Making a cover story hold up goes a lot better when you’ve got the Pinkerton’s on your side. They can be very persuasive at the Western Union.

by Frank A. Spring

Billy Roann sized up Charlie as he emerged from the basement, and spat. “So you’re a friend to Violet and Davy?”

“I am, sir,” said Charlie. “And you must be Billy.”

“I must be,” said Billy, “and I’m afraid Violet and Davy ain’t been around here lately.”

“Any idea where I could start looking? I ain’t ashamed to admit I’m afraid of what Davy and Salt Lick might do if they think I didn’t make every effort.”

“Least you got the sense to be afraid of Davy and Salt Lick,” said Billy. “But I guess I couldn’t tell you where they might be. I’m tempted to kick you all the way out but a stranger comes in here talking about our sister and Davy O’Connell and them is not someone I’m prepared to throw back in the creek just like that.”

“Fine by me. If it’s all the same, I’d as soon linger a bit and let that marshal haul his freight a ways,” said Charlie. “Fucker’s like to kill me on sight.”

“On sight?” Dal asked. “Hell did you do to him?”

“Remember I said we had a little tussle, him and me?” said Charlie, reaching into a pocket. “I didn’t exactly leave it empty-handed.” And from his hand he dangled a gold watch.

Stunned silence, then an eruption of laughter, Dal slapping him on the back.

“I am dead certain you are more trouble than you’re worth,” said Dal, “but damned if that trick don’t call for a whiskey.”

Night had fallen when Charlie all but fell out the back door of Roann’s Meat & Grocery. He caught himself on the door frame with a laugh and called back over his shoulder, “when I get back I’ll tell you the one about the Shawnee lady!” and stumbled out into the dark, trailed by hoots of anticipatory laughter. He made his unsteady way to nearby tree, and beneath its branches fumbled with his belt buckle as his voice rose in song.

“Come and sit by my side if you love me/” he crooned, “do not hasten to bid me adieu/ but remember the Red River Valley…”

“And the cowboy who loves you so true,” came a harsh, grating whisper from several yards beyond the tree. Charlie looked back over his shoulder. No one.

“Come up a little closer,” he whispered. “Stay down.”

A creeping, low rustle, as if an enormous badger were stalking up to Charlie.

“Anything?” whispered Angus Thorn from the grass.

“They know where Violet is,” Charlie said, his voice even. “Still pretending they don’t but Billy and Dal had an argument off to the side and Billy said he didn’t want to wait two weeks for an answer, so I expect she’s a week’s ride off, probably Kansas or Nebraska.”

“Answer to what?”

“If she knows me,” Charlie said. “I get the sense Billy’s making up his mind about whether it’s worth sending a telegram. If they do, it’ll be Bee they send - they make him do all the scutwork.”

“And if they don’t?”

“They’ll just kill me and be done with it,” said Charlie. “You know what Bee looks like?” he went on before Thorn could object, and described the youngest Roann. “Either way it’ll happen soon.”

“I’ll get to it,” said Thorn.

“Good luck,” said Charlie. He made a show of struggling to hitch his belt again and unleashed some drunk-sounding profanity into the night air before making his weaving way back to the door, where he found Calvin Roann waiting. How long had he been there?

“You alright?” Calvin asked, looking him over.

“Never better,” said Charlie as he stepped with exaggerated care into the building. “Not at all ever better.”

