Regulator, chapter 9

“You will not take my grandchild away,” Grace said in a tone that would haunt her husband until the end of his life.

Gettin’ a little backstory this week with the origin story of one Katy Laughlin. I dare you to read this and not like Frank A. Spring.

by Frank A. Spring

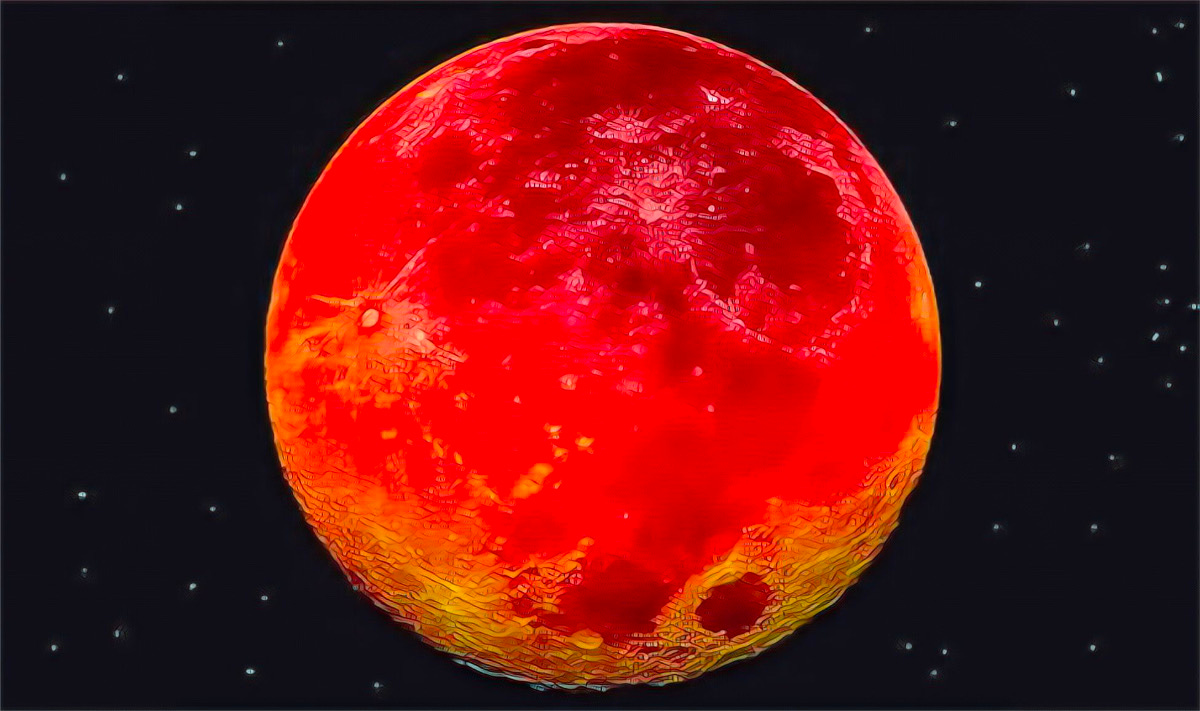

They still called it a Comanche Moon in places where that once had meant something, sometimes everything. By the time Katy Laughlin and Jessamine Halley and their companions robbed a bank in Plainview Oklahoma, it had been almost twenty years since the Quahadi band of the Comanche - their villages burnt, their horses slaughtered, themselves killed young and old by disease and hunger and the US Cavalry - surrendered to reservation.

But in the place that had once been called Comancheria, Kansas to Mexico, East Texas to the Rockies, and especially on the Llano Estacado, that vast sea of plains and bluffs and mesas and canyons, especially there, a moon bright enough so you could see the ground in front of you still made people lock up their livestock, bar their doors, and check that their rifles were close at hand - for all the good that would have done. Old habits, like so many things in Comancheria, died hard.

It was not, as it happened, on a night with a Comanche Moon that Katy Laughlin’s grandmother, Grace Katherine Teeling had been taken. One clear afternoon a small party from the Penatuka Nuu band of the Numunuu tribe - who the Utes had called kɨmantsi, “he who wants to fight me all the time”, and the name stuck - rode up to her family’s homestead not far from San Angelo, Texas, killed her eldest brother outright, looted the place, and made off with her and her brother Philip. Grace did not see what became of her parents and the rest of her family, which was probably just as well.

A certain amount of wrangling attended the disposition of the terrified children when the raiding party returned to its band’s sprawling, mobile village several hours later. The warrior across whose horse Grace had ridden, a tall young man called Mukwooru, presented her to his wife, Lotse, with great satisfaction, and received a round scolding for his trouble; could he not see that this child was just that, a child? That it might be several more seasons before she could bear him a son? If not longer. If not longer. And during this time they’d be stuck with a weak girl who knew nothing, nothing at all, and would have to be fed, clothed and given somewhere to sleep, not to mention taught every little thing and constantly watched to keep her from stealing.

All of which, the outraged lady declared in anticipation of Mukwooru’s objection, she would have been perfectly prepared to do, would have done it gladly, had the girl been ready to bear Mukwooru a child, which any fool could see she was not. They would have been far better off with the boy, who, though equally useless at the moment, might someday add to the family’s herd of horses and generally do them credit.

