Charlie Antrim comes back into the story to get his mission from James McParland, who some called America’s greatest detective. Here he’s heading up Pinkerton’s Denver office and wants Charlie to see about some people who’ve been robbing trains.

by Frank Spring

“The posse found the other girl miles away, sitting under a tree, shivering, not speaking. They all thought…you’ll know what they thought. No one batted an eye when her ‘father’ said he needed to carry her straight home, and off they went. Got clean away without firing a shot.”

Charlie Antrim sat back in his chair, trying to think if he’d ever heard the like, and as he did his back gave a twinge and he groaned. Anyone, he thought, any fool could look at a map and think the United States of America is a big country, but you couldn’t really know, couldn’t understand the awful truth of it until you’d ridden laterally across Kansas. The train was as comfortable as it could be - the Pinkertons counted few friends better than the railway lines, and agents were always well-tended - but years of cowboying and contending with the Tim Mastersons of the world had taken a toll on Charlie, and after a long journey his body was a mass of aches.

Nor had there been time to stretch out for a bit or perhaps seek a medicinal dram of whiskey when he arrived in Denver; his orders were to report directly to the Pinkerton Headquarters and the regional superintendent knew what train he was on, which left him with no time to indulge in what the late Collum Geary would have called a cheeky one, more’s the pity.

Making his way out of Union Station, Charlie was struck by the contradiction between the station, which was obviously getting too small for its traffic, and the large number of idle, able-bodied men gathered in knots or lounging singly outside. Denver’s abundant commerce apparently was not keeping its citizens in work.

His reflections were interrupted by the sudden presence of a small, more or less filthy boy, who presented himself in Charlie’s path, tipped the greasiest cap he’d ever seen, and offered to guide Charlie and shoulder his bag no matter how far he had to go.

“Will you run me up to Platte Street?”

Several nearby conversations stopped. The boy seemed unperturbed.

“Rankin’s Depot, is it?” he said, and something in the lad’s eye made Charlie nod in agreement. “Right away, sir,” the boy chirped, pulling Charlie’s bag from his hand and throwing it over his shoulder. Charlie followed, thinking he really would need a scale to say with confidence which was larger, the boy or the bag.

When they were a decent way from the station, the boy looked back over his shoulder.

“Those men are miners on strike, sir. They hear you say Platte Street, they might take you for a Pinkerton and on the side of the company. Might think to lay hands on you.”

“Then I thank you for my deliverance,” said Charlie. “How long has the strike been on?”

“Off and on for months. This one here? Fortnight or so.”

They walked a moment in silence.

“You are one, aren’t you, sir? A Pink?” The boy asked quietly.

“If I am?”

“What a man does with his time don’t concern me, sir. What does is if he’s the kind that would show appreciation for being carried without delay or inconvenience direct to his destination after a long train journey.”

“You’ll find me that kind of man.”

“Very good, sir.”

Both were true to their word. Hardly ten minutes later they had arrived at a brick edifice that overlooked the river and bore a sign with the word “PINKERTON” and the agency’s symbol of the ever-open eye on it. The boy took Charlie’s coin, pulled off his hat, and pledged that should Charlie ever need him again, he could be found almost any time at the train station and would be proud to serve.

The Pinkerton regional office was largely and, Charlie thought, almost certainly deliberately unremarkable; if the agency chose real estate to convey an impression of understated solidity to clients, it could hardly have done better. The exception was the door, a heavily reinforced iron object that would have done credit to a castle. It swung open to reveal an affable junior clerk who knew who Charlie was before he’d introduced himself, smoothly relieved him of his bag, and welcomed him into the office.

Charlie’s eye quickly took in the public areas - sitting room for clients, receiving room for trade and deliveries - and his glance lingered on the armored shutters adorning the windows, the first he’d seen in a Pinkerton office anywhere. The young man followed his gaze.

“There have been some disturbances,” he said, as if in apology, and gestured upstairs.

The door to the trade and deliveries room opened and another clerk pushed through, carrying a box; before it swung closed, Charlie glanced in and unexpectedly locked eyes with a man who sat on a run-down sofa next to a small stove. This still, compact figure was holding up a newspaper that obscured his face from the bridge of his nose down, but dark eyes behind reading glasses caught Charlie’s and held them intently for a moment. Then the piercing eyes became impassive, as if they’d learned all they needed, and with a slow blink, the man went back to his paper.

