Charlie Bonner is nervous for me to tell you this story. He asked when I intended to publish it, texting, “I need to fortify my brain.” Honestly, there’s nothing that follows that is explicit. It’s all very PG-13, but it’s about an aspect of what it means to live as a young, single, gay, and sexually active man in Texas right now. See, I lost some of you with that last adjective, didn’t I?

Charlie gets it. “People were much more comfortable with the idea of someone being gay in the, like, pride-rainbow sense, and very uncomfortable when they heard the rumors around me having sex in high school,” he says.

But before you bail on Charlie’s story, know we’re not going to be talking about men having sex with each other as much as we are going to have to accept from jump that Charlie, as has been legal in America since 2003 when the Supreme Court ruled in Lawrence v. Texas, has sex. That’s all you have to do to understand a story about what happens when a government has a hard time with exactly that. Yes, sex is not all of what being queer is about. It’s about marriage and family and leading an impromptu singalong at a luncheon in a Julia Roberts rom-com and Pete Buttigieg and your aunt’s roommate. But it’s also sex, which as Charlie says, can make people uncomfortable.

If you’re still with us, we can move along, but I wanted you to know what you were getting into, because Charlie sure didn’t know.

That’s Charlie. He was a high school junior in Richmond, Virginia and still in the closet to his family and most of his friends, including his best friend Gabby. He ran with what he calls a “very community service-minded” crowd that thought donating blood was cool. One Spring weekend, Gabby convinced him to go to a blood drive at an American Family Fitness in town. Charlie figured he could potentially save people’s lives without costing him anything, and besides, he’d get a cookie.

As he was filling out his health screener, he got to the question about whether he’d ever had sex with another man. As it happens, he’d had sex for the first time a couple months prior, a fact he had not shared with his best friend or, for that matter, everyone else at the gym that morning.

“I was like definitely looking over my shoulder,” remembers Charlie, who had no idea he was going to have to answer questions about his sexual history. “I did not want to deal with whatever situation could occur at the American Family Fitness. I was like, oh my God, like what am I even doing here? But I did it, and I decided in that moment the right thing to do was to answer honestly.”

“I decided in that moment the right thing to do was to answer honestly.”

A nurse took him aside to go over his screener. When they got to the sexual history question, she explained that they couldn’t take his blood, but he could still have a cookie. “And that is how I found out about the FDA guidelines around gay people donating blood,” he says.

In response to the AIDS epidemic in the ‘80s, the FDA imposed a lifetime ban on blood donations from any man who had ever had sex with another dude. By the time Charlie was in high school, the American Medical Association said that screening processes had improved enough to make the ban meaningless, and gay rights groups had long opposed the ban as discriminatory.

But to little Charlie, none of that mattered. He was just a kid and already feeling shame about being gay. “And then this was a whole new shame,” he remembers. “It made me feel dirty, you know, like there was something wrong with me. They were rejecting my blood, you know, something that they were taking from all of these other random people in high school. All these other random, 16-year-old, run-of-mill people. But like my blood had something so wrong with it they couldn't even accept it, you know, like that was instantly already on top of all the shame around my identity and around coming out. It was horrible. It was awful.”

“It made me feel dirty, you know, like there was something wrong with me.”

Gabby was already in the chair giving blood. Charlie told her they couldn’t take his blood because his iron level was low and peaced out. “I was like, I’m not coming out to Gabby like this. I’m not doing this today. It was so horribly embarrassing to me even though they did it in private,” he says. “Yeah, I totally lied to her. I don’t know if I ever updated her on that. I did not have low iron that day. I never really told her that.”

In 2015, the FDA changed their rules to allow donations from men who had abstained from sex with men for 12 months. By then Charlie was in college in Austin, and let’s just say he did not meet the criteria. He had a lot going on with his political organizing, campus life, and studies, but no, Charlie did not hit a year-long dry spell in college, nor should he be expected to. It’s college, and Charlie, well let’s just say he’s not shy, and it’s nearly impossible to not enjoy his company. He’s a popular kid.

Then Charlie graduated, and the pandemic hit. Blood supplies were running low, so in 2020 the FDA shortened the required period of abstinence for men having sex with other men to three months.

Mind you, and by now I’m sure you’re wondering, this rule didn’t apply to straight people or for that matter to lesbians. As the Human Rights Campaign recently pointed out, a woman could have unprotected sex with as many partners as she wanted without knowing anything of their sexual histories and still donate blood regularly. But a dude has sex with one dude — and get this, it applies to oral sex, too, even if it’s protected — and suddenly they won’t take your blood unless you’ve been keeping to yourself for three months.

“Unfortunately, I qualified. Not my own choice, life’s choice.”

And because of the self-imposed isolation of those who treated COVID-19 like the deadly airborne plague that it was, Charlie finally qualified. “It was a different time,” he says. “Unfortunately, I qualified. Not my own choice, life’s choice.”

