Adam Hirsch has accomplished a lot of things in his life. Educated at the University of Texas and Harvard Law School, Adam’s apparently the top-rated business litigation attorney in all of Chicago. He’s basically Will Gardner from The Good Wife, except real, happily married with children, and not secretly in love with the wife of a disgraced politician. All that is fine, but to me Adam will always be my first intern at a job I had when I was 26. We’ve had adventures together, none better than seeing Mike Mussina strike out 15 over seven and two-thirds innings at Fenway, so when I was trying to make sense of Judge Coney Barrett’s evasive testimony I asked him for his perspective. This is his first contribution to The Experiment.

by Adam Hirsch

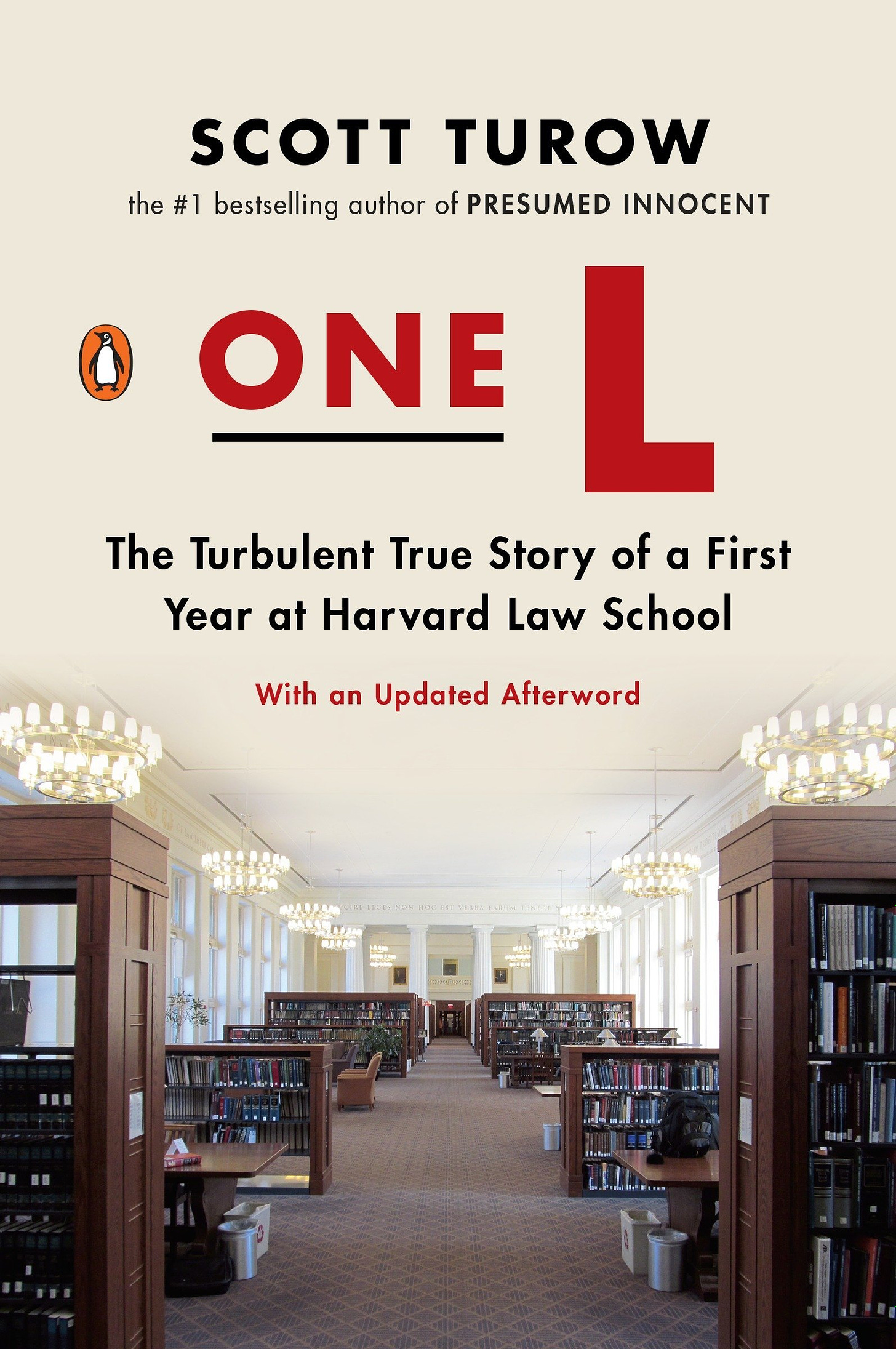

The first month of law school is an indelible memory. Mine was September 1998. I started straight through after graduating college the previous June (and after working campaigns with the proprietor of The Experiment over the summer). The centerpiece of my first year was a yearlong course in Civil Procedure taught by Arthur Miller. Prof. Miller’s first-year Civil Procedure course was immortalized in Scott Turow’s “One L” as one part intellectual adventure, one part high ropes course, and one part improv act. (Yes, yes, I went to Harvard Law School. My contemporaries included Tom Cotton, and the Castro twins. I just missed Ted Cruz and Kayleigh McEnany. Call it a push?)

Prof. Miller’s routine was to call on a single student at the start of his 90-minute class, and to keep that poor soul on the hot seat until he or she ran out of useful information. This was his version of the Socratic Method. By the end of September we’d seen successes and failures: some students crapped out after 10 minutes, others were able to run the table until the closing bell. It was still dark one morning when I struggled out of bed for Civ Pro, which started first thing. An autumn cold filled my sinuses, but this was Arthur Miller. Missing class was not an option. Plus, there were 140 of us. What were the odds he would call on me?

100%, it turned out. “Mr…. Hirsch, he said, dragging his index finger over the seating chart on his lectern, this case [International Shoe Co. v. Washington, a 1945 Supreme Court case on jurisdiction] came out of St. Louis, didn’t it?” “Yes,” I said. “Presumably before McGwire?” he added, archly. We were in the middle of 1998’s Great Home Run Race. I gulped. No guts, no glory. “No,” I said, “in 1945 in St. Louis it would have been Musial.” Gasps from the crowd. A smile from Prof. Miller. “Musial, yes,” he said, and then he rattled off the other 8 members of the 1945 Cardinals’ starting lineup by name. Touché.