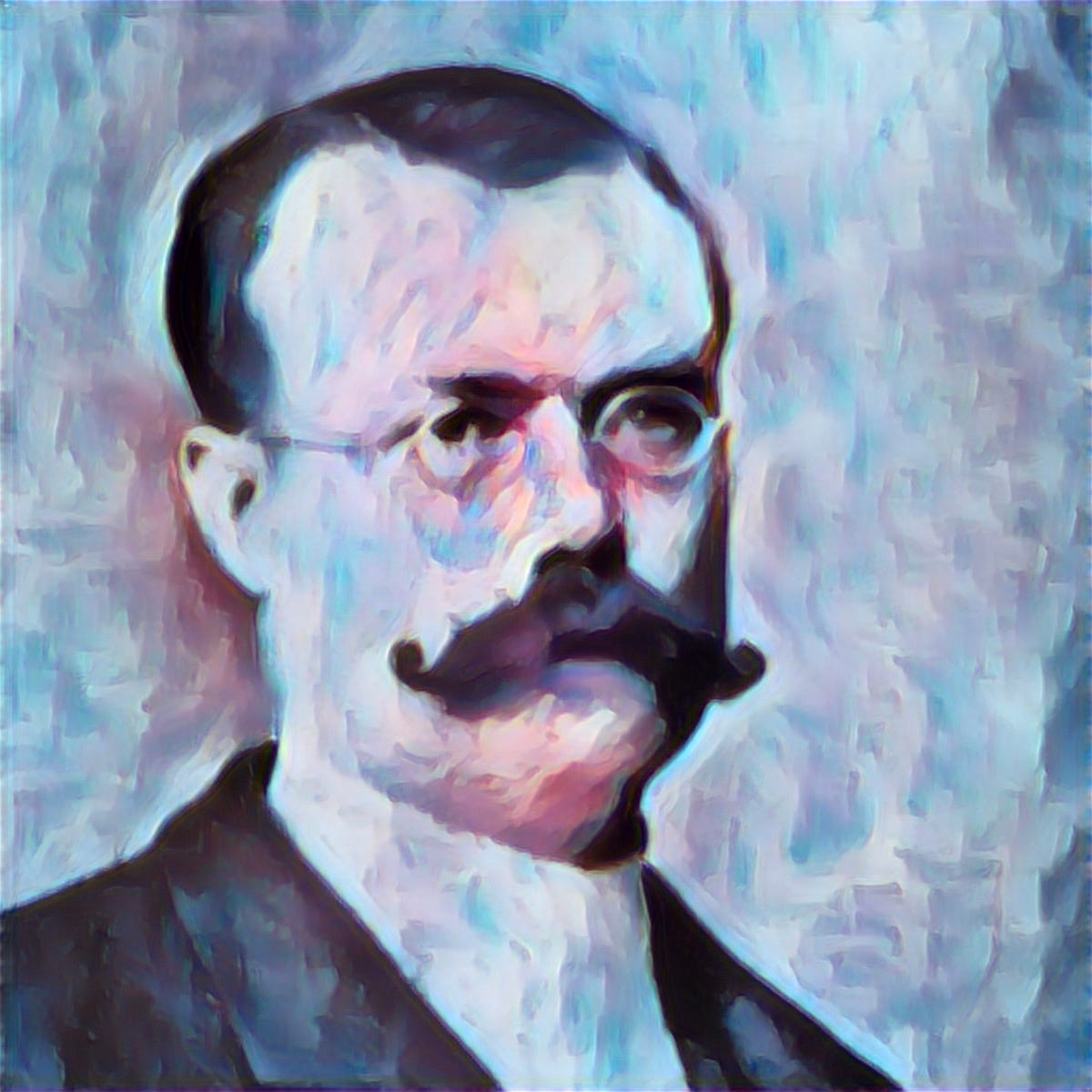

Shaking off the feeling that someone had walked over his grave, Charlie proceeded up the stairs and into the office of regional superintendent James McParland, a man whose mustache and physique gave him the aspect of an unusually vigorous walrus. He rose from his desk, seized a bottle of whiskey and two glasses, waved the bottle at a small table and chairs, and in the harsh tones of Ulster bid Charlie sit down and hear about the goddamndest robbery in Christian memory.

**

“Have you ever heard the like, Mr. Antrim?” McParland demanded, then drained what was left of his glass.

Charlie confessed he had not.

McParland looked thoughtful as he refilled his glass and Charlie’s. “Antrim. No distance from the county of my own birth. But you are not from there, sir?”

“I am not, sir.”

“Your father, then?”

“No, sir.” Quite otherwise, in fact, Charlie thought, but did not care to share this. “Farther back. I don’t rightly know, I’m sorry to say.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said McParland. “We’re neither of us there now. What say we drink to the old place anyhow?” and they did.

