling. The light became clearer, whiter, and I realized I was the one yelling. It’s hard to have a coherent thought when coming to while in pain, much less in Russian, but I managed to ask the anesthesiologist to knock me back out.

“Be quiet,” he said. “It’s almost over.”

While they were putting the cast on, a stout, older nurse criticized me for not bearing up more stoically. “You were really making a lot of noise,” she sniffed.

When it came time to have the cast removed, I had at long last learned my lesson and flew to Portland to have it taken off at a proper hospital. The doctor told me that if they’d set my leg they would have used a metal plate and two screws.

The Russians had just shoved it back together, putting my fibula almost in the correct place by my ankle. Consequently, I’ve had two rounds of arthroscopic surgery, and my right ankle is 100% cartilage free. I cannot run and can’t walk for long without pain. In a zombie apocalypse, I’m a goner.

The eventual uselessness of my right ankle happened much later. At 22 I imagined a full recovery. I was, not to put too fine a point on it, an idiot. But I did notice something curious. Several medical students were dropping in to see my ankle.

“What’s the deal?” I asked the doctor. “It’s just a broken ankle.”

“No, you don’t understand,” he said. “We haven’t seen a cast like this since the Civil War.”

Now in my fifties, I’ve had enough. I’ve scheduled a visit with an orthopedic surgeon for next month. The next step is to have my ankle fused, which they say will take away all the pain without decreasing my mobility. I’m sure if I thought about it I could find ways in which I have benefitted from having a useless right ankle, but none have come to mind in the last 30 years.

I can say, however, that there is more than one recorded song about this whole story, and I’ve embedded them above. That’s probably more songs about my right ankle than about perhaps any ankle of either side in human history. So I’ve got that going for me, which is nice.

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback now!

"In a zombie apocalypse, I’m a goner."

Perfection.

If I ever "jump" out of a plane, I am going to be strapped to the back of some dude who looks like The Rock. That said, your bravery is inspirational. So you've got that going for you too, which is nice.