Be Curious

Opinions are nothing like you-know-what because you actually need that

Welcome to The Experiment, where we’re celebrating Mother’s Day by trying to be curious, not judgmental, and Jack Hughes finds a lesson for Liz Cheney in what Gerald Ford went through in 1976, which has nothing whatsoever to do with Mother’s Day.

As always, we offer recommendations on what to do (not pursue happiness), read (Aunt Gigi dropping knowledge on poetry), watch (Exterminate the Brutes), and listen to (“Cosmosis” by Tony Allen).

But first, you know what’s wrong with what we say about opinions?

We’ve all heard it, and most of us have said it. “Opinions are like a**holes,” we say. “Everybody’s got one.” We say this when someone lets rip an odious take about what women are wearing or how freedom of speech means you shouldn’t face consequences for what comes out of your own damn mouth, or pretty much anything any pundit says about Colin Kaepernick. It’s a rhetorical shrug emoji. What’re ya gonna do? we’re saying. Even idiots are entitled to their own opinions.

The problem with metaphors is they give literal shape to our thoughts, and yes, I literally mean literal. Before, there is an abstract idea, and because our dumb brains need all manner of mollycoddling, we, the fumbling meat sacks entrusted to care for our brains like high school sophomores tending to eggs for a week in health class, draw pictorial representations in our minds to help our brains make sense of a complicated idea that opinions are common, ephemeral, and not necessarily deserving of our consideration. With one simple picture, we cook that metaphysical idea down to a reduction in which opinions are common and often full of sh*t.

Yes, your brain is partly a 13-year-old.

As annoying as it might be to accept that one of the officers on the bridge of the U.S.S. Your Brain could be Beavis or Butt-head, that’s not what I take issue with. What’s wrong with the metaphor is the 1:1 ratio and the declaration that “everybody has one.” I have so many — opinions, that is. I have so many that I constantly walk around in a guarded state of self-censorship. This week I did not compliment a co-worker’s blouse even though she looked especially awesome. I did not tell a friend that he was being self-centered because, admittedly, I was fighting with him in my head. I did not tell anyone about any number of things, because I’ve learned that my opinion does not matter to the things. A song does not care if I like it.

When I did offer my opinion last week, I invariably made things worse. I’m not talking about being at work and someone presents you with a problem and asks your opinion. I’m talking about coming upon a problem, pointing a finger, and declaring, “That is wrong.” Well, no kidding. Whoop. See also: Di and Do. Sometimes the problem would have resolved itself had I shut the heck up. Sometimes I should have asked my three favorite questions: what? why? and what if?

A song does not care if I like it.

Opinions rush me to judgment. My favorite scene in Ted Lasso is, to me, about masculinity. Actually, that episode, the “Diamond Dogs,” has several scenes where men struggle with ill-fitting personae and try to honestly deal with their feelings to forge better relationships with each other and with women. There’s even a quick, subversively tender scene where players discover their kit man, Nathan, asleep in the cargo hold of their bus. “Mon cher,” coos the Canadian goalie in a simple act of acknowledgement of fraternal affection. That was a smart thing the writers slipped out of the actor’s mouth. He never would have said that in the locker room or when Nate was fully awake and not about to vomit.

This is also the episode where the Diamond Dogs, Ted’s personal male detoxification squad, uses the metaphor of scissors to get Ted to cut himself some slack and compares Roy Kent and Keeley to cookies and cream.

”And I think we all agree, two great tastes that go great together, right?” asks Ted.

“Perfect analogy,” notes one of men.

There are metaphors all over this mess because this episode gets messy. It asks the basic question that bedeviled me for decades: What do I do with my baby bunny feelings, which is what I called my gnawing feelings of inadequacy. Following that question is its toxic corollary: If those feelings are valid — and why wouldn’t they be? I’m having them, and this is me we’re talking about — shouldn’t my life be focused on addressing those feelings?

The Diamond Dogs have spoken on this matter, and I refer you to episode 8 if you haven’t seen it. [And dear lord in a merciful heaven if you have not gotten Apple TV+Max or whatever it’s called. If you pay for Apple TV and don’t like Ted Lasso, I’ll reimburse you for a month.] If I asked any Ted Lasso fan about toxic masculinity and the “Diamond Dogs” episode, they’d focus on the perfect little story arch that begins with Ted’s crisis, the formation of the Diamond Dogs, Roy finding out that Keeley slept with Jamie Tart (“The prince prick of all pricks,” says Roy), the reunion of the Diamond Dogs to deal with Roy’s reaction to that news, and then Roy dealing with this feelings like a dang grown up in his rapprochement with Keeley.

Whoop. See also: Di and Do.

