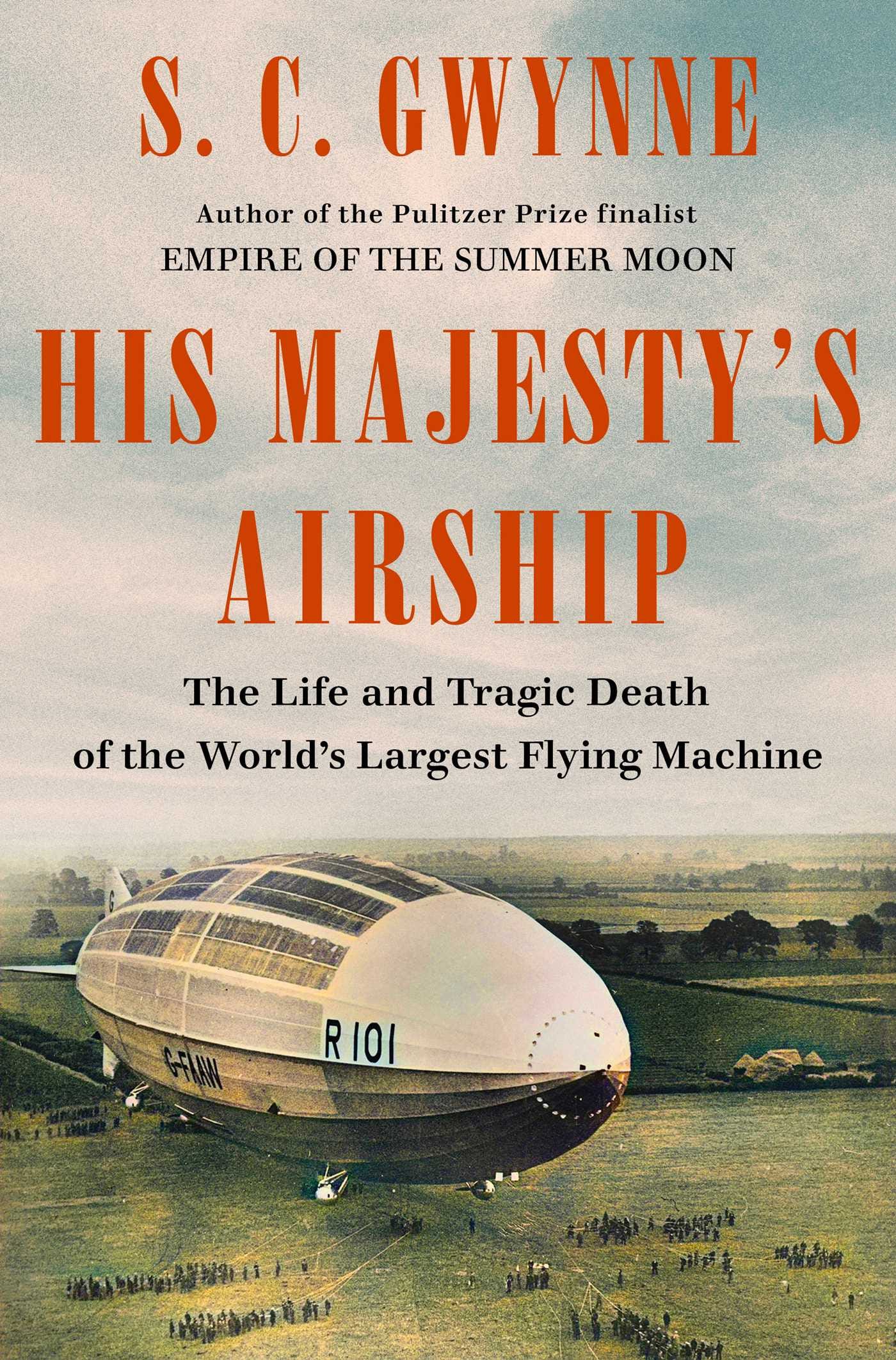

EXCERPT: S.C. Gwynne's "His Majesty's Airship"

Chapter 1: DREAMS, PIPE DREAMS, AND IMPERIAL VISIONS

If Sunday’s essay on S.C. Gwynne’s latest book didn’t make you want to buy it, and the glowing review in The New York Times didn’t either, then maybe the first chapter of Her Majesty’s Airship, exclusively excerpted here at The Experiment, will. Buy the book. It’s good time.

