Welcome to The Experiment, where if 2020 was hell, 2021 is hell frozen over. After last week in Texas I no longer have to explain why I don’t like camping. Our ancestors didn’t create plumbing and electrical wiring and heated homes just to see humans live like cavemen for fun.

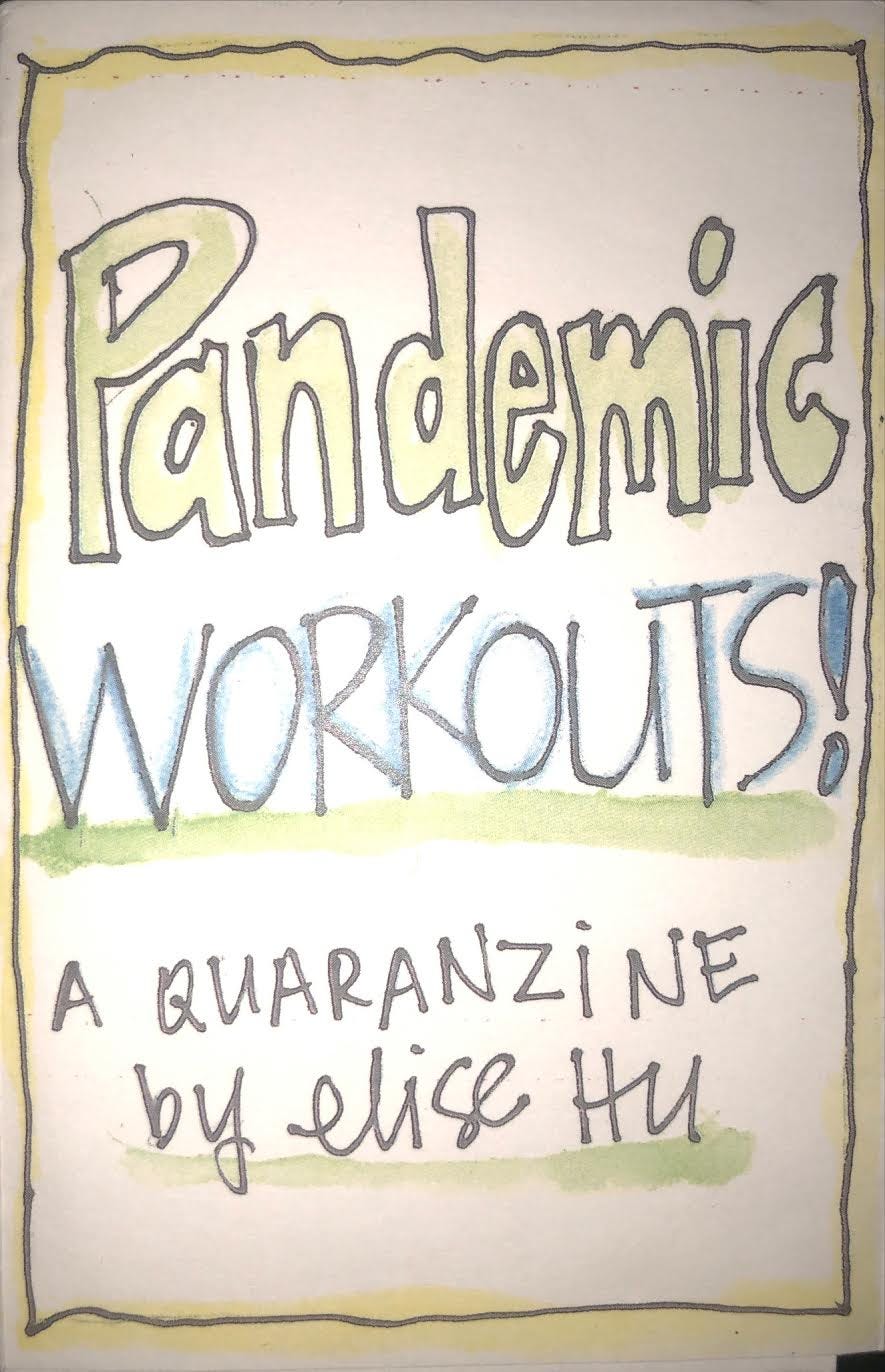

This week I talk to an Iraq War combat vet about our COVID-19 tour of duty and what he calls “the fallacy of being fine.” NPR’s Elise Hu makes her debut in The Experiment with “Pandemic Workouts: A Quaranzine,” and Jack Hughes returns with “Bidenfeld.” Will Kamala Harris be the next Elaine Benes or the next Selina Meyer?

And as always we remember who we’ve lost and offer suggestions on what to do (living shorter lives), read (Mobley’s terrific piece on the music biz), watch (Nomadland), and listen to (our Spotify playlist).

But first, let me tell you about a bad day my friend Michael had.