The scene I’m thinking of, though, is the scene most argued about in the series, the dart scene. Jason Sudeikis’ eponymous character makes a bet with his boss’ ex-husband, the billionaire Rupert. He bought a minority stake in the team just for the right to sit in the owner’s box and criticize his ex-wife Rebecca Welton to the press, which in London is tantamount to emotional torture. He delivers this threat with an oily smile. He’s used to getting what he wants. He doesn’t have the team anymore — she got it in the divorce — and he wants to hurt her, publicly, in a way he is now legally entitled to do.

This scene is set up earlier in the episode with a conversation in which Ted acknowledges that he owes a debt of emotional labor to Rebecca, and if you didn’t get that the ur-text of “Diamond Dogs” was metaphors, feast your peepers on this dialogue:

“Think of me as your own personal metaphorical Saint Bernard,” Ted tells his boss, Rebecca. “You don't need to be dealing with a metaphorical avalanche to avail yourself to the metaphorical bourbon hanging around my neck. Metaphorically speaking. Okay?”

Flash forward to the pub, where Rupert challenges Ted to a game of darts. If Rupert wins, he can pick the starting lineup for the last two games. If Ted wins, Rupert can never go to a game, much less to the owner’s box, for as long as Rebecca controls the team.

“What are you doing?” whispers Rebecca.

“I believe some folks call it white knighting,” admits Ted, “but I’m just going with my gut here.

Does being a man mean being able to buy whatever you want and to win friends and influence people? Does it mean being so rich and powerful you can do whatever you want to whomever you choose?

Or does being a man mean accepting that abusive criticism is about the critics and not you, that your hurt feelings do not justify hurting others, or that whether or not someone respects you is not nearly as important as whether you, like ghosts, believe in yourself. This is Ted Lasso, and he is more interested in how his behavior affects those around him than whether those around him hurt his baby bunny feelings.

Ted is on the ropes at the game’s close, and Rupert is peacocking about what he’ll do to fix the team.

“Now, now, it's not all Ted's fault,” he tells one of the bar patrons. “My ex-wife's the one who brought the hillbilly to our shores. I know she's always been a bit randy, but I never thought she would fuck over an entire team.”

“Hey!” says Ted. “Better manners when I'm holding a dart.”

He needs more than a smart rejoinder to beat Rupert. He needs two triple 20s and a bullseye. But Ted, undeterred, starts telling a story about how “guys have

underestimated me my entire life.” Then one day he noticed a Walt Whitman quote on a schoolhouse: “Be curious, not judgmental.” He realized that people who underestimated him — *cough* Rupert *cough* — were judgmental and not curious.

“'Cause if they were curious, they would've asked questions,” he went on. “You know, questions like, ‘Have you played a lot of darts, Ted?’”

Turns out, he explains as he hits one triple 20 and then another, he has played a lot of darts, every Sunday growing up with his father. Then he calms himself with mantra of the name of the thing that makes everything better: barbecue sauce.

Bullseye.

See? Metaphor.

I used to think my opinions defined me. I had strong opinions about men’s fashion, sexual mores, and pedagogy. At one point I openly pined for a career in punditry, which is just getting paid for your opinions. As a syndicated columnist, I gave my opinions away for free, never recognizing this as evidence of their worth. I even had opinions about opinions. I could and may still go on for hours about the demonstrable wrongness of others. That phase of my life reminds me of reading Dr. Seuss to my children. Full of lovely nonsense, a fond memory best kept in the past.

Opinions are too often judgments. This is how I understand Jesus’ “Judge not, lest ye be judged,” or Seneca’s “You look at the pimples of others when you yourselves are covered with a mass of sores.”

As we’ve seen a lot lately, opinions are immune to facts. They blind us to reality by making us incurious about what we don’t know. Opinions focus our minds on our judgments of others, which are seldom useful, or on ourselves, which are sometimes unproductive and unkind. And even though we walk around in an odd expectation that people want to know what we think, opinions are completely optional. I don’t need to have an opinion on most things.

In short, opinions are nothing at all like a**holes. You actually need one of those.