Charlie found he was taking a real liking to this McParland. He’d known the superintendent only by reputation; McParland been a policeman and owned a liquor store in Chicago until one or more of the O’Learys (or their livestock) had burned him and a hundred thousand other people out in the Great Fire, whereupon he became a Pinkerton and a damned good one, that much was clear.

Among other achievements, he’d infiltrated the previously impenetrable Pennsylvania sect of the Molly Maguires - a group of Irishmen that functioned as something between a miners union, a secret society, and an outright criminal gang - and broken them, much to the satisfaction of various anthracite mining interests. This had been well before Charlie’s time but he’d encountered a few of the scattered Mollys during his own work in Appalachia, and if the rest of the organization was anything like those paranoid, hostile, clannish bastards then he could only marvel at McParland’s skill and daring.

When a disgruntled former Pinkerton agent named George Thiel started a branch of his own detective agency in Denver in 1885, the Pinkerton brothers had opened their own, not because Thiel was a genuine threat to their business but because they would be goddamned if they’d concede an inch to that ungrateful sonofabitch. They did not ask that the Denver regional office make much money - at least not initially - so long as Thiel was discomfited, but they did ask that it not lose too much, and when this proved to be more than the superintendent, a man called Eames, could handle, the Pinkerton brothers called in McParland, fresh off breaking a railway strike in Kansas. The Irishman’s short, sharp investigation revealed that money, quite a lot of it, had been coming into the Denver branch, where it promptly disappeared, never to make its way to the Pinkerton National Detective Agency or even appear on a balance sheet. This resulted in the firing of everyone in the branch bar a single agent and McParland himself, who was given the Denver office and the entire western region to run according to his own methods. These, apparently and to Charlie’s delight, included punctuating his conversations with drams of whiskey.

“So you’ve been sent here to help us bring God’s judgement on the erring and the wicked,” McParland said, contemplating him from across the table.

“I don’t know much good I’ll do on that count,” said Charlie. “I was made right out of the station by a boy who couldn’t have been older than nine.”

McParland seemed amused. “A street urchin is a better judge of character than many an outlaw. Or so we are to hope, anyway, if your time here is not to be distressingly brief.”

Charlie could not help but agree. “Amen.”

Refilling their glasses yet again - here, here was a man who knew how to treat cases of old wounds and exhaustion, Charlie thought; he really should be a doctor - McParland sighed. “I’d like nothing so much as to set you to work on the miners unions directly, this instant. Anarchists, with no respect for law given down by God, or property won by hard work of brain and hand. Papists, too, a good many,” he said with distaste.

For a moment Charlie heard the sound of pious murmurs, smelled old, blackened wood, and felt the warmth radiating from a small adobe building in the bright, clear autumn sun. He looked down into his glass; if his eyes flashed, the whiskey did not reflect it.

McParland continued. “They’re why you were sent out here. But they’ll have to wait.”

Charlie recovered himself with a cough. “Because we have an outlaw problem. Or a client with an outlaw problem.”

“We do.”

“The bank?”

The big Irishman guffawed. “They’re putting their faith in the marshal, I suspect because they pay a fair portion of his salary. Good money after bad, if you ask me, but there it is.”

“The meatpackers, then.”

“The Hollander Meat Packing Company, exactly so. They’d like for us to identify the criminals responsible and bring them to justice.”

“And recover the money,” Charlie added.

“If possible. They are less intent on that point.”

“They’re just going to give the rancher the same again out of their own pocket, and don’t much care if they get it back?” Charlie shook his head. “Something rotten there.”

“My first thought as well,” agreed McParland. “It’s no trivial sum, too much even for a company of that size to write off twice. I thought it was an inside job of some kind. But - and here we stray into matters a bit outwith our charge - Hollander’s position is that they fulfilled their contract with the rancher; they provided security as agreed, from the moment they disbursed the funds until the moment the cash was stolen. That their security provisions proved inadequate is, they say, beside the point. They will not pay the rancher twice for the same beef, say they, and he must bear the loss.”

Charlie whistled.

“The work of God’s own brazen smiling serpent, isn’t it?” McParland said. “Their argument hinges on the contract saying they are responsible for providing security for the cash, not that they are responsible for its security. It might not hold up, but that’s not the point; they’ll have this case put on the slow boat, and of course they have an ironclad contract for the rancher’s beeves.”

Charlie contemplated the prospects for a rancher who had just lost his entire stock without being paid for it and was locked in a protracted legal fight against a company with counsel on retainer. Alas for his ass.

“Of course they’d prefer for us to return the funds,” McParland went on. “And we would very much like that, too, because we get a recovery fee. But what’s got Hollander worried is that this robbery against them was not the first.”

The big man rose and went over to his desk to procure a sheaf of papers.