Mukwooru’s father had named his son after a renowned chief of the Penatuka Nuu, and Mukwooru had always endeavored - sometimes successfully - to carry himself with a touch of the great man’s style and authority. This, combined with his height, made him an imposing figure in any circumstance, and he was perfect hell with lance and bow, on horseback or on foot. But mighty though he was, he had not survived murderous encounters with Texans, Apache, loathsome Tonkaweya, and one memorably outraged bull bison that simply refused to be killed, without learning which battles can be won and aren’t worth fighting at all.

And so the chastened Mukwooru dragged his miserable captive through the village to the hut of Dohate, a Kiowa man who had thrown in his lot with the Penatuka Nuu years before and who, riding now as one of their warriors, had claimed Philip. The wretched settler children squealed at the sight of each other and cowered together as the men, oblivious, set about negotiation.

Mukwooru had had some vague notion of selling Dohate on the idea of the girl as a good deal in the long-term; Dohate had daughters to instruct and watch her, and she’d be ready to bear children soon enough, while he, Mukwooru, was on reflection more interested in expanding his herd, and thus could use a warrior son sooner rather than later while he continued to try for a child with Lotse.

This line of argument fell apart almost immediately, Dohate not having been born yesterday. The Kiowa man already had several daughters - more than he might have cared for, frankly - and he certainly was not in the market for another girl, while his wife had never had much difficulty conceiving and carrying a child (a rare and valued trait amongst the Numunuu, who spent so much time in the saddle that it affected the birth rate of the whole tribe, hence their willingness to adopt members of other tribes and to take captives who could become warriors or bear more children).

Furthermore, Dohate went on, his own boy - a pre-teen lad who watched the whole scene stoically bar an occasional disgusted look at Philip - needed a brother.

“He is a good boy but he gets lazy and complacent,” Dohate said. “And a boy never fights so hard as he does against his own brothers. Mine left me many scars, each a lesson and a blessing in its way.”

Mukwooru argued the toss for form’s sake, and then, desperate, offered to sweeten the pot with a horse or two, but Dohate was resolute, and Mukwooru soon grew discouraged. Moved by the younger man’s distress, Dohate reached up to place a hand on his shoulder, assuring him that he and Lotse would certainly have their own child soon, a strong and worthy son no doubt, and promising that he, Dohate, would have his daughters help Lotse instruct the White girl and keep her in line.

Lotse was not best pleased to see her husband return still in possession of the pathetic White girl, but the set of his shoulders told her that the time for argument was over and she did not vigorously protest when Mukwooru announced that he and Dohate had talked it over and concluded that it was best if things remained as they stood. If the girl proved more trouble than she was worth, they might be able to ransom her, Mukwooru reasoned, or they could get rid of her more expeditiously, though neither of the couple seemed very enthusiastic about that idea.

Thus did Grace Teeling come to live with the Penatuka Nuu.

Grace’s days on the Teeling farmstead would not have been easy - survival never assured, comfort guaranteed only to be absent - but her life with the Penatuka was more difficult than she could have imagined; days of hard, grim labor cleaning buffalo skins with a stone knife, tending a truly shocking number of animals, and endlessly bearing one burden or another.

That Lotse worked just as hard as she did offered no comfort, especially since the lady, while not actually cruel to Grace, treated her with the same hardness she would show a dog that was unwilling to learn or do its duty. There were long periods when it seemed to Grace that she must die of exhaustion or sheer despair (she would not have been the first, in those circumstances), particularly as Dohate and Mukwooru had agreed it was for the best if she and Philip were kept away from each other.

Grace would see her brother from afar, every now and again, riding out with Dohate or running with the other boys, and she watched him change over time; darkened by the sun, and moving differently, his sinewy body noticeably bowlegged from all that time in the saddle. She was not surprised the first time she heard him laugh.

Faced with a stark choice between adaptation and death from mere misery, Grace did the only thing she could think of - worked harder, and applied herself to learning the language of the people who were both her captors and family. This bought her almost no leniency from Lotse, but as Grace became increasingly able to take on her chores without instruction or close vigilance, Lotse seemed to get used to her.

The turning point in their relationship occurred when Lotse delivered herself of a baby boy. Mukwooru was endlessly delighted, as if he did not know that the baby was colicky and his wife weakened almost to death by what had been a prolonged and difficult delivery. The women of the band did their considerable part to see mother and child through this dangerous period, but Grace was the most constant comfort, partly out of motivated self-interest (who knew what her situation might become if Lotse died) and partly because she had conceived an unlikely affection for the little yowling bundle of fury. Lotse did not treat the White girl with warmth thereafter, but she softened, and Grace found with gratitude that her own portions at meals increased. Mukwooru meanwhile had a smile for everyone, decreeing the boy’s constant bellowing to be a sign of strength and spirit with such oblivious satisfaction that Grace would hardly have blamed Lotse if she’d impaled him where he stood.

If Grace’s life had become more comfortable, it was only in that the profound and constant discomforts of her early days had been reduced. Dohate’s daughters hardly ever came around anymore to instruct her on her duty, and it had been some time since they had kicked or cuffed her, much less flayed her with their riding quirt; she was no longer constantly, achingly hungry, though she would gladly have eaten at any time; and she was now reasonably confident that Mukwooru wasn’t simply going to kill her outright.