Prof. Miller spent the next hour putting me through my paces on International Shoe. Due credit to the Day-Quil for an assist, but I did OK. We talked through the case’s “minimum contacts” rule for personal jurisdiction, which still applies in large part today. After class, I got backslaps and kudos from my classmates, which felt good. I went back to my dorm room and slept through that afternoon’s torts class.

Watching judicial nominees answer questions from the Senate Judiciary Committee brings back memories like this one. The nominee is put on the spot, and is asked doctrinal and hypothetical questions about case law past, present, and future. In preparation for Civ Pro, I read hours of cases and prepared pages of typewritten notes. International Shoe was not a surprise to me, because it had been assigned in advance. Nevertheless, the nervousness I felt when called on was nuclear. I was immediately put on stage in front over 100 mostly strangers and a law professor who had literally written the book on Civil Procedure. My performance in class was ungraded, but that didn’t matter. I wanted to impress Prof. Miller, I wanted to impress my classmates, and I wanted to prove to myself that I could play the game at the highest level. So I swung at the first pitch, hard.

I didn’t see Judge Coney Barrett take her bat off her shoulder.

I didn’t see the same nervousness or need to impress from Judge Coney Barrett last week. I didn’t see her take her bat off her shoulder, really. To be fair, this wasn’t unique to her. For recent Supreme Court nominees, the doctrinal portion of their hearing has been contentless. (I am not commenting on the personal conduct portions of these hearings, which are a different thing). Friendly Senators don’t want to rock the boat, so their questions aren’t intended to produce answers. Hostile Senators can ask about past cases, past rulings, or points of law, but the nominee’s dodges are well-honed. Sen. Klobuchar asked, “Judge Barrett under federal law, is it illegal to intimidate voters at the polls?” Judge Coney Barrett’s response? “I can’t characterize the facts in a hypothetical situation and I can’t apply the law to a hypothetical set of facts.” Sen. Klobuchar then read 18 U.S.C. 594 into the record. That statute outlaws anyone who “intimidates, threatens, coerces or attempts to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any other person for the purpose of interfering with the right of such other person to vote.” The nominee’s response was, in part, “It’s not something really that’s appropriate for me to comment on.”

