How Elon Musk may have just ruined everything

As a Black Mirror episode becomes real, the demise of Twitter has come at a really bad time.

Robots were an idea about robots first. The word “robot,” a fictional derivation of the Czech word for “forced laborer,” was coined in a play called R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots that dealt with the very human fear of being replaced by robots. Decades later, a Kentucky inventor patented the first robot. First came the science fiction, then came the science. So maybe it shouldn’t surprise us that the specific fear unleashed by the sudden arrival of ChatGPT was predicted with alarming accuracy almost exactly a decade ago by Black Mirror.

Black Mirror was a Netflix show about a near-future technical dystopia of unbearable bleakness. In “Be Right Back,” the first episode of the second season, a woman moves in with a man who is addicted to Twitter. The next day, he dies. Wanting to spare her grief, a friend uploads his digital footprint from Twitter and emails to create a chatbot that allows the grieving woman to text with him. Later, as technology advances, she created a lifelike android of her late partner, but more like than life. Because this is Black Mirror we’re talking about, the story ends in the creepiest way imaginable, with her keeping him in the attic, unwilling to terminate him, or it, but also unwilling to accept it, or him, as real.

So that’s where we began to replicate ourselves, by trying to cheat death.

A short time later, a man — this one real, flesh and blood, nonfictional — died in a motorcycle accident, so his friend, inspired by that Black Mirror episode, used their text chats to create a chatbot so she and their friends could talk to him. She started a business to launch an AI app called Replika, and soon she was not alone. Another created HereAfter AI. A journalist created Dadbot to allow him to continue talking with his dad after cancer took him. A man created a GPT-3 chatbot to allow him to talk to his dead fiancé. And then in 2021, Microsoft applied for a patent to turn dead people into AI chatbots — and not just your friends and relatives.

“The specific person [who the chat bot represents] may correspond to a past or present entity (or a version thereof), such as a friend, a relative, an acquaintance, a celebrity, a fictional character, a historical figure, a random entity etc. The specific person may also correspond to oneself (e.g., the user creating/training the chat bot).”

But these attempts at a kind of immortality had limitations. The chatbots were based on an if/then architecture, answers drawn from nested folders of subtopics and not a genuine intelligence. The effect was more parlor trick than Lazarus, as amusing and artificial as asking Siri to marry you, eliciting a coy, if canned response from a menu of stock answers. The proposal had no stakes because Siri was no more real than your cancer-stricken dad still lived.

Then came ChatGPT. Now you can set parameters and get an accurate representation instantly. Tell ChatGPT to write you a speech about Ronald Reagan in the voice of Ted Kennedy, and you got it. Want advice from Marcus Aurelius on the ethics of using ChatGPT to interact with dead people? Literally just ask him. Suggest a specific problem and ask for how John Wooten would handle it, and done. And now you don’t have to upload all the information. You just set the guidelines and set it loose.

You can use ChatGPT to automate tasks for you like shopping for the best deal on a certain model and make of vehicle and then negotiating the purchase for you. Have you ever joked that you wished there were two of you so you could get more done? Now you can do that and make the computer do all the boring stuff.

And yes, if you want to go back to the beginning and get all originalist, you can talk to a deceased loved one, except now AI can take into account all the probabilities and events since his or her passing. My grandfathers died in 1981; I am no longer limited to talking about the events of their lives. Now we could, if I chose to take this step, tell them about Donald Trump. I am not a monster and would never do this, but the point stands. If AI can pass the bar exam with flying colors — that is, not just replicate a legal mind but demonstrate one better than 90% of those taking the bar exam — we’re not just talking about mimicry but recreation of life thanks to an admittedly artificial but actual intelligence.

If AI can pass the bar exam with flying colors, we’re talking about recreation of life.

A friend — Sean, actually, from last week’s essay — compared this technological advancement to the discovery of fire. I don’t think that is making too much of this.