She grew accustomed to the rhythms of life in the village, came to have expectations for what she would do and what would happen to her, and had those expectations met, confirmed, reinforced. Those rhythms guided and numbered her days, and despite her best efforts, Grace’s old life receded, fading into stories she’d heard years ago about things that had happened to someone else. Life with the Penatuka came to be the natural order of things. When Lotse told her it was time for her to bear Mukwooru a child, Grace steeled herself; she did not and could not accept, for she had no meaningful choice in the matter, but she had seen and heard what the couple did in the tipi at night and had prepared herself to do endure it.

Spring. Flowers in bloom, the village packed up and moved out of the canyons where they had wintered, back onto the plains of which they were master, the men riding out more and returning with meat and plunder and the occasional empty saddle. Then months of heat so crushing that by common consent the Penatuka abandoned their summer lodges and moved farther north than they had in years, into the territory of the Yaparʉhka, the northernmost of the Numunuu, who greeted them hospitably, there being abundant game that season, and together they raided as far down as Mexico, the warriors setting out wearing buffalo intestines coiled round their shoulders like scarves to gnaw on so they would not have to stop to eat. Cold wind later, a harsh winter coming maybe, and the Penatuka returned to their winter camp in the southern parts of the Llano. The smoky warmth inside the tipis, and the vicious, ceaseless wind without, endless cured buffalo meat and everyone confined, hemmed in, grumbling. Then the flowers again, warm breezes and fresh meat and boys celebrated for making their medicine with their first buffalo kill, becoming warriors, marrying Dohate’s daughters. And thus and thus.

Flowers bloomed new on the plains again when Mukwooru led Grace along the river that ran through the winter camp, itself now a hive of activity as the Penatuka prepared to once again leave the sanctuary of the canyons and return to the broad grasslands under the open sky.

Where the river merged with another, at the mouth of the canyon, they found a small encampment of comancheros. Rough men, they were, many with dirt still on their faces and blood on their clothes, and even the neatest among them, those hardy enough to wash in the frigid water, wore their years of tense deals under drawn guns and cheerless camps under grim skies and bad food and killing like pennants. Some things show in the eyes.

As soon as Grace saw them she knew. Her stomach turned and her knees locked and for a moment the world tilted on its axis. She did not want this, feared it. But this decision had already been made, and Mukwooru, seeing her quail, told her as much, simply but not unkindly, and they walked on to meet the comancheros’ captain. She did not think to ask to speak to her brother one last time.

This was the first comanchero deputation to the Penatuka of the season. Spring visits were chancy; the comancheros might find the band had had a gentle winter, and not in need of much, and so the trades would be few and poor, or that they had had a hard winter and so had little left to trade, with the same result. Or a gentle winter might have meant they could raid far, and so would have spoils to trade, and a hard winter might mean desperation, and treasures held back against calamity would be traded now for a song. Or the band might already be gone, and a journey of several hard days would become one of several weeks, or end in total failure. Not necessarily bad business, these spring visits, but chancy, chancy.

This one had been good. The Penatuka were, as a rule, good trading partners; they raided far and wide, and hunted likewise, and so had hides and property to trade, and need for guns and ammunition, metal tools, and the like. Just as importantly, the band’s elder council liked what they were used to, and they were used to this party of comancheros, who had won the right to deal with the Penatuka by a policy of scrupulous honesty toward the band (a rare state of affairs) and implacable, murderous hostility toward their own competition (much more common). The result was a steady, profitable enterprise for these comancheros, allowing them to focus on the mercantile side of their trade and rarely if ever stoop to the bounty-hunting or banditry by which so many of their contemporaries tied both ends of the month together. As long as they could avoid dying of thirst or being swept off the Llano by a blizzard or getting slaughtered by their competition or outlaws or Apaches or all three working in concert (it was not unknown), life as a comanchero to the Penatuka Nuu was as good a gig as they could ask, and better than most of them felt they had a right to expect.

It was not surprising, therefore, that their captain greeted Mukwooru with deference, and bowed civilly to Grace. He looked at her intently, reviewing her against a memorized description.

“You are Grace Teeling?”

She did not know how to answer, turned to Mukwooru, who nodded impatiently. She lowered her eyes and nodded, too.

There followed a final round of negotiation, conducted in Numu and Spanish and the occasional burst of hands signs that served as common language for many of the Plains peoples, during which Grace became acutely aware of how tense this party of heavily armed men was, how anxious they were to both please Mukwooru and also not to seem weak or foolish to him, how just plain afraid of him they were. In the end the comancheros bound some metal hatchets together and added them to a pile of goods on a sled yoked to a horse. Mukwooru handed the comanchero captain a small sack, then deliberately appraised the sled horse from hoof to teeth while the comancheros looked nervously on. Eventually he nodded slightly at the comanchero captain and led the horse and sled back toward the camp.

Thus did Grace Teeling come to leave the Penatuka Nuu.