Michael Breen had already been in three firefights that day, after one of which he put a guy he cared about on a helicopter. “He was pretty badly shot up,” said Michael, then an Army captain leading a platoon in Iraq. “So you had a day already.”

That’s when someone blew up a bus full of civilians. Five minutes later, Michael was the first one on the bus. In his gentle voice, Michael described, in detail, a version of hell that should not exist. The least of it were the dead children. The worst were those whose bodies had been destroyed but whose brains still worked enough to ask Michael for help he could not give.

“But you're in charge of other people, and you're trying to help the people that you're trying to help. And there's a risk of attack. There's secondary devices that could be around, there's a lot going on. And you have a bunch of soldiers looking to you, Hey, would we do? So in that moment, you can kind of look down at that human being who is literally dying and looking to you. And you're there with that human being surrounded by other dead people, surrounded by all the things you're seeing. And you think, ‘This is awful.’ And then you just do your job. It's almost like all of the humanity that you're experiencing in that moment just kind of gets put behind a glass wall. And you can see that the human part of you on the other side of the wall is really having a hard time with all of this.”

Michael only told me about the bus incident to explain how that glass wall protected him from his own humanity. This wasn’t his worst day in Iraq or the end of that one, which had three more firefights before it was over. He had another year of combat after that day before he shipped home

By then his coping mechanisms had become a way of life for him. “Which is a little like what people are going through now. At some point I just need to get out of crisis mode. Like I need to feel like it's over. And the longer that you go between chances to stop the harder it all gets in terms of recovery, and the more encoded all this stuff, this way of living becomes. You're living in a permanent combat mode,” said Michael. “We're coming up on a year of it. I think COVID is a lot like a tour.”

Remember last March? After the novel coronavirus gladiator-marched from China across Europe before pummeling Italy and New York, we entered a heightened state of alert, bleaching groceries, washing our hands for 20 seconds, and studying the properties of H-VAC systems. The world had become a threat. Then came anti-maskers and Trump saying we should inject bleach and then George Floyd and they burned the Minneapolis police station and then suddenly the whole country was chanting “Black Lives Matter” and then the death toll reached 100,000 and then RBG died and then Trump got COVID-19 and then there was that abusive debate and “Stand down, and stand by” and then the election Would. Not. End. and then Trump incited an insurrection and then congress impeached Trump again but Republicans were like and? and then it got as cold in Austin as it was in Moscow and thousands of people still don’t have water. And now it’s about to be March again.

Our bodies are built to handle stress in short bursts. After a threat passes, hormone levels return to normal, adrenaline and cortisol levels go back down, and your heart rate and blood pressure settle. But chronic stress, much like combat stress, locks the system into a constant battle readiness. Your brain changes as the abnormal normalizes. The amygdala gets bigger, the hippocampus gets smaller, and you become worse at dealing with future stress.

“I think COVID is a lot like a tour.”

“Over time, people are just super adaptable,” explained Michael. “We adapt. But one of the things that happens is we get complacent. At the start, you'd be afraid to go outside without a mask in March. And now all of a sudden, it seems like a stupid inconvenience. You have to either keep scared or keep the people around you scared. And that in itself is exhausting. What you're really doing is right. You're convincing yourself and the people you love that the world outside is fundamentally unsafe. It's a way to get yourself to wear the mask, but it's an exhausting way to look at the world.”

And that’s why we’re exhausted. Maybe we’re also having short-term memory problems, trouble sleeping, nightmares, or exaggerated responses to stress (it’s loud noises for me), or difficulty being present. “The mind drifts, right? It's a defensive mechanism,” explained Michael. “You develop skills in traumatic situations that can turn into challenges later. Compartmentalization can be really, really useful to get through a serious situation. It's almost like watching it happen. I'm terrified. I'm aware that I'm horrified, but it's through a thick glass and then I'm not horrified right now.”

And then you come home, and all the toxins your body has been storing up flood your brain because now it’s safe, which is why I felt like crying after a week when Maslow’s hierarchy of needs was on back order. For Michael, exercise became excruciating, and loud noises pulled him immediately back into combat mode. “I still just sort of know, without really being aware that I know, where I would take cover at any given moment,” said Michael. “My partner calls it my tactical sub-routine that runs in my brain all the time.”

This is how Michael experienced post-traumatic stress, and he’s explained it to me not for sympathy but because he recognizes that his country is on its own combat tour. Life expectancy is falling. So-called “deaths of despair” are rising. “The emerging literature on the impact of the pandemic on mental health… shows high rates of psychological distress and early warning signs of an increase in mental health disorders,” reports The Lancet, a psychiatry journal.

“It's not really useful or particularly human to have a trauma Olympics.”

