Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil MoPac

How a satirical Twitter account became the conscience of Austin

Seven years ago this month, evil came to Austin in the morning. A forty-something office worker got up and planned his commute. “I jumped on Google and saw that that MoPac was backed up as bad as I had ever seen it in about 15, 20 years. And, you know, I had just had enough.”

The idea, he says, came to him fully formed. After briefly considering a few different names, he signed up for a Twitter account named Evil MoPac and tweeted, “Greetings, Austin. I’m MOPAC traffic. How am I looking today? p.s. I hate you. p.p.s. Fuck off.” In effect, he started shouting, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” And he hasn’t shut up since. Now with more than 51,900 followers, Evil MoPac is a Twitter account that describes itself as a pro-gridlock activist.

Named for the oft-congested and hence evil highway in west Austin parallel to the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, Evil MoPac started as a satirical comedy bit about a malevolent roadway delighting in holding drivers hostage in traffic jams. But as the possible demise of Twitter has created something of an existential crisis for the account’s persona, Evil MoPac has become the conscience of Austin.

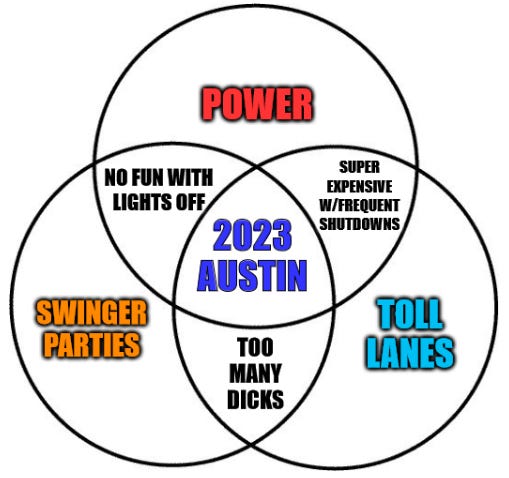

Now, some ground rules: The person I’m talking to is the dude who runs the account. He often gives interviews speaking as if he were Evil MoPac; this isn’t that. He’s speaking for himself, but his job situation would not be improved if they found out that he was running a famous left-leaning Twitter account that called Elon Musk fans “taintlords” and mocked the swinger scene in Steiner Ranch, an upper-middle class area southwest of town.

Recently, Evil (the roadway persona, not the dude) joined the Lawrence Wright chat on its Substack Under Construction with Evil MoPac with the essay, “Does Austin Actually...Suck?” I thought the existence of Evil MoPac and the role it plays in civic life in Austin proved Betteridge's law of headlines and offered evidence that Austin was, in fact, still weird, and I’ve grown interested in how this person created an online character that has become seemingly sentient.

A traffic reporter for one of the local TV stations noticed right away and riffed with Evil MoPac a little.

“And I'm like, this is kind of fun,” said the man who had just given birth to Evil. He enjoyed venting his spleen to the Twittersphere despite only getting one or two likes a day at first. In the beginning, the catharsis was enough. “That sort of distilled it down to being a labor of love rather than something I was doing for my ego or something that was gonna get me Austin famous or anything like that.”

This was a bad time for drivers on MoPac, which was undergoing a long-overdue renovation to add a toll lane. The project had missed deadlines and blown past budget projections.

“The toll lane was sort of my stock and trade that first couple of years or the fact that it was late and there'd be one dude working with 25 people watching and that sort of thing,” he said.

People were pissed, mostly at Steve Adler, then the Mayor of Austin. This was unfortunate for two reasons: The City of Austin did not own the road and had no role in the construction project, and I was the Mayor’s communications guy.

I hated Evil MoPac and would get angry when anyone would say how funny it was. Most people in Austin in 2016 were angry at traffic. I was angry at a Twitter account that encapsulated the zeitgeist in a comic way that I just found intolerable. Looking back, it’s really funny how angry I got about it.

“I vaguely recall you not being a big fan in the early days,” he said. He liked to poke Adler about non-traffic things, too. I seethed. “But if I didn't do that, it wouldn't be true to the account. I don't care who the mayor is.”

Eventually, even the Mayor’s office bowed before the growing fame of Evil MoPac.

“I don't know if it was Adler or probably you who eventually followed the account. We got some back and forth. It was pretty fun,” he said. “I'm not getting that with [current mayor Kirk] Watson. I mean, I know Watson has bigger fish to fry right now, obviously. He's probably deeply regretting becoming mayor. But I'm not sensing that he is embracing the Evil MoPac thing right away, but it's okay. I mean, if it's a one-way street, I'm happy to do it.”

Let us pause briefly to note that in a city constantly interrogating itself about whether it is still weird, it’s normal if not expected for the mayor to engage in digital conversation with an online persona for a road. No one thinks that is weird at all.

People in Austin liked the account because it fit perfectly with our illogical belief that traffic is somehow imposed on us when we're in traffic. If you get up and you're getting in a car at the same time everyone else is, and you're driving on the same road in the same direction everyone else is, it's not the road's fault. Evil MoPac absolved commuters for their participation and validated their frustration, but hashtag #NotAllDrivers.

“I, obviously and correctly, rip on BMW drivers a lot because statistically they are the worst,” he said. “Not just BMW drivers, but so many drivers in Austin drive and do that ‘weave in and out of their lane 26,000 times’ thing. Their time is worth more, they're more important, they're smarter. And I think it comes down to that. And I think Evil MoPac was itself push back against that mindset.”