“Excerpted from His Majesty’s Airship by S.C. Gwynne. Copyright © 2023 by Samuel C. Gwynne. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.”

Chapter 1

DREAMS, PIPE DREAMS, AND IMPERIAL VISIONS

Our story begins in the company of the Right Honorable Christopher Birdwood Thomson, First Baron Thomson of Cardington, Privy Councillor, Commander of the British Empire, peer of the House of Lords, ex-brigadier, ex–General Staff, ex-Cheltenham, ex-Woolwich, ex–Royal Engineers, ex–a lot of other things. His official title is Secretary of State for Air, which has a nice Shakespearean ring and is an apt description of what he does for a living. He is also, according to his lengthy dossier, a talented multilinguist, a devoted Francophile, and a writer of some note. He is exceptionally tall. He has an elevated forehead, a strong Roman nose set between frank, wide-set eyes, and an understated, late-imperial mustache.

The date is October 4, 1930.

Lord Thomson is traveling this day from London to Karachi, India, by airship, a five-thousand-mile, single-stop journey over some of the earth’s most hostile terrain that no one, lord or otherwise, has ever made. The idea is a bit crazy, in the way that experimental projects often are. But relatively few people, in this time and place, appear to think so.

Thomson must first drive from his London residence to Cardington, sixty miles north of London, a place that sounds—based on his titles and honorifics—as though it might be a Renaissance country estate in rolling pastureland. Cardington is instead a gritty little industrial suburb of the small city of Bedford. Lord Thomson of Cardington has chosen it deliberately as part of his title, just as the imperial heroes Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, Lord Roberts of Kandahar, and Lord Wolseley of Tel-el-Kebir chose theirs. But instead of a battleground of empire, Thomson is lord of a sprawling manufacturing complex—the center of the exotic world of British rigid airships.

He leaves his flat in Westminster in midafternoon and travels north in his chauffeured blue Daimler with his private secretary and valet, crossing through Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly, and Regent’s Park, thence into the gray rolling countryside of Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

They stop for a cup of tea in Shefford.

Near Bedford, the Daimler climbs to the top of a hill, from which the city and its Cardington suburb are visible on the level plain below. Thomson, who has been deep in his ministerial papers during the drive, asks the driver to stop. Thomson unfolds himself from the car, all six foot five of him, in Savile Row overcoat, homburg, and neatly folded pocket handkerchief. He crosses the road and gazes over the farmland toward Cardington, where, two miles off, his eyes come to rest on an astounding sight. He has seen it before, but never from this distance, and the experience of wonder is the same every time he sees it. Secured to a 180-foot mooring mast, nose-to in a rising southerly breeze, floats the silvery form of an object larger by volume than the Titanic: His Majesty’s Airship R101—in the vernacular “R hundred an’ one.” Even from here, there is something implausible and physical-law-defying about it, a giant silver fish floating weightless in the slate-gray seas of the sky. One of the largest man-made objects on earth is lighter than the air through which it glides. The ship is flanked by two equally gigantic airship sheds, so huge they loom like medieval cathedrals over the spreading farmland.

Thomson gets back in the car, and they descend through the gathering dusk and rising wind to the Royal Airship Works in Cardington. The time is just before 6:00 p.m. The 777-foot-long, steel-framed, linen-draped, hydrogen-filled airship, with fifty-four aboard, is set to leave for India within the hour.