**

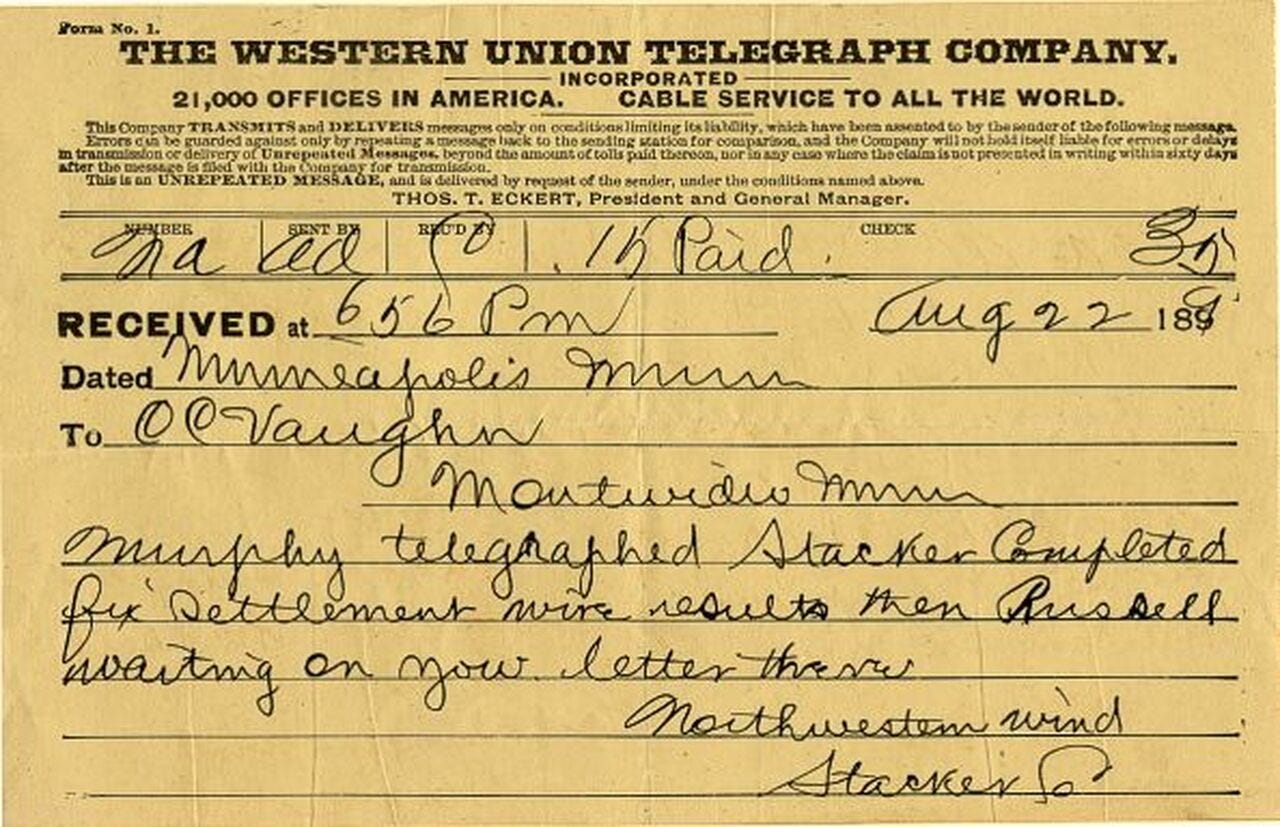

The Western Union Telegraph Office was less an office than a glorified closet. The company had been of two minds about having an office there in the first place, no bigger than Pawnee was, but it was still more than just a wood and water stop on the train line and so in the end Pawnee crammed the cheapest operators it could get away with into what was effectively an attic, albeit with separate entrance, above the town’s actual grocer. Anyone who could leave the job generally did as soon as they could.

The man who presently held the job, Hudson, was tolerated in town for his discretion, his reliability as both a telegraph operator and inveterate drunk, and his remarkable ability to keep his two callings separate. On duty, he was punctual and accurate; off-duty, swaying and speechless.

Bee Roann was therefore not entirely surprised to find the telegraph operator looking a little the worse for wear that morning, though he usually was not so ferret-eyed and tense no matter how big a load he had carried the night before. Bee, however, was in no position to judge, being himself in ragged shape, and as things stood his only priority was to have this message off and then get back into either bed or the hair of the dog as quickly as could be arranged.

“Mornin” he croaked out.

Hudson nodded. “Where to?”

“McCroom, Nebraska,” said Bee, rubbing his eyes. “Deliver to Miss Violet Roann, The Elm Hotel.”

“Message reads?”

“Urgent please confirm-“

“‘Urgent please’ or ‘urgent stop please’?” interrupted Hudson.

“Urgent stop please,” said Bee. “Goddamn.”

“Go on.”

“Urgent stop confirm you friend of Charlie Johnson stop here looking for you stop repeat confirm friend stop repeat urgent stop Bee full stop. That’s B-E-E.”

“…stop Bee full stop,” read the operator back, and told Bee the total charge. “I’ll get the response to you as soon as it comes in.”

“Thanks,” growled Bee, setting his teeth before pushing back into the blinding sun. The operator sat for a while looking at the message on his desk. When enough time had passed for even the most crapulous and enfeebled of the hangover-stricken to have disappeared down the lane, the little office’s door opened again and Guerra and Thorn walked in. Hudson looked at them with red, resentful eyes.

“Finished whatever this bullshit game was, have you?” The sour operator asked, sourly.

Thorn scanned the street through the window while Guerra gave the the operator a look.

“Mind your manners,” he said.