“It started a few months ago. Hollander has agents who go on circuits from Montana to Mexico, making deals, scouting stock. They started coming up robbed on the road. Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas - it’s all there,” he said, dropping the papers on the table and resuming his seat. “One had a strong box stolen from his lodging; a particularly unlucky sod was ambushed and shot; most were set upon unawares, beaten, rolled by men they barely saw. What these men have in common is that they were all carrying some form of payment for beeves."

“Much cash?”

“Some. Their agents usually carry bank draughts, receipts for financial transfers - paper that would be useless to anyone but the rancher meant to receive it. A few of the ambushed agents had bearer-bonds or cash, in one case quite a lot - losses the company simply had to eat, and a jolly time swallowing it I’m sure they had. But for the most part the robberies were small affairs, and between the jigs and the reels, Hollander assumed the violence was the real point, relations between the company and the local stockmen being what they are. I’m sure you’ve heard.”

“What did Hollander do about it?”

“Nothing. It seems the preventative measures they considered were all more expensive than writing off their losses and replacing the lost agents.”

Doing nothing, in Charlie’s view, was a better plan that it was generally given credit for. It had the virtue of simplicity and resulted in surprisingly little paperwork. It was also a personal pastime that he found surprisingly to his taste. More to the point he’d spent years being paid by clients to disrupt the plans of miscreants who would have just gotten themselves shot or passed out drunk on a rail track or gotten kicked in the head by a horse in short order anyway if left to their own devices, saving everyone a lot of time and effort. Nothing had a lot going for it.

But it was a luxury, and one to be indulged carefully, weighed against other options and considered fairly. To indulge in doing nothing merely to save money not only invited more expensive problems later, Charlie felt, but cheapened the whole exercise.

“This robbery, though,” McParland continued. “No one would go to the trouble this lot did unless they knew the bank was guarded and they knew it had something of real value. They knew about the Hollander money, which puts the string of robberies in a rather different light for the company. We’re to serve justice on the robbers and uncover how they know so much about Hollander’s business. If we can get some of the money back, so much the better.”

Charlie dearly hoped that he hadn’t come all the way to Denver just to be sent back to Kansas City to go undercover with Hollander - the agency would surely cover that angle somehow - but kept silent; his particular commission was clearly on the horizon.

“There are clearly two elements to this investigation,” said McParland. “One is in Kansas City, inside Hollander. We have a man in there now.” Thank christ. “The other is the gang.”

Charlie nodded enthusiastically (not to say gratefully). “Any chance of identifying them from their descriptions?”

“Oh, we know who they are,” said McParland easily and to Charlie’s astonishment. “Some of them, anyway. The ‘father' in this little drama is one Tom Coleman, River Tom to his friends and admirers. We know the ones in the bank, too. All there.” He waved a hand at the sheaf of papers on the desk. “The problem is that we can’t find them, and even if we could, there are some questions we’d like answered before we put them in a position where they might do something extreme. That’s where you come in, of course.”

Here it was. Alright, let’s have it.

“You’re to go in cover and get as close to them as you can. No one expects you to get inside the gang, mind,” McParland quickly added. “But close. They lay their heads somewhere. They buy their whiskey somewhere. One of them has talked to someone. We need to know how they know about Hollander. And…there are some other irregularities here.”

Charlie cocked his head, but McParland declined to go on and instead refilled their glasses.

“There’s a man waiting for you downstairs. His name is Angus Thorn.”

“I believe I saw him on the way in. Another agent?”

“No,” said McParland emphatically. “Not at all. He’s a…a contractor, of sorts. He’ll tell you more about these characters and I think you’ll see what doesn’t sit right about this whole business.”

Charlie made to rise. “I’ll call him up -”

“You will not call him in here,” said McParland hastily and with evident dislike. “No. He’ll guide you on your way to Oklahoma; you’ll have ample time to talk, oh yes. He may take you via his bolt-hole south of here in a little mining Gomorrah called Valle Verde. Mind you don’t linger, for it might imperil both your professional prospects and your immortal soul, the priority of which I’ll leave to your private conscience. You’ll keep me updated per protocol, of course, until we’ve plumbed this matter and the gang has been consigned to the tender mercies of the law or the less gentle hand of a just and vengeful God.”

McParland raised his glass expectantly. “Clear?”

Charlie nodded, and they drank to justice and damnation.

Subscribe to The Experiment to keep up with future chapters of Regulator. Check out Frank Spring’s previous contributions to The Experiment which include “Neither Gone Nor Forgotten,” “Oh, DaveBro,” and “In Praise of Gold Leaf.” For legal reasons, I want to make clear that Frank Spring owns the rights to Regulator, free and clear. Follow him on Twitter at @frankspring.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback this June!