“It’s not something really that’s appropriate for me to comment on,” was not an answer I felt was available to me in Prof. Miller’s Civil Procedure class. Buy why? Why did I prep for hours so I could bring to bear a working knowledge of mid-century National League baseball and personal jurisdiction, but a nominee for the Supreme Court can simply refuse to answer questions when it suits her? Why is a first-year law student more open and forthcoming, more willing to engage in Socratic dialogue, then someone nominated for a lifetime appointment to the most powerful court in the country?

The answer, simply, is power. Whether I could answer Prof. Miller’s questions didn’t matter in any real sense. It wasn’t going to affect my grade, and it wasn’t going to affect his opinion of me (he had none). What Prof. Miller had over me was power: the power to scare, the power to intimidate, and the power to embarrass. The social/academic pressure I felt was real, and it pushed me not just to prepare, but to perform. I didn’t want to let him, my classmates, or myself down by screwing up or not answering. I wanted the approval of everyone in that room, even if it only lasted the length of the class.

Where does the power lie in a Supreme Court hearing? The Senators do their damndest to make it look like they have it.

Where does the power lie in a Supreme Court hearing? The Senators do their damndest to make it look like they have it. They sit up high on a dais and put the nominee down in a pit behind a table. They swear the nominee to tell the truth under penalty of perjury, and once upon a time, at least, there was a threat that a stonewalling nominee might not get confirmed merely because he refused to answer Senators’ questions.

Those days, if they ever existed, are long gone. Last week, all power resided with the nominee. She had won the nomination in a competitive, opaque process that began, yes, in the first year of law school. She was smart, dedicated to her craft, and dedicated to the ideological movement that lifted her up out of academia and into an appellate judgeship. Because our political parties have sorted ideologically, and because her party has a majority in the Senate, Democratic Senators had no power over her. Their “no” votes are presumed, and therefore irrelevant. Perhaps Democratic investigators could have turned up an old op-ed, or a personal skeleton, but no votes were going to move as a result. The Democrats can raise the political price Republicans pay for rushing through her confirmation, but the Republicans have already made clear that they will literally kill themselves to confirm Judge Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court.

That Republican single-mindedness gave even more power to the nominee. She knew that her 50 “yes” votes were certain, regardless of how she answered their questions. She also knew they want to rush her confirmation before November 3. The past four years have taught everyone that Republican Senators have a high tolerance for public humiliation and incoherence. Judge Coney Barrett could have done a Sarah Cooper lip sync routine or Harry Anderson’s greatest hits from “Night Court” and she’d still have 50 votes for confirmation. Why didn’t she answer Sen. Klobuchar’s question? She had the power not to.

More than 20 years later, the true lesson of that Civil Procedure class has nothing to do with personal jurisdiction.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.

Want a way to send gifts and support local restaurants? Goldbelly’s got you hooked up.

I used this to order scotch delivered right to my door. Recommend.

I’ve lost 35 pounds this year with Noom, and haven’t had to cut out any foods. Noom is an app that uses psychology, calorie counting, and measuring activity to change your behavior and the way you think about food. I’m stronger and healthier than I’ve been in years. Click on the blue box to get 20% off.

Headspace, a guided meditation app, was a useful tool for my late-stage maturation has been a godsend to me during the pandemic. Click here for a free trial.

If this newsletter is of some value to you, consider donating. Honestly, I’m not doing this for the money. I’m writing this newsletter for myself, and for you. And a lot of you are contributing with letters and by suggesting articles for me to post. But some of you have asked for a way to donate money, so I’m posting my Venmo and PayPal information here. I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some of the most fun I’ve had. Venmo me at @Jason-Stanford-1, or use this PayPal link.