He was walking down the street one day and saw Austin’s blood bank’s distinctive sky blue and Creamsicle orange bus doing a pop-up blood drive. This time, because the rule change had recently made the news, Charlie knew that he qualified. “I was like, wow, I should finally do this. Right? Like, this is something that has kind of haunted me for several years,” he says.

But Austin hadn’t updated their local rules to reflect the new national guidelines, and once again, Charlie’s blood was refused, and he went into the system as being rejected. “I’m like, what the…? It took decades of advocacy to get the federal guidelines to change. And then the actual personal experience is still the same, you know?” he says. “It really was so disappointing and still, I think there was a lot of shame in it.”

“This is something that has kind of haunted me for several years.”

In Texas, hell or high water is the actual weather forecast, so it could have been Ice Storm Uri, a tornado, or any one of a record number of school shootings that year, but for reasons forgotten to Charlie there was a blood drive on the capitol grounds in 2021.

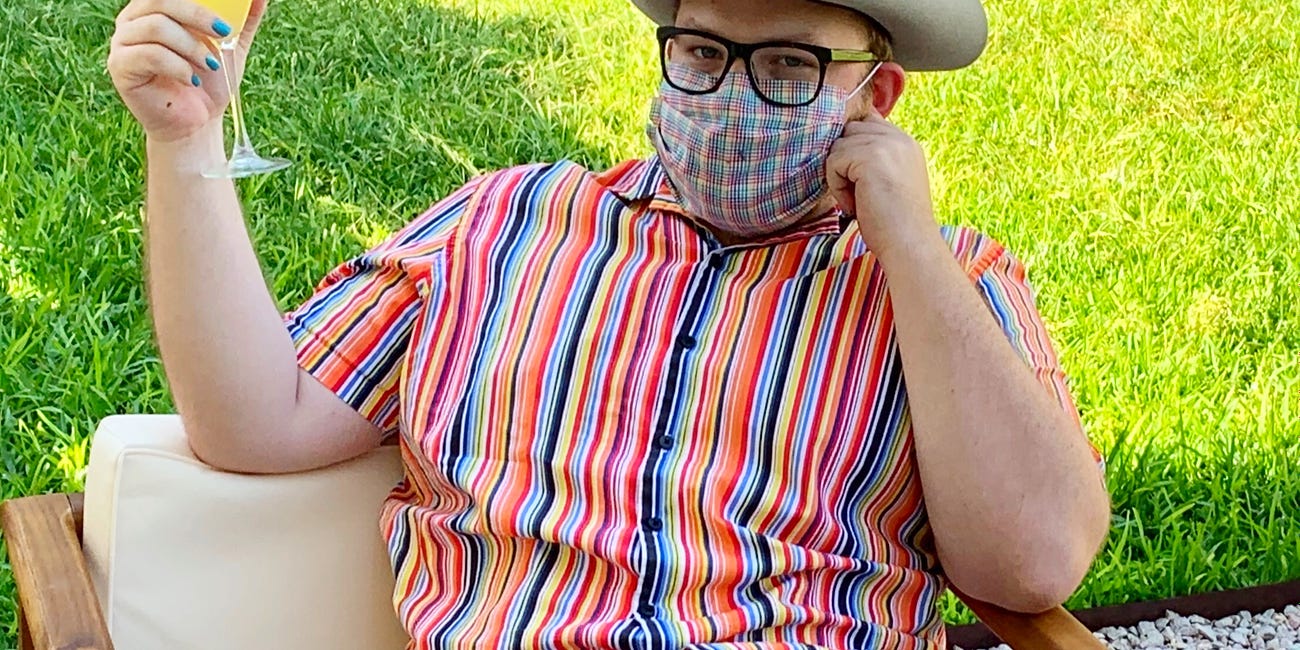

And unlike at the American Family Fitness, everybody knew him at the capitol. By then a well-known political activist focused on the youth vote and voting rights, Charlie had grown out of his safe-for-Netflix rom-com aesthetic and adopted a look he called “yee-haw gay.” Put simply, Charlie did not go quietly into that good fight. The only time Charlie Bonner was straight passing was when he walked straight pass one. Among the dark suits and dress boots of the capitol lobbyists and the oxford shirts and khakis of the legislative staffers, Charlie Bonner was easier to spot than Waldo.

He wasn’t about to stand in line for a couple hours only to be turned away in such a conspicuous setting in front of scores of colleagues. He asked to speak to someone in charge and found out that that he was still marked in the system as having rejected blood. Strike three, he’s out.

Among the dark suits and dress boots of the capitol lobbyists and the oxford shirts and khakis of the legislative staffers, Charlie Bonner was easier to spot than Waldo.

In June, the FDA changed the rules yet again. You might have seen this in the news portrayed as a relaxation of the rules against gay and bisexual men donating blood. Now, instead of just men, they ask everyone about what they’ve been doing with other people. If you’ve been celibate or monogamous* for three months, cool, right this way, you literally get a cookie.