Hudson contrived to look both penitent and aggrieved.

“All I can say is you better be who you say you are,” said the operator, “or you’ll have to answer to the Western Union Telegraph Company.”

Guerra and Thorn exchanged a look that suggested they didn’t know whether to laugh at the man or pistol whip him. “Ese vato,” Guerra muttered, shaking his head.

“You want me to send this?” The operator asked, pointing to Bee’s telegraph form on the desk.

“No,” said Guerra, and snatched it up. “But you can send two others for us, and then your dumb ass can decide if we’re imposters.” He looked up at Thorn and waved his hand grandly. “Please, andale pues.”

“Denver, Colorado,” Thorn said to the wretched operator. “Deliver to James McParland, Regional Superintendent. Pinkerton National Detective Agency Offices, Platte Street.”

**

Charlie had felt better. Early in his career as a cowboy he’d learned to hold his whiskey, and he’d found the ability to drink a great deal and remain reasonably clear-headed to be an extremely useful skill when he became a Pinkerton. Later, he learned how to appear to be drinking a great deal when not actually drinking much at all, a skill so much more useful than the previous one that he kicked himself for not adopting it sooner. Which was not to say that he was averse to a skinful, when called for, but there was a tool for every task.

Even so, you cannot keep company with a numerous band of large, thirsty, and obviously murderous individuals seemingly hellbent on drinking all the whiskey in town without getting a fair amount of it down you, and the ill-effects of this, plus the fact that he had slept in some sort of trough in the basement of the Roanns’ place, always at least nominally watched by one brother or another, made the following day a bit of a trial. The Roanns were surlier than usual to him, although he had the strong impression that this suggested they liked him more than they had and not less. They certainly fed him well, periodically handing him great slabs of meat, each of which, he was forced to admit, was better than the last.

All day he heard the Roanns go about their business, including serving a few customers, whom Dal treated with great courtesy. He was watched by different brothers at various times, which gave him a chance to probe all of them, and he concluded that Calvin was his pony. He was not the most talkative - that was Bee, who resented his position at the bottom of the family hierarchy so much that Charlie would normally have gone to work on him straight away but for the fact that he doubted Bee would ever actually do anything about the many grievances to which he gave such extravagant voice.

Calvin, though, seemed just lost. Billy was the leader, Dal his (occasionally fractious) second, George was the heavy, and Bee was the runt. Calvin had no role; he could neither exercise leadership nor enforce it, and even to persecute Bee he had to wait his turn. When Calvin kept an eye on Charlie, they talked, and he seemed both interested in his prisoner and pleased when Charlie showed interest in him.

Charlie mainly kept their talk on cattle, partly because Calvin, whatever his discontents with the Roann power structure, genuinely seemed to love the cow bidness, and partly because Charlie had a fund of engaging and anonymous stories from his time as a cowboy on which he could draw without taxing his pounding head too much.

It was some time in the afternoon when Calvin began to tell him with great satisfaction about his plans for a small herd of shorthorn hybrid cattle the Roanns were expecting. Charlie’s attention was beginning to buckle under the weight of detail - the best cuts to expected from these animals, how they differed from the common run, how to prepare them, and so forth - but he put a good face on it and looked engaged.

“Where’d you get the animals?” He asked idly.

Calvin puffed up a little. “I got us a good price from an old boy in Alfalfa County,” he said. “He’d just had a big deal with a meatpacker fall through, and I swooped in and took advantage.”

“That was handy for you to know,” said Charlie, “and dumb of him to tell you.”

“Didn’t hear it from him,” said Calvin. “He might be deaf as a post and crazier than a shithouse rat, but he ain’t stupid. We heard about it from a friend.”

Charlie took a silent deep breath to keep his voice even. “Must be nice, having friends in the meatpacking companies,” he said casually.

“It has its advantages,” said Calvin with a chuckle. “Expensive at first, oh yes. But I said it would be a good investment.”

“Well, I should think,” said Charlie. “I expect it’s been well worth it.”

“Oh, yes, yes,” said Calvin with another chuckle.

“Well, that’s main clever of you, I think,” said Charlie. “Main clever.”

Subscribe to The Experiment to keep up with future chapters of Regulator. Check out Frank Spring’s previous contributions to The Experiment which include “Neither Gone Nor Forgotten,” “Oh, DaveBro,” and “In Praise of Gold Leaf.” For legal reasons, I want to make clear that Frank Spring owns the rights to Regulator, free and clear. Follow him on Twitter at @frankspring.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback this June!