The why of it all was evident enough, and Grace had more than enough time to contemplate it as the comancheros made their gradual progress across the plains. She had not borne Mukwooru a child, that was the short of it; the long of it was that it had been a hard and unlucky season for the family, Mukwooru having a succession of horses shot out from under him, and another dead bearing a foal, and another from some kind of poison, and the raids had been hard and spoils sparse for him, and so a new horse and some goods for use and trade would come in very handy for Mukwooru just now while he got his medicine back in order.

She’d obviously been ransomed. It was common enough - a number of the Penatuka’s captives had been sold back while Grace had been with them; sometimes that was the entire purpose of a raid, and the warriors would hang around near where they had struck long enough for family and friends to arrange a payoff in a matter of days. More often the interval was weeks or months, sometimes longer. There were men who made a tidy parcel as ransom agents, gathering information from distraught relatives about the people who hadn’t been found amongst the slain, mangled, and charred, and working with the comancheros to figure out if the survivors were alive, and where, and if there was a deal to be made. Grace asked the comanchero captain to tell her who had bought her; he affected not to understand, but it was absurd to pretend that he did not know the Numu words for exchange and she told him so with such indignation that he looked abashed, gently tapped his ear to show that he had simply misheard, and told her that she’d been sold back to “relatives.” No more could he, or would he, say on that.

She learned more from the ransom agent to whom she was given for the final part of her journey. Her maternal aunt had married a doctor in Austin, and the family had made it known to anyone who’d listen that they’d ransom back both Teelings. Only Grace had been on offer. She would be delivered to them.

The comancheros and the ransom agent were neither cruel nor kind to her; they gave her what comforts they could offer and they did not bind her, but they watched her carefully and all the time. She would not have been the first ransomed captive to run back to the Numunuu. But Grace had no intention of running; it was a long and hard way back and they’d only send her away again, this time beaten, and bound with leather thongs. No. Whatever future she had lay ahead.

One night the ransom agent handed her a frock. “Wear this tomorrow,” he said in English. The next morning they came to a point where the houses near the road were more numerous and closer together and the ransom agent paid off his outriders, who tipped their hats and disappeared, and she was wearing that frock when they rode into Austin and to the home of Dr. Jonah and Cynthia Young.

Tearful embraces from an aunt she would barely have recognized when she was taken and who could have been just about anyone now, the doctor looking her over with distant curiosity, her English grinding to life. The ransom agent offered the contents of the small sack Mukwooru had handed over to the comancheros as proof of Grace’s identity - trinkets taken from the Teeling homestead, a broach, a belt buckle, an inscribed plate - but Cynthia Young had been persuaded from the first and her husband paid off the agent and bundled him out the door as quickly as civility would allow.

Installed in an upstairs room of the Young’s genteel house, given clothes and brushes and all manner of objects, and gently instructed to make herself at home, Grace was left alone and idle for the first time in…years? Ever? Taking in her immediate surroundings did not require much time, and she was left with a new and novel reality: she had no idea what to do with herself.

She was not the only one. Grace’s aunt would gently offer her a variety of options for what they might do together, to which Grace would remain silent, not only unclear on what ‘canning’ was, or why anyone would simply walk around without purpose, but on what basis she was supposed to make a choice between them or any of Cynthia’s other notions of how to pass the time.

Cynthia Young, however, had raised four children, three to adulthood, and quickly understood that she would simply have to instruct Grace on what they would be doing now and how to do it. And so Grace began to learn to can okra from the garden and discover what virtue there might be in walking aimlessly around the Young’s leafy neighborhood. She did not particularly enjoy any of it, but it was at least something to do, and better than being idle and talking, which her aunt seemed to do a great deal of with the women who would come to visit. Grace sat in silence during these episodes, partly because her English was still returning and principally because she could not think of anything she had to say to any of these people and did not much care to try. Both their manner and their matter seemed to her offensively trivial.

This slow acclimatization under the Youngs’ eye might have continued for years, and who knows how far it might have gone, had Grace not started vomiting mornings, initially without apparent cause and then, after a brisk examination by Dr. Young, for a cause that was all too apparent.

Grace was unperturbed, which seemed to perturb the distressed Youngs even more. This was not the first time she had become pregnant by Mukwooru, but she had never come close to term, and assumed this would likely end the same way. The Youngs shared no such confidence and were obviously carrying on a lengthy conversation about What Was To Be Done, an exchange which stopped every time Grace walked into a room and seemed to reach a pitch of intensity in the couple’s private rooms late at night. After a few days the running conversation abruptly ceased, replaced by an even-more pointed silence.

She was to be married. Cynthia explained this to her after a day’s worth of tense silence in the house, with Jonah sternly reinforcing such points of hers as he felt important. Grace’s future husband would appear tomorrow and take her walking at stated times for a week, after which they would be wed and she would go to live with him. She would, Cynthia was sure, be happy with him.

Grace was not at all sure of this and knew that her aunt wasn’t, either, an impression strongly reinforced when Robert Laughlin, her betrothed, appeared the next day. He was older than Grace had expected, a tense, fair-haired little man who paid her only the barest attention during their public walks and even less during their brief periods in private. The Youngs had been anxious to get rid of her and this man clearly stood to gain by taking her off their hands, though Grace could not tell exactly how just yet. This period of walking around together was obviously a performance meant to persuade someone that this arrangement was something other than what it was.