Despite his Cheltenham manners and ministerial calm, Christopher Birdwood Thomson is a man obsessed. He has been the driving force behind a scheme to connect the far-flung outposts of the British Empire through the new medium of the air. He has taken firm hold of the national building program whose purpose is to show the world that it can be done. Flying R101 to India will be the proof. R101 is his baby. Or perhaps more accurately, the spawn of his gauzy, rainbow-inflected vision of a future in which fleets of lighter-than-air ships float serenely through blue imperial skies, linking everything British in a new space-time continuum.

Despite his Cheltenham manners and ministerial calm, Thomson is a man obsessed.

“Travelers will journey tranquilly in air liners to the earth’s remotest parts,” Thomson has written, “visit the archipelagos in southern seas, cruise round the coasts of continents, strike inland, surmount lofty mountain ranges, and follow rivers as yet half unexplored from mouth to source. . . . They will obtain a bird’s-eye view of regions made inaccessible hitherto by deserts, jungles, swamps, and frozen wastes . . . high above the mosquitos and miasmas, and mud and dust and noise. By means of the airship man will crown his conquest of the air.”

These were extravagant promises. But in the fall of 1930, when airplanes are still uncomfortable, dangerous, and in constant need of refueling, Lord Thomson’s vision seems entirely plausible. Planes are short-hoppers, the Lindbergh miracle notwithstanding. Oceangoing ships are irremediably slow. Airships, on the other hand, can span empires, specifically the one belonging to the British, which has grown by a million square miles and 13 million souls since the end of the Great War. “I always fancied the dirigible against the aeroplane for the overhead haulage in the years to come,” wrote Rudyard Kipling, reflecting the fashionable thinking of the day. If Lord Thomson can’t bring the imperial dominions, mandates, protectorates, colonies, and territories closer in space, he can bring them closer in time, which is really the same thing. The interval required for global travel—with regular passenger and mail service—can be reduced from oceangoing weeks to airborne days.

“I always fancied the dirigible against the aeroplane for the overhead haulage in the years to come,” wrote Rudyard Kipling.

In 1927 a British air minister named Samuel Hoare flew by airplane from England to India to show how easy and practical it was. He instead proved the reverse, at least to airship promoters such as Thomson. Hoare’s 6,124-mile journey in a de Havilland Hercules trimotor required twelve bone-rattling days and twenty stops. By comparison, an ocean liner can make the passage in two weeks. R101 can do it in four days, with one stop. The king-emperor of England could be in Canada one week, Australia the next, South Africa the next. Why not?

Thomson, moreover, as secretary of state for air, is the perfect man for the job. He is a fully formed creature of empire: born of it, raised into it, a disciple of the not-quite-yet-out-of-date idea that it is the white man’s destiny to rule. He has spent large chunks of his career fighting for it in South Africa, West Africa, and the Middle East. In the coming days he will fly over parts of the empire he helped create. R101’s single stop will be in British-controlled Egypt, by the Suez Canal, lifeline of the empire. The symbolism is impossible to miss. As Thomson himself wrote in 1927, linking the empire by air “will not only confer air power, it will also consolidate the Empire, give unity to widely scattered peoples unattainable hitherto, create a new spirit or, maybe, revive an old spirit . . . and inculcate a conception of common destiny to the mission of our race.”

But even deeper purposes are working here. Thomson’s destination this day—India—is not only the shimmering jewel of the British Empire, where 150,000 Britons still rule outright over more than 300 million Indians, but also a die-hard imperialist’s idea of what twentieth-century imperialism ought to look like. India is also the place where Thomson was born. Though he left India for England as a child, he still feels India’s deep pull.

She is by design a ship of empire.

His voyage has been carefully arranged to coincide with the Imperial Conference in London—a meeting of the eight dominion premiers— where the future of the empire, and specifically the future of airships, will be discussed. Thomson’s trip is thus a piece of stage management on a global scale, a public relations stunt unseen before, even in the gaudiest days of empire. If all goes well, he will make his ten-thousand-mile round trip along the most imperial of all routes, returning to England trailing clouds of glory, having proven his theory just in time to deliver a paper on the future of airships to the conference. If he succeeds, he will be rewarded with more money and more airships and the opportunity to play out his grand vision. The newspapers have already reported rumors that the new viceroy of India will be named at the end of the conference. Thomson is the betting favorite.

