His own newspaper attacked him for his columns questioning a murder investigation.

Now, 30 years later, he's been vindicated. Why won't The Oregonian apologize?

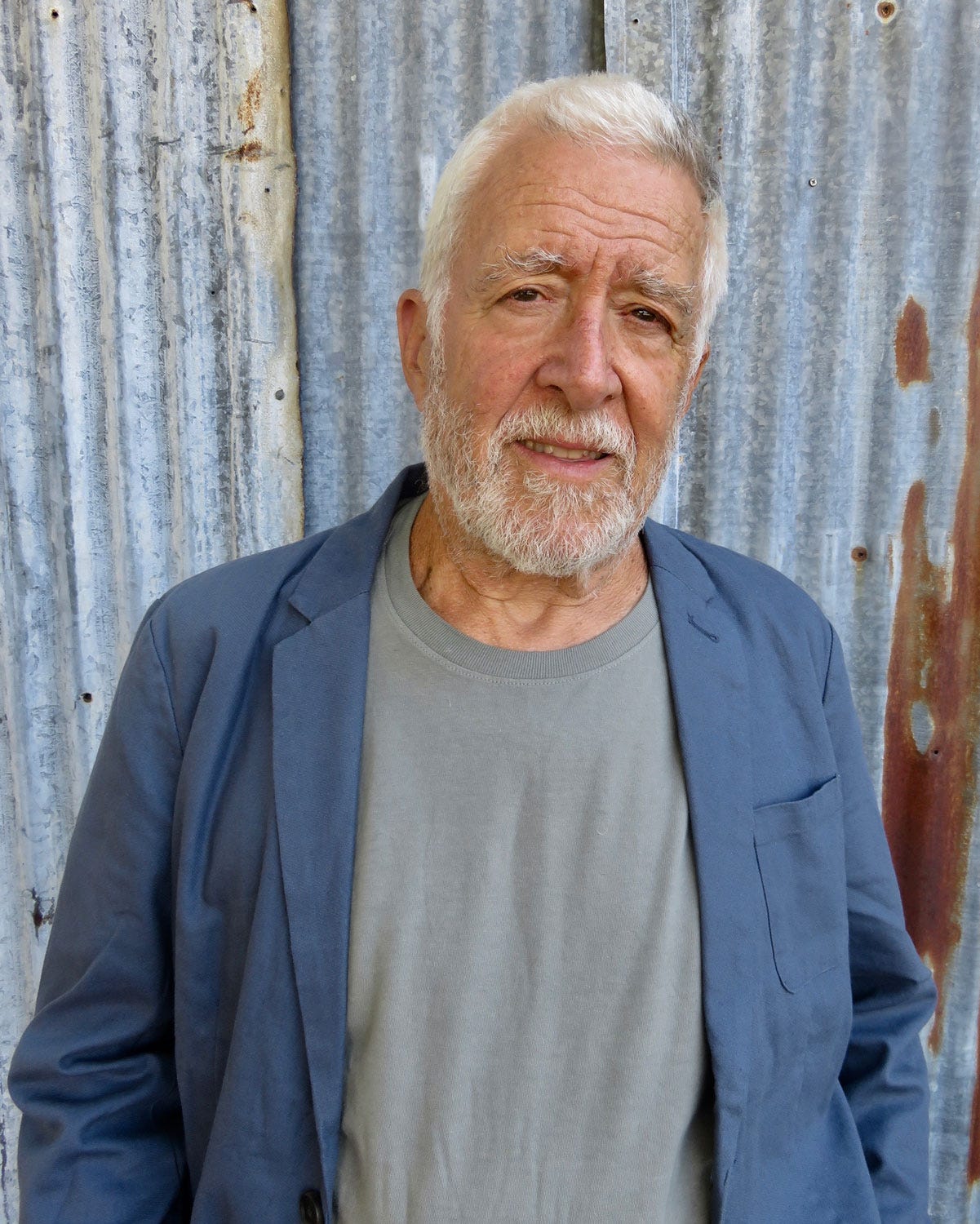

circWhen I started college in Portland in 1988, my dad was enough of a local celebrity that I’d often get asked if I was Phil Stanford’s son. He was popular enough as the metro columnist for The Oregonian that they put him in TV ads and plastered his face on newspaper vending machines. The ABC affiliate thought he was a big enough draw that they paid him $600 to come on every Friday to talk about his columns. The Oregonian did a poll to out what readers turned to most: In first place was my dad, or rather his columns that found empathy and value in stories of regular people living in the city. He was even more popular than the classifieds. Whenever we went out, people recognized him. He said he hated it, but I could tell he liked being famous.