The ceremony was private and perfunctory, accompanied by no celebration to mark the occasion. Grace Teeling became Grace Laughlin as far as the State of Texas was concerned, and moved into Laughlin’s small suite of rooms, where they slept in the same bed but Laughlin acknowledged her as much as he would if she had been a down-stuffed pillow. During the day she feared she might actually die of boredom, and was greatly (and to her surprise) relieved by the visits of her aunt, whose ostensible purpose was to instruct Grace on how to keep house (an unnecessary task given that all such duties were handled by Laughlin’s landlady) but who seemed primarily interested in keeping an eye on her niece’s welfare.

The nature of the Youngs’ bargain with Laughlin became clear almost immediately. Laughlin was a surgeon’s assistant who, through ill-luck and ill-management, had failed to build his own practice and was now old for his position. Directly after his marriage he went to work with Dr. Young, and shortly thereafter he and Grace moved out of the suite of rented rooms and into a large home, which in the years that followed Grace managed only to the extent that she was inclined and often in a manner that got her crosswise with the domestic staff that Laughlin had hired without her consultation. Laughlin handled Grace as if she were a piece of expensive furniture, respectfully delicate whenever he was obliged to interact with her but otherwise taking no notice of her at all.

He seemed utterly nonplussed when Grace gave birth to a baby girl, and was not perturbed or even especially interested when his putative daughter came out in jet-black hair and was obviously tall as soon as she could stand. She bore him no resemblance at all, but had both of her parents cared to, they might by sheer force of will have persuaded their small corner of Austin to acquiesce to the fiction that Little Cynthia, as the family called her, was Laughlin’s.

Neither parent did, of course. For his part, Laughlin’s end of the bargain went no further than marrying Grace quickly enough for that fiction to even be possible, and as he’d gotten what he wanted - the title “Doctor” prepended to his name effectively by common consent; a burgeoning practice and with it money to spend on his true passion, opium; the trappings of a respectable, established life - he considered his part of the contract effectively fulfilled.

Grace, meanwhile, did not and would never have time for what her aunt referred to as “society”, such as it was. She attended church with her husband because it was represented to her that this was a necessary duty, during which she paid no attention at all, declining to join prayers or to sing hymns. She absolutely refused invitations to join various ladies’ organizations, mostly run through the church; she did not call on other ladies, and casually turned away visitors because they did not interest her. Her behavior was a source of constant comment in the Youngs’ and Laughlins’ community, a world in which differences of opinion between people, especially ladies, could either be resolved by finding and celebrating common interests or could deepen into shockingly venomous sub-rosa feuds (in either case the whole affair papered-over with the saccharine bullshit that even then passed for manners in the American South). Either approach was considered fine, but to not care at all was as unthinkable as it was unforgivable.

Frustration with the Laughlins’ - especially Grace’s - refusal to even attempt to fit in was exacerbated by the fact that there was no apparent way to punish them for it. A transgressive family could generally be brought around, or driven out, by a commercial and social boycott, but the community was not spoiled for choice with medicos and might well be stuck with Dr. Young’s successor, while the Laughlins had chosen their social embargo for themselves and seemed no worse for it.

Little Cynthia proved the answer to this problem, and some of the more poisonous members of the community put it about that whatever anyone said, the child was obviously half Comanche and therefore dangerous as a wildcat. Aunt Cynthia, as her niece and grand-niece called her, spent the rest of her life fighting a desperate rearguard action against this malice, and early in the conflict Jonah Young had a stern word with Laughlin to the effect that if he and Grace would not take active measures against this slander they could at least have another child for appearance’s sake, allowing further that he did not envision leaving his practice to a man who was publicly scorned in this way.

“We should have a child,” Laughlin said to Grace the next night.

She considered.

“I would like always to have a horse,” she said. And so the deal was struck.

The arrival of Robert Junior (the Laughlins were not long on originality) did not have the intended effect; his growth into the compact, light-haired image of his father only reinforced the impossibility of Robert Senior as progenitor of Little Cynthia. It did, however, have the unexpected consequence of rousing Robert Senior from his torpor; he spent less time with his opium and more building his part of the medical practice and raising the boy. This was good news for his son and for the family’s fortunes generally, but did nothing to protect Little Cynthia from the ostracism and public insult to which she was subjected first by venomous neighbors and then by their children.

“This should not bother you,” Grace told her distraught daughter. “They are fools, and you should not trouble yourself to be liked by fools.”

Grace was not neglectful, teaching her daughter such things as she deemed useful, and both of them found great joy in riding horses, at which they were superb. It was Aunt Cynthia who undertook the totality of her namesake’s social education, with far greater success than she had enjoyed with Grace. The result, perversely, was that Little Cynthia was fully aware of and anxious to participate in the customs of a society that refused to admit her, a banishment that went from partial to complete when, just as Little Cynthia should have been introduced to the world as a young woman, Aunt Cynthia rather thoughtlessly died.

Is it any wonder that Cynthia Laughlin - now a towering presence with black hair and watchful eyes, no longer Little Cynthia in moniker or fact - should have become, in her late aunt’s words, a little unpredictable? That she should have whipsawed between desperate, plaintiff campaigns to appeal to her family’s affections and squalls of such unrestrained rage that both Grace and Robert began to wonder if they were safe around her?