Michael acknowledged there is a difference between the trauma caused by combat and social distancing, or for that matter whether your power was off for a day or a week. And besides, I’m fine, right? Others had it worse than I did. Why should we complain? You can always rationalize your own suffering by telling yourself that someone else had it worse, but Michael has returned from hell on earth to tell us that chronic stress doesn’t care if battle stations are figurative or literal.

“It's not really useful or particularly human to have a trauma Olympics about who's been through more,” he said. “I don't say that to you to be a nice guy about it.”

This is where I need to admit to you what Michael probably already knows. Last week left me haggard, exhausted, and quick to overreact. Who was I to claim to have suffered when so many others had it so much worse? I kept reciting a litany of my friends’ woes like I was fingering rosary beads. So I reached out to Michael and said people might appreciate having their trauma validated by a combat veteran. But what I really wanted was for him to absolve my shame. If Michael, who had really suffered, could validate mine, then maybe I could forgive myself.

It turns out, Michael knew about the trauma Olympics from first-hand experience, which led him to avoid treatment for a long time.

“What is my experience up against another experience? But you can always do that to yourself,” said Michael. “There were all kinds of things I didn't do because I had friends who'd been horribly wounded. I wasn't ever badly wounded. I had friends who had much worse experiences than I did, so who am I to do X, Y, Z?”

For a decade, he told himself he was fine. This is when I met him. He led a national security organization I belong to. He looked perfect, a soulful, patriotic veteran with an easy smile and a gift for inspiring rhetoric. There were signs, perhaps more obvious in hindsight, that all was not well — his marriage failed, for one, and there was a pained expression he used to deflect. But he seemed fine, and that, as it turned out, was what was keeping him from honestly dealing with his PTSD. It wasn’t that he wasn’t fine. The problem was that he was fine.

“I've come to think of it as this fallacy of being fine.”

“I've come to think of it as this fallacy of being fine,” he said. “I don't want to be fine in my life. I want to live an abundant, joyful, balanced, wonderful life. So what is this? I'm fine. So I'm not going to do anything about it. I mean, that doesn't make any sense.”

Trauma can lead in two directions - stress or growth. In fact, post-traumatic growth is twice as common than post-traumatic stress. You can’t avoid trauma. In fact, everyone has at least five or six in a lifetime. And you can’t, as Hemingway wrote, avoid the pain by shrugging it off. What determines whether your trauma leads to stress or growth is the story you tell. Do you tell yourself a hero story about how you put yourself back together again? Or do you minimize what happened to you and tell yourself that because you were one of the lucky ones that you weren’t broken, too?

Now Michael’s learned how to grow from his trauma, that “the impact isn't all negative, but it's just something you gotta be aware of.” He’s also found a new perspective on his trauma by adopting a couple of shelter cats. One of them, like him, is hyper-sensitized to sound. “If she hears anything, she alerts on it. It's a survival skill. She adrenalizes really easily at sound,” he said with a warm chuckle. “I was like that for a long time, and it was really useful overseas.”

The original treatment protocol for combat stress was PIE, proximity (treat those closest to the combat first), immediacy (treat them right away), and expectancy. That last one meant setting the expectation that the affected soldier would return to the front after he had healed. And though the protocol has evolved over generations, I appreciate the importance of telling the soldiers that the trauma had not ended their utility. They still had something to give, but to do so they had to get back out there. And that’s what Michael eventually chose to do.

“I decided it was like, Oh, I actually deserve to be happy and I'm going to do that. And I don't give a [tinker's damn] what anybody else thinks.”

Michael, who now leads a global human rights organization, spoke to me from the 10-acre quarantine retreat on Orcas Island in Washington state he shares with his fiancé and, when custody allows, his school-age daughter. He was looking across the Straits of Juan de Fuca at the snow-capped Olympic Mountains. “And just as I'm talking to you a great eagle just went by,” he said. “Life is all right.”

After more than a decade of telling himself that he was fine, Michael is all right, too. And if Michael, who went to hell and back to tell us that if suffering is universal then so is healing, has figured out how to be happy, then we can all be stronger in our broken places.

Pandemic Workouts: A Quaranzine

by Elise Hu

Elise Hu, an editor-at-large for NPR and the host of the TED Talks Daily podcast, makes her debut in The Experiment today with a ‘zine — or, if you will, a quaranzine — of pandemic workouts. The last year of the pandemic has been the worst decade ever, but the one thing that unremitting stress has going for it, especially for a working mother like Elise, is the endless opportunities for self-care. And if you think that’s funny, you’re going to love “Pandemic Workouts: A Quaranzine.”

Bidenfeld

by Jack Hughes

Kamala Harris is not the first woman vice president, just the first one in real life. Before her, VEEP’s Selina Meyer rose from playing second fiddle to the presidency. That character, portrayed by Kamala super fan Julia Louis-Dreyfus, is one model for Harris’ future. Another, also played by Louis-Dreyfus, is Elaine Benes. In his latest contribution for The Experiment, Jack Hughes breaks down whether Harris becomes president or the Biden administration ends up being about nothing.