Thus R101, en route to India on October 4, 1930, carries more than just her crew and cargo. She is by design a ship of empire. She has been built that way and promoted that way, and succeed or fail she bears with her the dreams not only of Christopher Birdwood Thomson but of millions of other people, too.

AT THE MAST, RAIN FALLS, the wind is rising, the air is electric. The last light is dying in the leaden sky. Cars and bicycles jam the main road. Headlamps and flashlights glow in the gathering dark. Some blink out messages to passengers and crew in Morse code. “Farewell.” “We love you.” A million people including the prince of Wales have thronged to visit the silver monster in the past month, but there has been nothing like the crowd today. Many have been drinking, and a sort of imperial delirium has settled upon the crowd. They sing the hymn of empire: “Land of Hope and Glory.” God, who made thee mighty / Make thee mightier yet. Flashbulbs pop. With great hurry and bustle the last loading is done, while men in uniform exchange greetings and goodbyes. They are all waiting on Thomson. Above them the massive ship bobs and shifts restlessly in the wind, her six acres of surface area causing her to pivot about the mast like a weather vane. More than one observer finds it strange and even unsettling to see such a gigantic piece of industrial machinery move so easily.

Many have been drinking, and a sort of imperial delirium has settled upon the crowd.

Around six fifteen the air minister’s big, boxy Daimler pushes through the traffic and up to the wooden buildings at the foot of the tower, where Thomson greets officers, crew, and fellow passengers. They represent the elite of the British airship corps, and all are going to India with Thomson. Many are legends in the service. Among them is George Herbert Scott, one of the greatest airship legends of all, the man whose 1919 voyage to New York and back in a modified Zeppelin design was the first east-west crossing of the Atlantic of any aircraft, and the first round trip. Scott, though not in formal command, will set routes and make the final decisions whether to go, based on the weather.