Before these storms Grace felt powerless; resigned to a life of endurance, she could not - or would not - impart to her daughter the same impassive distance. Robert Senior generally pretended it was not happening, except to ensure that his son was so shielded from Cynthia’s unpredictability that despite living in the same house they were effectively raised in different families.

And for that matter, is it any wonder that in time Cynthia should have engaged in an illicit liaison with a man who openly admired her? Who treated her kindly? They met while she was out riding.

She had reined up under a tree after a particularly exhilarating series of jumps, and he had trotted up. Seeing her unease at being approached by a strange horseman, he’d put his hands up, then dismounted some distance away and walked slowly toward her until he was close enough to speak.

“I just wanted to say,” he’d stammered out, “I just wanted to say that you are the best rider I’ve ever seen. And the loveliest.”

They had ridden together several times after that. He was not in town for long, a few weeks at most, then he must be back out on the road, but he would return, he said, he would return in a few months and when next he left she could leave with him.

It is possible that he meant this, every word of it, and that he failed to return because he lost his life upon the road; it is possible that he did not. Either way, Cynthia never saw him again, and soon enough she began to unaccountably lose her taste for food she has previously enjoyed, and not long after her abdomen began to ever-so-slightly harden.

Robert Laughlin, by this time the community’s only doctor, set about handling this the way Dr. Young had, but found no takers; Robert Junior had just gone east to attend medical college, and it was widely known that he would inherit from his father, and so Robert Senior had no practice to bargain away and no other dowry sufficient to the occasion.

After a period of frantic - and largely inept - searching and bargaining, Laughlin told Grace one night that they would send Cynthia away to a place where she could carry and birth the child in peace and secrecy, and then the infant could be taken in by the church or childless parents or wherever such children went.

“You will not take my grandchild away,” Grace said in a tone that would haunt her husband until the end of his life.

And so the Laughlin household grew by one, and such neighbors as cared to shared increasingly implausible theories about the child’s parentage while vowing in the same breath to pray for the poor little creature, indeed the whole family, bless them.

Cynthia, with the Laughlins’ usual imagination in the naming of children, called her daughter Katherine, Grace’s middle name. If they had hoped that the obligations and joys of motherhood might have steadied Cynthia - and Robert, at least, had been counting on that as the only benefit to the entire sorry situation - then the Laughlins were sorely disappointed. Returning from errands one day Grace heard the infant crying lustily and went upstairs to relieve her daughter, only to find little Katherine filthy, hungry, and alone, who knew for how long. Cynthia, confronted when she returned some time later dusty and smelling faintly of leather and horse, was disinterested.

“She’s always crying,” Cynthia said with a wave of her hand. When Grace suggested that either Cynthia must look after the child properly or they should take on help to do so, however, Cynthia grew agitated and plucked Katherine away.

“Katy doesn’t need a stranger,” said Cynthia with heat and pointedness that suggested that Grace had been treasonous to suggest it, or, worse, might fall into that category herself. “She needs her mother.”

Katy had few memories of her childhood, and those she had always featured her grandmother in some way. Grace was a near-constant presence in Katy’s early life, caring for and instructing her when her mother was not able or inclined to (much of the time), and always nearby during the periodic fits in which Cynthia would spontaneously assert her maternal rights and all but sequester herself with her daughter.

“You can go now,” Cynthia said to Grace one day as she blew into the room and swept Katy up from where she was seated on the floor, interrupting story time and startling the toddler into a wail.

“I do not mind. Let me finish the story,” said Grace. “It is her favorite.” and it was, because if Grace had learned anything during her time with the Penatuka it was how to get the voice of Coyote, the merry trickster, just right.

Cynthia turned to her, her cooing smile fading and the fire kindling in her eyes.

“She is my daughter,” Cynthia spat, and followed the proclamation with a torrent of jumbled words, each angrier than the last, her voice rising to be heard over Katy’s sobs. “She needs me,” she said, reaching her peroration, “and you need to-“

“I will stay,” said Grace in the same tone with which she had informed her husband that he would not discard her grandchild. And that was the end of it.

When she was old enough, Katy began to spend more time away from the Laughlin house. Grace, in an outburst of sociability that stunned all who knew her, ferreted out nearby families with children Katy’s age and arranged for her to have friends, and it must be said that while their corner of Texas certainly featured neighbors who happily gossiped about the Laughlins’ little savage bastard, it was also not short on people who considered such discourse cruel, unchristian, damned nonsense, or all three. Such people found little Katy a cheerful delight and her grandmother perfectly pleasant if a bit distant, not to say odd.

The only point of absolute agreement between Grace and Cynthia was on riding, and they resolved to share this joy with Katy. Grace had come upon Robert Junior, who by this time had inherited his father’s prosperous practice, one morning while he was doing accounts and informed him that they would be purchasing an appropriate mount for Katy.

“And there will be others soon,” she said. “Your niece is growing fast and will outgrow this pony before too long. I will find the right animals.”

Her son did not hesitate.

“Will this be enough,” he asked, withdrawing a stack of bills from his desk, “or will I stop by the bank?”