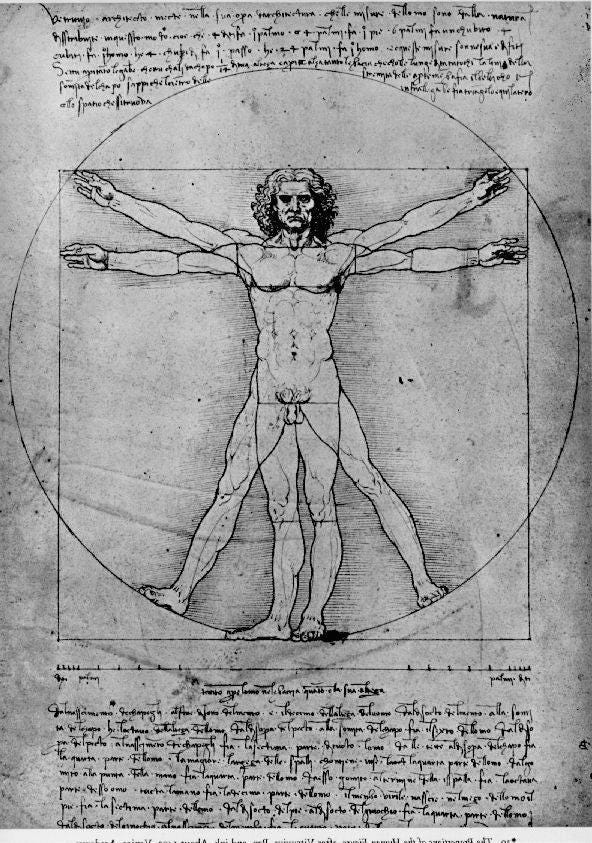

But I prefer another comparison I heard to artificial perspective. A long time ago, paintings were janky. Angles were off, objects appeared out of proportion, lines lost perspective. To be fair, artists back then often weren’t trying to recreate life but to represent divinity. It was more important to put Jesus and Mary in the proper size (to connote importance) than in proper proportions. The aim was to depict the godlike, not the lifelike.

Then, in 1415, an Italian architect named Filippo Brunelleschi figured out artificial perspective, also called linear perspective or mathematical perspective. As near as I can understand it, lines above the midpoint converged down to the midpoint, and the opposite was true for lines below the midpoint. This discovery represented a great leap forward in the Renaissance. Suddenly, given the new, expanded limitations of technology and scientific knowledge, it was possible to recreate reality as never before. Do you know what this means?

Leonardo da Vinci recreated mankind, or at least a kind of man in his proper proportions. It was not possible to draw the Vitruvian man before; suddenly it was.

So here we stand, we hairless apes, holding the strands of creation that AI has gathered together to give us the power to expand time vertically (by adding more hours in a day) and horizontally (by recreating life after death). This is where I think Black Mirror undersold our now present-day dystopia, because even those nightmare merchants did not imagine that Donald Trump’s monstrous presidency would be a prelude to the ascendancy of a more cunning, more malevolent, and more effective leviathan.

Though none of us knew it at the time, a mysterious new respiratory disease had just begun circulating in central China. This would set in motion a spectacular series of events that would make Twitter the focal point of pitched battles about freedom of speech, community health, racial justice and American democracy. At the same time, the pandemic and the federal response to it would create bizarre macroeconomic dynamics that would help one man grow his net worth tenfold in two years, transforming him from a high-profile but middle-of-the-pack billionaire into the wealthiest man in human history. For a time, anyway. It appears that Elon Musk was troubled enough by Twitter’s role in the discourse battles that he felt he should control it himself, and $44 billion later — nearly double his entire net worth at the outset of the pandemic — he has his wish.

The above is from Willy Staley’s excellent essay on the Twitter Era (h/t EJ), which he judges, perhaps accurately, as in its last days. A lot of pixels have been spilled on what we will miss when the virtual town square becomes a circus for Nazis, crypto bros, and badly targeted ads, and we’ve made great sport over how much money he has lost by erasing the value of blue check marks by taking them away from public figures and giving them to anyone with $8 a month.

Identify verification is ruined right at the moment that it is key. To recreate life is now easy, and essentially free. Do you want to create a chatbot so you can sext with your favorite actor or actress? Fine. I mean, creepy, but fine. But there is also nothing stopping you from launching that titillated virtual persona as a social media account, and now, thanks to Elon, you can pay to have it verified at the exact moment the real Natalie Portman or Pablo Pascal or Patrick Stewart (“That’s SIR Patrick Stewart!” yells S) had their blue check marks taken away.

For that matter, there is nothing stopping any of you from recreating a version of me that writes a different Substack newsletter that gets to the point sooner, and it’s this: I have no problem with technology that expands the possibilities of being human. And AI certainly does that. What worries me is that there are utterly no restrictions on this power, and the one person with more power than any human has ever had has recently devalued the one agreed-upon marker for the most important questions facing us right now. If we can recreate life so accurately as to confuse the distinction between reality and its representation, how can I prove that I am me, and do I own the rights to my replication?

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!