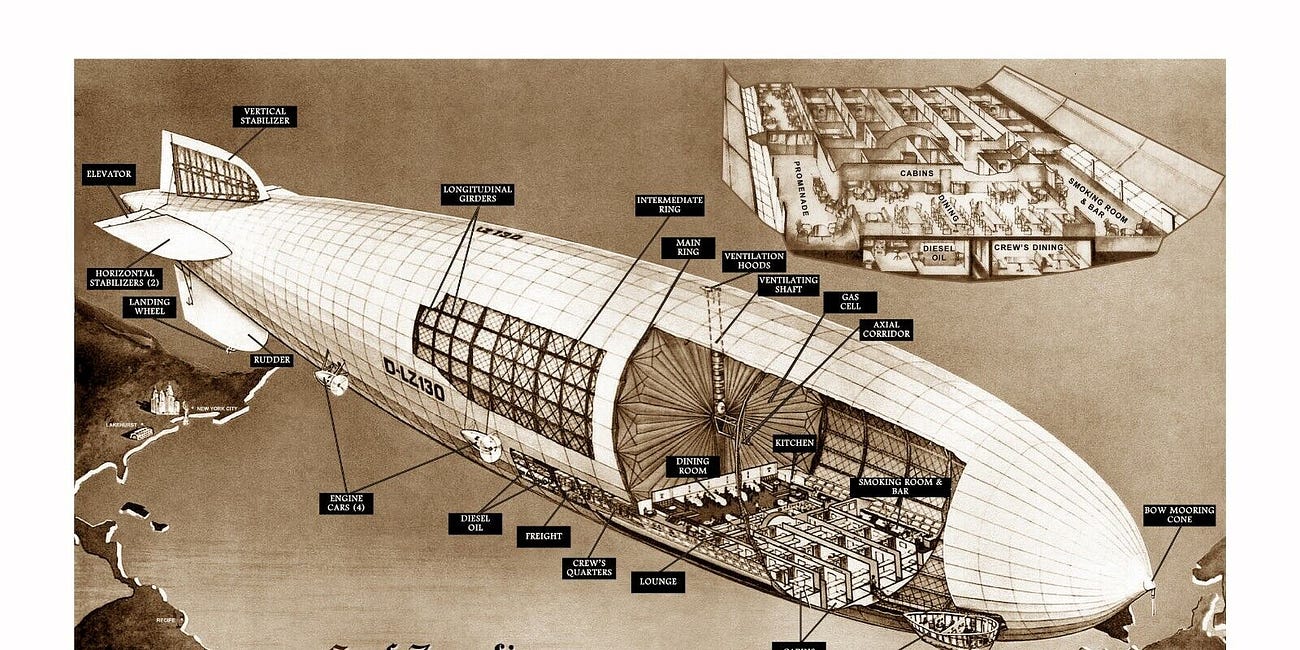

In small groups those assembled ride the elevator to the top of the mast and board through a hatch in R101’s nose, tiny figures vanishing into a cavernous space. The ship is unlike any other machine that has ever existed. She is bigger, for one thing, in both length and breadth, than anything that has flown before. Her great high-tensile-steel framework holds 5.5 million cubic feet of hydrogen gas in enormous billowing gasbags, which can lift more than 160 tons, the greatest load ever carried by any aircraft. Measured by displacement alone, R101 is nearly twice the volume of United States Lines’ SS Leviathan, the largest ocean liner in the world.

The most striking thing about the airship’s interior is its luxury. The effect is of a prewar steam yacht married to a warship’s admiral’s quarters. From her sixty-seat art deco dining room, trimmed in white, gold, and Cambridge blue, to her commodious lounge with its windowed promenades, she is meant to suggest the grand ocean liners of the day. She even features, in the midst of so much explosive hydrogen, a smoking room. But the opulence is all surface: in an airship where weight saving is everything, there is none of the heavy-oak-and-marble solidity of a Pullman car or a steamship. The gold-trimmed pillars are not pillars; they are illusions created by ultralight aluminum alloy, balsa, linen, and paint. Walls and ceilings are paper-thin. Like the ship’s outer skin, which is nothing but a fragile layer of linen treated with “dope”— celluloid varnish meant to maintain tautness and keep water out—and stretched over light steel girders, the entire structure has the feel of a giant Chinese lantern. The less the weight in the frame, the more cargo that can be lifted.

The effect is of a prewar steam yacht married to a warship’s admiral’s quarters.

Which does not mean, R101’s hyperkinetic press office is keen to remind the world, that the ship is not safe. R101 is all about safety, the office insists. Safety first, safety last, safety deliberately overengineered, safety based on hard-won lessons of the past, safety rooted in technical wizardry. The safest aircraft of any kind ever built. She runs on heavy-oil diesel engines, which have never before been deployed on an airplane or airship, and whose fuel is extremely difficult to ignite. Fires are bad in any aircraft, but measurably worse in hydrogen-filled airships and still worse in hot, tropical climates, where R101 is headed. The Beardmore Tornado diesels are much heavier than gas engines, but Great Britain is taking no chances. R101 is said to be virtually flameproof. Her metal structure is so much stronger than it needs to be—R101’s engineers used a 1921 British airship crash as a model of what not to do, then doubled down—that it is said to be unbreakable. Her unique gas valves allow precise altitude control even in stormy weather. Her final, seventeen- hour trial flight was flawless. “ ‘Safety first’ may not be a very paying proposition in regard to politics,” Thomson told the House of Lords, “but I am sure it is the right thing in regard to airships.” A prominent German airship engineer has called R101 “the safest conveyance on land or sea or in the air that human ingenuity has yet devised. . . . She is a great, strong thing.” Part of this is pressroom hyperbole, of course. But Thomson and the men who designed and built his airship believe it. They are thus proposing a revolutionary change in the nature of air travel. The early twentieth century has seen more gruesome crashes, of both airplanes and airships, than anyone cares to remember. Forgetting just how dangerous flying is is critical to the industry’s progress. Pilots and passengers who think they are likely to die are unlikely to fly. But those who do fly still die in large numbers. In 1929, the most lethal year on record, there were fifty-one commercial-airliner crashes with fatalities. The 1920s saw several infamous examples of rigid airships plunging to earth. R101 will show that the dignified flight of an ultrasafe airship—serene, low- speed cruising above the land, with passengers waving to people on the ground and watching deer run through forests—is the future of long-distance travel.