They were a different family when they rode together, Cynthia most of all. She was funny, light; at home, any suggestion of fault on her part could send her into a towering rage or a spiral of self-flagellation, but on horseback she chided herself as easily as she praised her daughter. Katy learned, as her grandmother had, to save any important conversations that needed to be had with Cynthia for the ride, broaching them delicately so as not to chase the magic away.

Grace’s death, of course, was the end. She had sickened quickly, and her passing left her daughter inconsolable to the point of paralysis. Robert Junior and Katy, themselves grief-stricken, were thrust together, and to their mutual surprise got on rather well. Robert, who had taken his father’s example and kept his interactions with the female members of his family brisk and practical, found that he actually quite liked his niece, who was energetic, curious, and, to his considerable relief, almost entirely self-sufficient. She came to him only when she needed money or an adult’s explicit approval for something, and he treated her like a dinner guest who he’d unexpectedly discovered was in fact quite interesting.

How their strange, if companionable, relationship would have held up under the rigors of Katy’s imminent adolescence is not clear; it might well have buckled and folded on its own, but it was not given even that chance because after a considerable period Cynthia roused herself from her mourning torpor and utterly swept it away. She demanded to know how they could be so indifferent to Grace’s death - in fact both had spent many a tearful night - and furiously accused them of not loving her mother at all. This generally led to lengthy remarks about how they could not understand her grief, or words on a similar theme, delivered in either a piercing shout or a rasping sob, as the mood took her.

The response from both brother and daughter was to withdraw - from her, from the house, from each other. Katy spent her time wherever would have her - the school in which Grace had enrolled her, with her few friends, even church, and as much as possible on horseback. She would often face lengthy and fraught interrogations from her mother upon her return, featuring accusations of disloyalty and misbehavior. So she tried a period of appeasement, remaining at home with Cynthia, but she found the idleness stultifying and her mother’s whipsawing moods exhausting. The interrogations were better.

Robert, for his part, redoubled his existing efforts to secure himself a bride. For an apparently amiable, successful, and tolerably good-looking doctor, his efforts were remarkably unsuccessful, for it was widely known in the community that marrying Doctor Laughlin would mean living with That Woman, as well as acting as surrogate mother to young Katy, and no young woman would do it if she had a better option. He had looked outside their community, as well, but courtship with any woman he thought suitable must inevitably involve the lady visiting his home. Cynthia’s approach to such occasions involved antics ranging from naked insult to hurled decanters.

The young doctor had a number of options for dealing with the situation, and chose a common pairing: resentment and heavy drinking, mixed equally. Whiskey made him inclined to fight, while Cynthia needed no encouragement beyond her own boiling blood, not that she was averse to using a little whiskey as an accelerant. The Laughlin house became a battlefield.

Either of them could have left - they had more than the means to set up another modest household - but, even as the years passed and the air in the house curdled and turned rank with bitterness and spite, neither would decamp, remaining to fight it out for reasons Katy couldn’t imagine. And so one day, it was Katy who left.

She would not have described it as planned, per se. If it had been a thoroughly premeditated flight, she told herself, she would have brought spare clothes. A toothbrush. That sort of thing. She had been out riding and had just, well, kept going, suddenly unable to bear the thought of going back. That story would satisfy any number of curious people later, and largely satisfied her. Of course, it did not explain how the bankroll her uncle kept in his desk drawer came to be in her pocket, but she did not mention that detail to other people and preferred not to think of it herself.

That she passed unmolested through those first few days marked her as the first woman in her family to have any luck at all to speak of. She had no idea if her mother and uncle would send anyone after her but she rode hard. In towns, she’d rest her horse at a hostler while she sussed out whether there was a boarding house in which she was reasonably confident nothing sinister would happen to her. Early on this meant hitching her horse to a tree and sleeping on the ground, and rising stiff, bleary, and shivering with the dawn. She bought blankets in the next town.

The modest bankroll had been all but exhausted and she was on the point of selling her horse when she pitched up in a little town in Kansas, where she quietly asked the landlady of her rooming house if anyone in town had any work going. The landlady suggested she try the grocer.

“Or The Gem,” she said. “Some people might have objections.” She sniffed. “I don’t.”

The grocer having turned her away out of hand, Katy Laughlin presented herself at backdoor of The Gem saloon, thinking this better than strolling boldly through the front door, and asked to speak to the proprietor. A grim-faced man appeared and looked at her with such evident displeasure that she almost apologized and ran, but mustered her courage instead and asked about work.

He looked the tall, dark-eyed girl in front of him up and down.

“Well, normally I’d say we’re all full up on doxies,” he said. “But maybe…”

“Oh, I didn’t mean that,” Katy said hurriedly. “I meant…sweeping up. Dishes. I’d be a good cleaning girl.”

“Already got one of those.”

The extreme disappointment on her face did not move the man’s heart, but it did change his mind. The girl was clearly approaching desperation; given time, could she be upgraded to a different, more profitable role in his enterprise? She almost certainly could.

“Well, now,” he said as she thanked him and turned away, “wait just a minute.”

And so Katy Laughlin started sweeping floors and washing up and generally tending to the appearance of the Gem Saloon, duties she shared with a small young woman with a tear-drop shaped scar on her forehead who was civil to her but otherwise ignored her entirely.