Then Michael Francke was murdered.

Francke was the head of prisons hired by then-Gov. Neil Goldschmidt to reform and expand the state’s prison system. After investigating his own department and clearing house, Francke was all set to spill the tea to a legislative committee when in January 1989 he turned up at the office with a bad case of being dead on account of being stabbed three times in his heart. His body was discovered in the morning, so he was killed after working late. The police said he must have interrupted someone robbing his car.

My dad, no dummy, didn’t think that made sense.

When he was at The Oregonian, Stanford devoted 84 columns to Francke's murder and mentioned it in 17 others (one-ninth of his total of 898 columns over seven years), a staggering total of some 69,000 words--enough to fill a book. His repetitive drumbeat of stories all played the same theme: that the knife murder of the chief of corrections was not, as authorities ruled, a car burglary gone bad. Instead, Stanford argued, it was part of a larger conspiracy that reached at least into the Department of Corrections.

Mind you, he did this on the op-ed pages, breaking news in his columns missed by the news desk, which tended to report the official line. Not for the first time, he got a bad reputation in his peer group. “There was a huge division in the newsroom over this,” said a former colleague. “The prevailing wisdom at the newsroom--and I guess I was a subscriber to it--was that the whole conspiracy theory was bullshit.” He said this on the record for publication, which is a helluva thing to do to another colleague for the interminable sin of not accepting the official word and asking a lot of questions.

Even The Oregonian's own reporters on the case joined in the Stanford-bashing. Phil Manzano and John Snell wrote an op-ed piece that appeared on July 21, 1991, complaining that "based on the flimsiest of evidence, and frequently no evidence of all, Stanford suggested in his earliest columns that Francke was the victim of a plot by everyone from the Mexican mafia to the highest levels of state government."

The Governor even held a press conference to denounce my dad’s columns, calling them “B.S.” and “garbage.” When some random meth dealer named Frank Gable was convicted in June 1991, his reputation as a conspiracy theorist was baked in. A collection of his more popular columns came out in 1991, but by this time Phil was considered unreliable, if not a kook. On April Fool’s Day 1994, he wrote his last column for The Oregonian and a brief aside about his fixation on Francke. “A lot of people think I'm nuts on the subject,” he wrote. “I don't.”

In other cities used to this sort of thing, having a politician denounce your star columnist is a badge of honor. In Oregon, it was embarrassing. The publisher was chummy with the governor. Dad’s columns were awkward. He got the message, so he left.

To be fair, dad is a conspiracy theorist, and after a brief stop at another Portland newspaper where he continued to bang the Francke drum, he did decently in a kind of true crime where the cops were corrupt, the politicians were fatuous failsons, and the official word was just a cover story waiting to be pulled back. He wrote a book about what really happened at the Watergate Hotel. He wrote a book about an infamous lover’s lane triple murder in Portland, and without intending to found out that the people convicted could not have done it. Not only that, he made the case that a man with a hook for a hand could have done it. Yes, a man with a hook on lover’s lane, like in the urban legend. Turns out, the urban legend might have been true.

See, that’s the thing about my dad. He’s a kooky conspiracy theorist who usually turns out to be right. But for The Oregonian to admit he might be right about anything would be to raise the possibility that they ran out a pretty good writer. So while his books became local best-sellers and his appearances at Powell’s Books drew sizable crowds, The Oregonian never once reviewed a single book of his. It’s like they couldn’t admit he still existed.

Dad never let up on the Francke case. He even co-wrote a 1995 movie called Without Evidence that offered a $1 million reward for information leading to the killer’s conviction. (The movie is best-known today as the feature film debut of Angelina Jolie.) New evidence would come to light now and then, and my dad would always talk to reporters about it if he wasn’t writing himself. He had a small group of followers and a close relationship with Francke’s brother, but dad never took the hint.

Finally, in 2005 — by this time I had two sons of my own — The Oregonian had had quite enough of his tomfoolery, thank you, so they did a big investigation, reinterviewed witnesses, read, I don’t know, documents, and found that their conclusions matched the official story. Which, fine, I don’t mind reporters blowing a big story twice. It happens.

But what The Oregonian did to my father was wrong. The paper went after their former star columnist with sharp knives, writing that he was doing nothing more than “promoting the notion of a murder plot” that amounted to nothing more than a “conspiracy myth” that “sounded like a bewildering scheme.”

Far from shedding new light on the murder, the evidence shows that Francke and Stanford, now friends, have mostly recycled stale information. They have been effective in sowing doubt but not much else.