But if you’ve had new or multiple partners in the last three months, no soup for you. You’re also rejected if you’ve had anal sex*, which many men reportedly enjoy with other men. So gay men can totally give blood, unless and in case they are having the kind of sex many gay men like, even if they are monogamous and married and otherwise living Williams-Sonoma lives that would not make you even slightly uncomfortable.

None of that matters to Charlie, because he doesn’t qualify for a completely different reason: He’s taking PrEP, which prevents you from getting infected by HIV. You heard that right: A screening process to prevent HIV from entering the blood supply eliminates donations from men who take medicine that prevents them from getting HIV. It seems cruelly absurd, though apparently some scientists worry that PrEP could confuse the screening process and cause a false negative. “Basically the science is murky,” says Charlie, “but everyone I know is on PrEP.”

“What gets written down should be true.”

Though if Charlie’s taking PrEP, that means he’s HIV negative. His blood should be good to go. Why not just lie?

“Well, one, I don’t think it’s good to lie on health or government records,” says Charlie, who also knows that lying about yourself has a way of coming back around on a fella in politics. “What gets written down should be true. You know?”

But there’s something more personal to Charlie about answering that question. From that very first time, what he did with his body was enmeshed with his identity, and to lie about what he did would be to deny who he was. “I was like, how dare you ask me to lie about my identity, my life,” he says. “That's something that's very important to me, you know? We don't ask other people to do that.”

Charlie spent the better part of the year manning the barricades against a legislative onslaught against his community. Every time lawmakers debated criminalizing drag shows on the false pretext that they sexualized children, Charlie was there, coaching a drag queen pal through her testimony. When an anti-trans bills popped up, Charlie was there at the mic, telling a largely unhearing world that the biggest threat involving trans people is that they will get beat up or end their own lives because society shows them almost nothing but hate and disgust.

“How dare you ask me to lie about my identity.”

Charlie’s brand of activism is public advocacy, and when his friends were getting attacked, Charlie ended up becoming a public face of those being called sexual deviants. Friends he brought to the capitol to testify were roughed up and arrested by state troopers. Others he trained to advocate at the capitol were doxxed. It took a toll on him. Charlie has an electrically sunny personality, but as he told me about this, he began, much to his surprise, to cry.

“Oh my God. Every day. Okay. I was called a groomer every day on the internet for four months. So much to the point that it kind of didn’t make me wanna be around kids. Like, I didn't want somebody to have ammo to take a photo of me with my nail polish next to a kid and be like, ‘F**king groomer, we told you.’ And for nothing because I support people on the internet.”

The attacks made Charlie question the way he presents himself. Should he stop painting his nails in professional settings? He’d ask himself, Can I wear that? Is this too much? The ordeal — and therapy — helped Charlie see the boxes that the culture had tried to put him in his whole life. If you know Charlie at all, and by now you do, you know which way Charlie went at the intersection of Tone It Down and IDGAF.

“I was called a groomer every day on the internet for four months.”

“Thankfully, the voice that has won out is that the only answer is to advocate more and to be queerer in public, to really go for it. Right? They're already thinking I’m absolutely the worst version of a human being I could be. Why should I be limited by them at all in whatever boxes they put around me. I am done with it, and I’m doing whatever I want now,” he says. “I think that the past couple months have just really revealed to me in which the ways those boxes are suffocating me. The box itself is a threat to my existence. And I’m not… I can't play by those rules anymore.”

When Charlie had told me about his failed attempts to do something as basic as donating blood, I’d understood his story only superficially. I thought it was about bureaucratic follies and grumpy, scientifically obsolete oppression.

And I confess that when I saw the headlines this summer about the FDA’s change in the donation rules, I was hoping I could tell his story with a happy ending. Maybe I could even drive down to Austin. I could pull up to the condo on South Congress where he’s squatting, honk, and say, “Get in loser, we’re going blood donating.” Charlie would smile and laugh and probably be wearing a kaftan. He’d narrate his nerves while they put the needle in his arm, and afterwards we’d get loopy at brunch while we talked about people we hated.

Yes, I put Charlie in the gay best friend box.

I much prefer this Charlie. The world tells him to get back in the box or he’ll be digitally stoned and pilloried as a sexual deviant, and his answer is to be more Charlie. This Charlie knows that you’d be thrilled if he found a fella, got married, and moved next door, as long as he didn’t dress so, well, you know. But society has rejected his blood as unfit to be mixed with the rest of ours. Our rules do not include him, so he’s going to go ahead and ignore our rules for now, thank you. Yes, I do think I prefer this Charlie.

Jason Stanford is a co-author of NYT-best selling Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. His bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, Time, and Texas Monthly, among others. Email him at jason31170@gmail.com.

Further Reading

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is how I have fun.

Buy the book Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick banned from the Bullock Texas History Museum: Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself is out from Penguin Random House. The New York Times bestseller is 44% off and the same price as a paperback now!