Not everyone adores Evil. Among the account’s detractors are, he says, the kind who believe that “Austin is a homeless-infested hell hole” and “if you don't venerate everything the police do, you're a villain,” people in Westlake, as well as “people who take it personally when I rip on Tesla or Elon Musk.”

“I think they should frankly worry about the car exploding or driving into a schoolyard without them driving,” he said. “I think he's a idiot who's a sociopath and a narcissist and all that stuff. I don't think that's exactly a breaking news story.”

But to Elon’s battalion of flying monkey fanboys, Evil MoPac is saying everyone who drives a Tesla is an idiot.

“I just don't understand how they internalize it,” he said. “I think they all think they're gonna be friends with him, especially the Austin ones. They think he's gonna invite them over to his $20 million mansion he's living in, and they're gonna be bros. He doesn't like them, and he's never gonna like them.”

By telling people what they already knew in a humorous way that made the connection, Evil MoPac’s jokes got shared, and the more Evil spread, the more attention the account got. Evil MoPac started getting some press. When the account jokingly announced that the expansion soccer team would be called The Austin Gridlock, it made the news. Austin Monthly even gave Evil MoPac a byline for an essay on why the toll lanes on MoPac would not help congestion.

And as Evil’s fame grew, people speculated who was behind Evil MoPac. He estimates that as many as 10 people know his real identity. He’s been rumored to be a politician, a lawyer, PR hacks, spokespeople, and even actor Matthew McConaughey.

“A solid plurality of the guesses tend to be journalists,” he said. “This is some great insight into my ego, but I always tend to be not mad that they think someone's me, but then I'll go look at their tweets and I'll be like, ‘What the f*ck do they think that person's me for?’”

Becoming famous anonymously, he says, has allowed him to enjoy the secret that he is Austin’s Clark Kent, standing around while people are talking about Superman. “That's sometimes me,” he said. Recently his neighbor was talking about Evil MoPac and jokingly accused him of being the person behind the account. “I'm like, ‘I don’t do Twitter.’”

Like I said, Evil MoPac started seven years ago this month. Almost exactly seven years before that, Twitter debuted at SXSW. Elon Musk’s move to Austin and bumpy takeover of Twitter endangers the existence of this particular persona. Evil MoPac also has an Instagram account and that Substack, but it’s a Twitter native. If Twitter goes down, the persona of Evil MoPac effectively dies.

In fact, Evil MoPac already tried to quit as Twitter looked to be circling the drain last December. Advertisers were walking away, and Musk was reinstating accounts that had been banned for offenses including racism, sexism, and being Donald Trump. It was time, he thought, for Evil to exit. “The End,” he tweeted.

“It had been festering for a while, but Musk banning journalists for tweeting public information, then lying about it against the backdrop of him reinstating the worst chuds on the platform [is why I quit],” he told Austin Monthly.

It wasn’t the end, but it could be nigh. After widespread staff cuts, the app has been glitchy. Two weeks ago, it went down around the world. Twitter could survive this transition to become a beautiful butterfly supported by subscriptions. Or it could crash. It would be ironic if Evil MoPac died in a crash.

Evil MoPac, a child of Twitter, is a fluently realized persona that exists on a platform that could go all explody. He didn’t like Elon Musk to begin with, and now the biggest taintlord of all has taken over his favorite platform and ruined it. He admits that he let it get to him too much.

“Ultimately — and by ultimately I mean three weeks later — after a lot of, a lot of soul searching, I concluded that Elon Musk is winning if I’m not on Twitter, if that makes sense. Not that I'm the French resistance or something, but the reality is it made me feel a little more empowered to get back on rather than trying to Reddit or Facebook my way out of this.”

And because this is an Austin story — Twitter comes out at SXSW, Austin dude gets famous anonymously as voice of angry roadway, becomes conscience of city, Evil Bajillionaire moves to Austin, buys Twitter, becomes Damocle’s sword over neck of popular persona — does this have any bearing on Austin’s endless self-examination of whether it still has any weirdness lint in its bellybutton? Is Evil MoPac’s role in the rise and fall of Twitter evidence that Austin is still weird?

“I think maybe a little bit,” he said. “I think it shows that in any big city like this, whatever its origin story, there's room for this kind of thing, and there's room for goofy, weird little things like this account that reflect what people are thinking. So yeah, I think that's true.”

He doesn’t get it. Other cities also have fake Twitter accounts achieve prominence. @MayorEmanuel, a hilariously profane depiction of then-candidate Rahm Emanuel, became a sensation on political Twitter in 2011. But that account had no role in civic life in Chicago. It existed only as a commentary on Emanuel.

Evil MoPac, on the other hand, exists in civic life by expressing a moral worldview about the city. No one thinks it strange that a satirical Twitter account has a sense of right and wrong or that it converses with elected officials. Credit belongs, of course, to the man behind the keyboard, but Evil MoPac exists independently in the life of the city, a fully drawn character in the story of Austin. And the fact that everyone in Austin thinks that is perfectly normal means one thing:

Austin is still weird, just not the way it was in the ‘80s.

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!

Nope

Replacing the phrase "stock in trade" with the nonsensical "stock and trade" was the aspect of the piece I found interesting. There might be an extra "is" in your newest sentence. I'd be funny about it if I could.