“the safest conveyance on land or sea or in the air that human ingenuity has yet devised”

The loading continues.

There are a few odd moments. As George Herbert Scott waits for Thomson to arrive, two stewards walk by carrying tins of biscuits. Scott, who has been frantically trying for the last few days to lighten the ship, which has for the first time been simultaneously inflated to its maximum limit and loaded to its full design capacity of 160 tons, orders the men to throw away the tins and save the biscuits in paper bags.

Which might seem like prudent, if slightly over fastidious, weight management.

Then, to everyone’s astonishment and dismay, the great Lord Thom- son’s baggage arrives. He has already insisted on dressing up the lounge and entranceway with an expensive, heavy 2,630-square-foot Axminster carpet, weighing over a thousand pounds. Now come his effects: two large cabin trunks, as though he were leaving for several months instead of two weeks; four suitcases, with his ministerial papers included; two cases of champagne for his state dinner in Egypt; and, finally, a rolled-up ten-foot-long Sulaimaniya carpet from Kurdistan, which requires two men to carry it and does not fit in the lift. The total weight of just his personal luggage is 254 pounds, compared to 350 pounds for the entire crew of thirty-five. It seems impossible that Thomson doesn’t understand about weight in airships.

AT 6:36 P.M. R101 slips her mooring and swings free. A cheer rises from the crowd. Normally the ship moves upward and away from the mast. But now, suddenly, she lurches earthward. Such a movement by something 777 feet long and 130 feet wide is something to see. It arrests the attention. To stop the fall, Captain Carmichael “Bird” Irwin releases a massive amount of water ballast—four-plus tons of it, almost half the ship’s total—which pours from the bow in a great waterfall, drawing an even louder cheer from the onlookers, who are not quite sure what they are seeing. The ship responds, the nose buoys up. R101 slides away from the mast, her control car glowing white and her running lights, port and starboard, winking red and green. Her five Beardmore Tornado diesels throb and thrum into the nearly complete darkness.

“But not, I hope, with undue risk to human lives.”

As she moves off, watchers on the ground can see Lord Thomson himself, flanked by Sir Sefton Brancker, Great Britain’s director of civil aviation, leaning on the promenade rail, illuminated from behind by the bright windows of the saloon. One eyewitness will recall that the two men, and other passengers, too, appeared “starkly clear.” Six weeks before, Thomson wrote to his girlfriend, a Romanian princess named Marthe Bibesco—who looms large in the narrative of his life—to tell her how thrilled he was about his upcoming trip to India. In the letter he expressed his keen desire to experience bad weather while flying in an airship, something he had never done: “To ride the storm has always been my ambition, and who knows but we may realize it on the way to India.” Then he added, “But not, I hope, with undue risk to human lives.” That was a bit like saying, “Damn the torpedoes, as long as no one gets hurt.” It seemed an odd and almost naïve thing to say, as though he were not about to make the most perilous journey in the short history of aviation.

S.C. Gwynne is the author of Hymns of the Republic and the New York Times bestsellers Rebel Yell and Empire of the Summer Moon, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He spent most of his career as a journalist, including stints with Time as bureau chief, national correspondent, and senior editor, and with Texas Monthly as executive editor. He lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife, who is awesome.

Further Reading

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!