Even if they had been right about my dad being wrong, the word choice amounts to a character assassination bent on ending his professional viability. Even a friendlier article written a couple years later in a different publication carried this subheadline: “Columnist Phil Stanford is obsessed with a decade-old conspiracy theory. What if he's right?”

But The Oregonian was not right.

By 2013, Gable had exhausted all his state appeals, which meant federal court was his only way out. He convinced a federal public defender in Portland named Nell Brown to look into things. She started reinterviewing the witnesses, nearly all of whom recanted, blaming their testimony on what has been recently called “significant investigative misconduct,” which is a five-dollar way of saying a bunch of dishonest cops and prosecutors pressured them to lie. And if you’re wondering if there’s a word for people working together in secret to do something bad, there is. It’s called a conspiracy.

Brown wrote a brilliant, documented motion for Gable’s release in 2016. Dad was thrilled. Finally, someone with subpoena power had taken the case seriously — and found a lot of things that he hadn’t in the ‘90s. In talking about it, dad was ebullient. He didn’t much care that Gable’s only path to freedom was for a federal judge to find “actual innocence,” a long shot. Dad seemed to think that the facts would matter.

Turns out, they did. In 2019, a federal judge said on the one hand we’ve got no evidence that Gable did it, and on the other we’ve got lots of evidence that the prosecution withheld evidence and behaved otherwise like a Russian troll farm — spreading misinformation and sowing discord.

This was just after Serial had become a massive podcast hit in re-examining a bogus murder trial. A producer contacted my dad. Have you ever thought about turning the Francke case into a podcast? asked the producer. What’s a podcast? answered my dad. Murder in Oregon came out around the time that the judge let Gable out of prison and became a big dang deal. It was a bigger deal than Dolly Parton’s podcast.

There was a lot of press about the ruling and about the podcast, at least in Portland. Most of the publications made sure to get a quote from dad. The Oregonian, while dutifully reporting on the events, did not mention my dad. They didn’t even mention the success of the podcast.

Not content to let an innocent man go free, nor seeming particularly interested in finding out who actually killed Michael Francke, the Oregon Attorney General appealed to the 7th Circuit, which last week upheld Gable’s actual-ass innocence.

“The facts on appeal are extraordinary,” the ruling said. “In the thirty years since trial, nearly all the witnesses who incriminated Gable have recanted. In short, no reasonable juror could ignore the heavy blow to the State’s evidence given the significance of the recantations. The affidavits show how undisputed investigative misconduct paved the way for a string of criminal associates to turn on Gable to help themselves.”

Once again, most of the publications credited my dad for his advocacy. The Oregonian again treated him like a non-person.

I don’t particularly care if Neil Goldschmidt ever apologizes for insulting my dad. Dad got a measure of revenge for contributing to the reporting that led to the revelation that Goldschmidt was raping his teenage babysitter while he was mayor, a relationship The Oregonian called “an affair.”

But I do care that before it goes out of business that The Oregonian at least acknowledge that Phil Stanford was right all along. An apology for the 2005 hit job wouldn’t hurt, either.

Therese Bottomly is the editor-in-chief these days. In fact, she was there when the 2005 article was written. You can email her at tbottomly@oregonian.com if you'd like to express your thoughts on the matter. I’m sure she’d love to hear from you.

Jason Stanford is the co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Follow him on Twitter @JasStanford.

Thanks to Noom, I lost 40 pounds over 2020-21 and have kept it off since then. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works. No, this isn’t an ad. Yes, I really lost all that weight with Noom.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. Out in paperback now!

Jason,

I always believed your dad! He is nobody’s fool. He helped me investigate a solicitation charge for a Russian immigrant who barely understood English. Before he went to court before judge (current Secretary of State Ellen Rosenblume) I discussed with him what had happened.

The Russian guy said that he was driving home in SE Portland when he saw a woman motioning him into a driveway behind a building. He told me that she said, “You want a * job?” He nodded and drove in only to find that it was a prostitution sting by Portland Police.

Your dad learned from his sources that this sting had been in place for some time and that the people involved thought it was a big joke that the Russian guy was expecting a “blue” job as a worker somewhere.

I will never forget Rosenblum’s decision to convict him for soliciting prostitution. He didn’t know what a “blow job” was! It was a great shame for him and his family.

Your dad is a mensch!

Please send him my regards.

Donna

Great article about your dad reads like a real life version of Chinatown with even a rape of a minor. But real life takes longer to reach a satisfying end. I am glad your dad got to it.