Who we’ve lost

This son-in-law

This newspaperman

How we’re getting through this

Rewatching this TikTok

Having the new jab (h/t Gigi Bradford)

Cooking beef stew with maple and stout

Wearing these to be less likely to catch the plague

What I’m reading

Jonathan Chait: “An Ex-KGB Agent Says Trump Was a Russian Asset Since 1987. Does it Matter?” - Some day this is going to make a great Curtis Sittenfeld novel.

Shvets told Unger that the KGB cultivated Trump as an American leader, and persuaded him to run his ad attacking American alliances. “The ad was assessed by the active measures directorate as one of the most successful KGB operations at that time,” he said, “It was a big thing — to have three major American newspapers publish KGB soundbites.”

Mike Clark-Madison: “The Way We Got Here: On the journey to today’s Austin, Ron Davis helped make the road by walking” - A tender and thoughtful remembrance of a quiet leader. (h/t: Michael King)

It's not all that out of character that even in death, former Travis County Commissioner Ron Davis stayed one step out of the spotlight while other, louder news was being made. The longtime champion of the Eastern Crescent got a lot done that way, in a career stretching back more than 30 years.

Ryan Holiday: “100 Very Short Rules for a Better Life” - Lots of good stuff here.

14. Don’t argue with facts just because you don’t like them.

15. It’s not about routine but about practice.

16. Forget credit. Do the work.

Austin Kleon: “The good enough parent” - This. All of this.

Me, I’m trying to see it as a comedy, or a farce, or maybe just bad improv. Making do with what we have.

We might not be able to be good right now, but we can be good enough.

Mobley: “The Work of Art” - Apparently he writes prose as well as he writes songs.

…artists are just workers like any other. While our works can’t be reduced to their value in the marketplace, we desire and deserve the dignity and comfort that is the right of any worker—any person—in our society. We deserve stable housing, health care, the ability to feed ourselves and our families, rest, happiness.

Dan Sinker: “There’s No Such Thing as a ‘Good’ Parent in a Pandemic” - Reading this hurt my skin from the inside.

What Ted doesn't know is that being a good parent isn’t about flying to sunny Mexico in the midst of a climate disaster and a global pandemic, it’s about teaching your kids compassion, leadership, perseverance, and empathy. It’s about showing them that they live in a world and take part in a society. It’s about trying to explain, however poorly, that their grandparent is sick, why the trip to Disney was canceled, that they can’t go over to their friends house no matter how much you would love that as well. And we do that because we’re trying to be good parents, even though all it does is make us feel like bad ones.

Curtis Sittenfeld: “Rodham: A Novel” - Burned through this in three days. The premise is irresistible: What if Hillary had not married Bill? Read an excerpt here. (h/t: Sonia Van Meter)

“Bill Clinton just called to say he’s running for president and he wants me to tell reporters how great he is.”

“Wait, really?” Maureen said. “Oh, geez. Are you okay?”

“Those weren’t the words he used.”

“I know everyone thought it was his destiny, but it’s wild that he’s actually running. Can he win?”

“It’s not impossible.”

“Do you wish you were married to him?”

I hesitated. “No?”

What I’m watching

I didn’t think I’d like Nomadland even though Ann Hornaday strongly recommended it. There’s something about tales of people who reject mainstream society that make me feel judged, and it had the look of a jeremiad about economic inequality, and those usually come across as pedantic, at least to me.

But this movie was magic. See it.

What I’m listening to

We find the best way to read The Experiment is while our Spotify playlist is on in the background. This week we’re featuring, quite by accident, Los Angeles-based artists.

Chris Pierce, a Los Angeles-based singer-songwriter, dropped a fierce but spare album, American Silence, that recalls ‘60s-era folk. “Sound All the Bells” is a helluva song.

In a similar thematic vein but in a richer musical world is Adrian Younge, also of Los Angeles, whose new album The American Negro combines lush r&b with police sirens. This song, “James Mincey Jr.,” is named after the young man who was killed in a chokehold by a Los Angeles police officer in 1982.

Let’s go out on a happy note, shall we? Sia directed Lavender Diamond’s video for “Open Your Heart,” a boom-clap-clap pean to romantic optimism.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

If your new year’s resolution was to lose weight, try Noom, and you’ll quickly learn how to change your behavior and relationship with food. This app has changed my life. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works.

Headspace is a meditation app. I’ve used it for a couple years and am absolutely shocked at how much it’s taught me about managing my inner life. Try it free for a couple weeks. Don’t worry if you’ve never done it before. They talk you through it.

I now offer personal career coaching sessions through Need Hop.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had.

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.