Katy had not been on the job long before she had learned how to deferentially redirect propositions and understand how much manhandling she was expected to endure, which was a lot. Her compatriot with the tear-shaped scar proved more willing to swat away hands and kick shins, a boldness that Katy wished she shared and which was more often than not rewarded with an impressed and appalling chuckle.

Until the day it wasn’t.

Katy was returning from the kitchen to the open front room when she saw the other girl slap away the hand of a sandy-haired young man who if Katy had had her way would have been tossed into the street three drinks previously.

“Don’t you slap me you little bitch,” he hissed at her, and with surprising and almost certainly practiced dexterity he reached up, grabbed a handful of the girl’s hair at the roots, and slammed her face-first into the table and held her there.

“Slap me now,” he mocked as she squirmed. “Go on, slap me again.”

Katy saw the proprietor looking on with disdain; clearly, his plan of action was to do nothing at all. No one else seemed perturbed; a few seemed amused. The man with sandy-hair looked up and grinned.

“Think she’ll learn anything?” He said to his appreciative audience, and at that moment the girl produced a short knife and slit the man’s underarm from wrist to elbow.

Katy would not have believed it possible for a man - for anything - to bleed so much, so fast. Men recoiled from shock, or to avoid the spray, exchanging looks of horror.

The girl did not waste an instant. Before the sandy-haired figure hit the floor howling she was out the front door. Katy looked on the scene a moment longer - the aghast proprietor, the stupefied patrons, the man dying on the floor - then scooped up a handful of bills and a whiskey bottle from the nearest table and slipped out the back into the afternoon.

Katy was afraid the girl’s head start, narrow though it was, would be enough to give her the slip, but the sight of her quarry charging out of town on what was obviously the first horse she could steal put those fears to rest. The animal was a sorry, broken-down paint; Katy and her dark palomino could give them a mile or more without difficulty.

Even so, she burst through the hostler’s door at a dead sprint, exhorted and berated the astonished man into retrieving and saddling a horse faster than he ever had before, and she was out at a full gallop.

The light was only just beginning to fail when Katy finally saw the girl with the tear-drop scar. She’d changed her course, and a slower rider might have lost her, but there she was in the distance, riding that sorry-ass paint for all it was worth.

It was not long before she was in shouting distance, and her first hail had the opposite of the desired effect; the girl made a whip of the reigns and stirred her failing mount to greater speed. Katy closed the distance.

“It’s alright! I’m a friend!” she called, although what right she had to name herself so, she didn’t know.

The pursuit continued until Katy was close enough to see the paint’s rolling eyes and hear its labored breathing as clearly as her own.

“Please stop,” she said, barely needing to yell at all, “before you kill that horse.”

The girl with the tear-drop scar reigned in and turned toward Katy, coiled and watchful. Even though Katy knew she carried only a small knife - if she even still had that - there was something feral and dangerous about her, as if she might suddenly spring from the saddle and tear at Katy with teeth and claws.

“What do you want?” The small, tense figure asked.

“Thought you could do with this,” Katy said, and produced the bottle of whiskey.

The other looked at her for a long moment, then laughed a crowing laugh.

“Give it here,” she said, riding over, and Katy obliged.

When they’d each had a pull - Katy’s second drink of whiskey, ever - the girl with the scar took a deep breath.

“Alright,” she said. “Now what do you want?”

Katy, to her surprise, had no idea how to answer. “Do you think that man’s dead?” She asked.

“Yes,” said the other.

“Good.”

The horses breathing, the breeze in the grass.

“Are they after me?”

“Not when I rode out,” answered Katy. “Think they will be?”

“Depends on whether anyone really liked that sonofabitch,” the other answered. “Or anyone cares much about this horse.”

“Hate to imagine the kind of man who would.” Katy looked at the darkening sky. “It’ll be hard enough to find us here right quick.”

The girl with the scar surveyed Katy and pronounced judgment.

“Wanna ride on a ways?”

Katy smiled.

“Where we headed?”

“Wherever we goddamn please.”

And so Katy Laughlin met Jessamine Halley. They’d been together since, and were in fact together now, literally together, sitting companionably on a sofa on the balcony of a saloon very like The Gem, drinking whiskey, laughing, making plans both small and grand until Jessamine fell silent, and then began to snore very gently on Katy’s shoulder. From the bar room below Katy could hear the occasional clink of glasses and whoop of triumph as their companions spent the first spoils of the Plainview job. Violet had disappeared with Davy O’Connell, as usual. Fine. Katy was happy in the quiet night air, the sweet spice of the house’s best whiskey on her tongue. She looked at Jessamine, snoring contentedly, took a draw on her cigar, and sent a long plume of smoke streaming into the light of a Comanche Moon.

Subscribe to The Experiment to keep up with future chapters of Regulator. Check out Frank Spring’s previous contributions to The Experiment which include “Neither Gone Nor Forgotten,” “Oh, DaveBro,” and “In Praise of Gold Leaf.” For legal reasons, I want to make clear that Frank Spring owns the rights to Regulator, free and clear. Follow him on Twitter at @frankspring.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback this June!