The Spirit of ‘76

by Jack Hughes

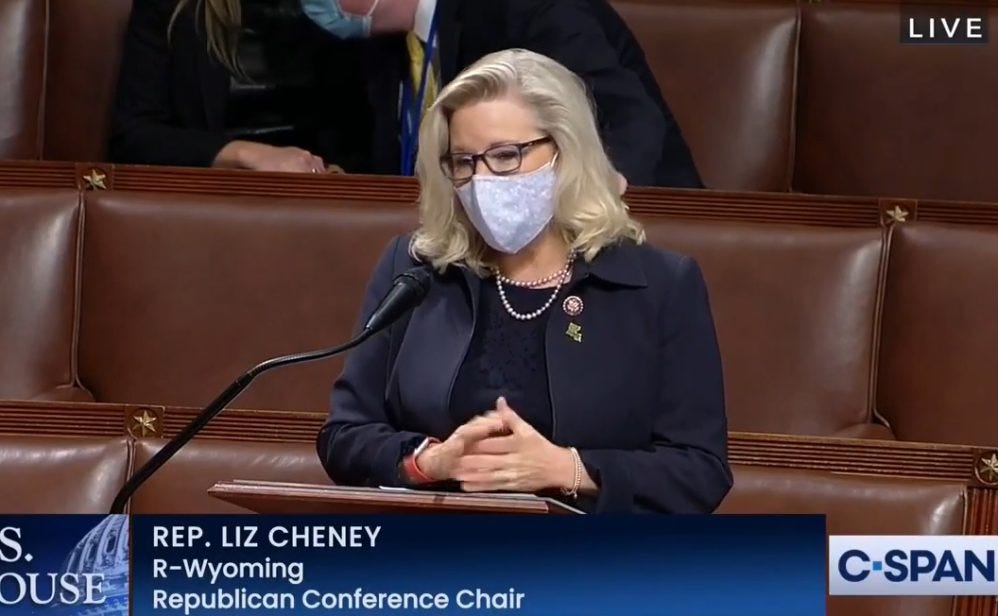

Jack Hughes finds historical parallels between what Liz Cheney is enduring right now and what Gerald Ford went through in 1976. Neither of them set out for the White House, but that’s where Ford ended up and where Cheney might be going next.

How we’re getting through this

Making Disney anti-racist

Exploring solutions journalism

Incorporating audio into newsrooms

Baking Ted Lasso’s shortbread biscuits

What I’m reading

Jim Arvantes: “Tuesday Talks: Award-Winning Poet Captures Ineffable Qualities of Poems and Poetry” - This is my aunt!

“In times of stress, we turn to poetry because we don’t have an easy explanation and poems can help with the lack of ready answers,” explained Bradford…

Alex Curry: “People pay for news that reinforces their social identities” - What makes people pay for news when information is free?

…when Chen and Thorson asked participants if they consumed news to fit in socially, they found that this motivation — related to a person’s social identity — was tied to the desire to pay for news.

Laura Meckler and Hannah Natanson: “As schools expand racial equity work, conservatives see a new threat in critical race theory” - When it comes to schools, politicians can get very dumb.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) called for $17 million to fund curriculums that exclude “unsanctioned narratives like critical race theory.” In North Carolina, Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson (R) established a task force to eradicate “indoctrination in the classroom” after the state adopted new social-studies standards that focus on marginalized groups. The opposition filtered down to Moore County, where school board member Robert Levy is trying to hold up the new curriculum over concerns that critical race theory will infiltrate the district’s work. A Republican gubernatorial candidate in Virginia posted an education plan, and two of the seven points were devoted to combating critical race theory.

Reese Oxner: “White Republicans are refusing to get the COVID-19 vaccine more than any other demographic group in Texas” - Jesus wept.

In Texas, 61% of white Republicans, and 59% of all Republicans regardless of race, either said they are reluctant to get the vaccine or would refuse it outright, according to the February University of Texas/Texas Tribune Poll.

What I’m watching

I’m not exactly sure what I saw, but I watched all the episodes of Exterminate all the Brutes, a four part so-called “hybrid docuseries.” Says director Raoul Peck, "I wanted to push the boundaries of conventional documentary filmmaking and find a freedom to tell this story by any means necessary." He certainly did that.

What I’m listening to

Tony Allen, the venerable Afro-beat drummer, was working on a hip-hop album when he died. A year later, that album, There Is No End, dropped, and it left a mark. It’s an evolution of jazz and hip-flop.

What do you think of today's email? I'd love to hear your thoughts, questions and feedback. I might even put ‘em in the newsletter if I don’t steal it outright.

Enjoying this newsletter? Forward to a friend! They can sign up here. Unless of course you were forwarded this email, in which case you should…

Swimsuit season’s coming. Try Noom, and you’ll quickly learn how to change your behavior and relationship with food. This app has changed my life. Click on the blue box to get 20% off. Seriously, this works.

We set up a merch table in the back where you can get T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tote bags now. Show the world that you’re part of The Experiment.

We’ve also got a tip jar, and I promise to waste every cent you give me on having fun, because writing this newsletter for you is some

Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of the American Myth by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and myself comes out June 8 from Penguin Random House. There is no better way to support this book than to pre-order a copy. You’re going to love reading what really happened at the Alamo, why the heroic myth was created, and the real story behind the headlines about how we’re all still fighting about it today.